The forward-thinking architect who helped rebuild Manchester after the Blitz

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 6 months ago

- Art & Design, City of Manchester, Featured, History, People

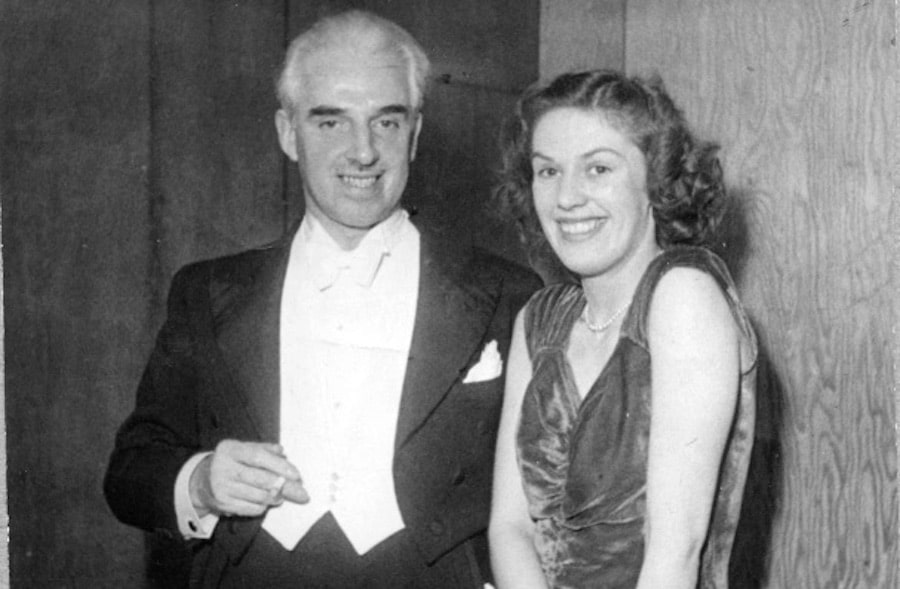

Leonard Cecil Howitt was one of Manchester’s most influential city architects.

His architectural legacy continues to be felt in Manchester to this day.

Born on December 27th, 1896, in Islington, London, Howitt left a huge mark on Manchester through his innovative designs and dedication to public service.

Howitt’s tenure as Manchester City Council’s chief architect from 1946 to 1961 was marked by a commitment to Modernist principles, and he oversaw the creation and restoration of some of the city’s most iconic structures, including the rebuilding of the Free Trade Hall after a WW2 bombing, Hollings College (affectionately called the Toast Rack), and the Courts of Justice.

His work reflected the post-war optimism of his time, combining functionality with a distinctive aesthetic flair that still resonates in Manchester today.

Early Life and Career

Leonard Howitt was born into a working-class family.

His father, William Howitt, was a type founder, but after William’s death around 1910, Howitt and his mother, Ada, moved to Manchester.

Initially, Howitt began his career in architecture with an apprenticeship at Manchester Town Hall.

However, his ambitions were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War, during which he served in the army.

After the war, Howitt pursued his passion for architecture at the University of Liverpool, graduating in 1925. He then worked for Herbert J. Rowse in Liverpool, where he contributed to projects like the Mersey Tunnel ventilation towers.

In 1937, Howitt returned to Manchester as Deputy City Architect, just before the outbreak of the Second World War.

His second period of military service saw him rise to the rank of major, after which he resumed his role in Manchester.

By 1945, he was acting City Architect, and in 1946, he formally assumed the role that would define his career.

Post-War Reconstruction of Manchester and Iconic Projects

The post-war period in Manchester was one of both devastation and opportunity.

The city had suffered extensive damage during the Manchester Blitz, leaving a scarred urban landscape in need of renewal.

Howitt embraced the challenge of rebuilding, and his designs embodied a blend of Modernist principles with a sensitivity to Manchester’s industrial heritage. An interesting blend, and not to everyone’s taste.

Rebuilding Manchester’s Free Trade Hall

One of Howitt’s first major projects was the restoration of the Free Trade Hall, a symbol of Manchester’s civic pride and political heritage. Originally constructed in 1853, the hall stood on the site of the infamous Peterloo Massacre, where in 1819, a cavalry charge on protesters demanding parliamentary reform resulted in numerous deaths and injuries. The hall itself had suffered significant damage during the Blitz.

Howitt’s restoration work on the Free Trade Hall was not merely about rebuilding; it was about breathing new life into a Manchester landmark. The restored hall reopened in 1951, with a ceremony attended by Queen Elizabeth II.

Howitt’s design transformed it into a grand concert venue that would host iconic performances by artists such as Bob Dylan, Pink Floyd, and the Sex Pistols, cementing its place in popular culture.

Bob Dylan was famously called Judas my a rowdy Manc crowd, after his transition to playing rock and roll based music, a huge divergence from folk at the time – leading to one of the most iconic performances in music history.

Today, the building stands as a hotel, but its historic façade and interior nod to Howitt’s meticulous and respectful restoration work.

Hollings College: The Toast Rack

Perhaps Howitt’s most distinctive and beloved creation is the Toast Rack building, officially known as Hollings College.

Completed in 1960, this Modernist structure was designed to house the Domestic Trades College and later became part of Manchester Polytechnic, now Manchester Metropolitan University.

Its unusual hyperbolic paraboloid frame and series of arches give it the appearance of a toast rack, a feature that garnered both admiration and curiosity.

Architecture critic Nikolaus Pevsner praised it as “a perfect piece of pop architecture,” and it was listed as a Grade II structure in 1998.

The Toast Rack is emblematic of Howitt’s ability to infuse functionality with whimsy. Its striking design reflects both his love for architectural experimentation and his understanding of the building’s purpose.

The adjacent “Poached Egg” building, originally a library and canteen, now serves as a gym. Howitt’s playful approach to the design is not only memorable but continues to serve the community in new ways, long after its original function ceased.

Courts of Justice

Howitt’s vision for Manchester’s public buildings extended to the judicial sphere with the design of the Courts of Justice, completed in 1962. This Modernist structure, clad in Portland stone, replaced the former Manchester Assize Courts, which were also damaged during the war.

The new building housed 17 courtrooms and featured a symmetrical façade adorned with full-height glazing, stone piers, and sculptural details that survived from the original assize courts.

While Howitt’s design received mixed reviews, with Pevsner lamenting it as “a come-down” compared to its predecessor, the Courts of Justice stood as a practical and solemn addition to Manchester’s civic architecture.

To be fair, the old Assize Courts in Manchester were beautiful, and one of the most tragic losses of WW2 bombing.

It symbolised the city’s post-war commitment to rebuilding and progress, a theme that resonates throughout Howitt’s career.

Leonard Howitt’s Vision for Manchester Airport

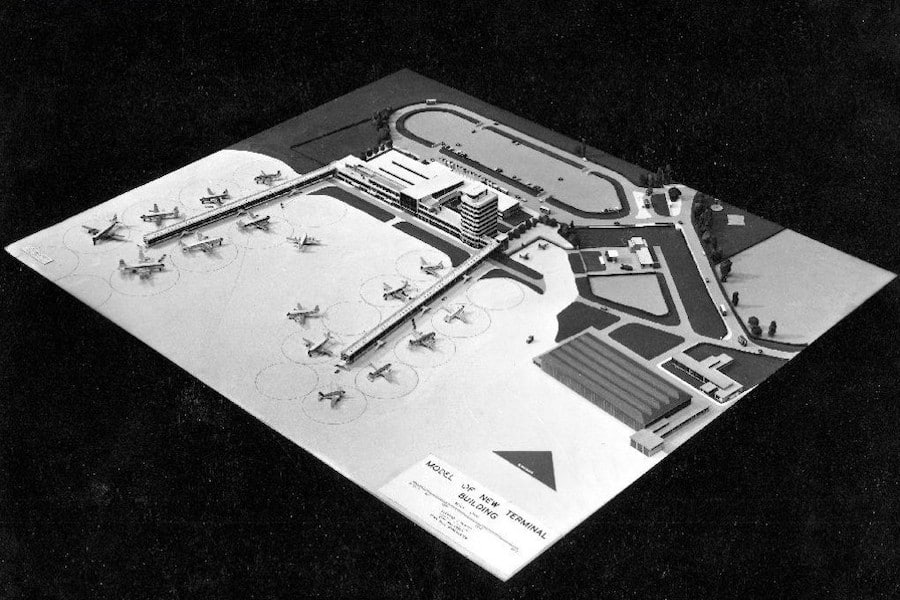

Leonard Cecil Howitt’s work on Manchester Airport, known initially as Ringway Airport, was groundbreaking and forward-thinking. Opening in October 1962, the terminal was designed with modernity, flexibility, and extensibility at its core.

Recognising the need to adapt to future travel demands, Howitt constructed the terminal with a lightweight steel frame and extensively glazed elevations, allowing natural light to flood the building. His design allowed for easy reconfiguration, an essential feature as air travel was set to evolve rapidly in the following decades.

Howitt’s architectural foresight became evident as early as 1955 when he proposed a layout that would efficiently separate passenger and freight traffic. He envisioned a multi-level system where passengers would arrive by car at an elevated entrance, while baggage would be processed at ground level. This structure minimised congestion and was a forerunner to the modern airport experience. Inside, the terminal boasted prefabricated partitions, which allowed quick modifications to accommodate increasing passenger numbers.

Other Notable Works

Howitt’s contributions to Manchester extended beyond these high-profile projects. He was responsible for a variety of utilitarian structures that served the city’s infrastructure and public needs. Among these is the Heaton Park Reservoir Pumping Station, completed in 1955.

This small yet significant structure houses a sandstone relief by Mitzi Cunliffe, celebrating Manchester’s engineering achievement in bringing water from the Lake District. It reflects Howitt’s attention to detail and his willingness to incorporate fine art into public utilities.

Similarly, Howitt designed the Wythenshawe Fire Station in 1957, the Blackley Crematorium in 1959, and various other buildings that, though less iconic, underscore his contribution to Manchester’s urban fabric.

Professional Recognition and Later Life

Throughout his career, Howitt garnered recognition for his contributions to architecture. In 1942, he became a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), and he served on its council for 12 years, even holding the position of vice-president from 1956 to 1958. He was also president of the Manchester Society of Architects from 1955 to 1957, reflecting his standing in the architectural community.

After retiring from Manchester City Council in 1961, Howitt continued to work in private practice with Leonard J. Tucker. He remained active in his field until his death on May 20, 1964, leaving behind a legacy of innovation, public service, and a dedication to Manchester’s architectural heritage.

Leonard Howitt – legacy and influence

Leonard Cecil Howitt’s work captures a unique moment in Manchester’s history—a time of post-war recovery, optimism, and transformation.

His buildings reflect the era’s Modernist ethos, characterised by clean lines, functional forms, and a progressive outlook.

Yet, Howitt’s designs are also distinctly human, incorporating playful elements like the Toast Rack’s whimsical arches or the evocative relief at Heaton Park.

Today, Howitt’s buildings serve as reminders of his contributions to Manchester’s architectural identity.

While some of his works, like the original Manchester Airport terminal, have been modified or obscured over time, others remain cherished landmarks. The Toast Rack, in particular, has achieved iconic status and continues to inspire admiration and debate among architects and residents alike.

In a city constantly evolving, Leonard Cecil Howitt’s legacy endures, both in the bricks and mortar of his creations and in the spirit of innovation he brought to his work.

He remains a key figure in Manchester’s architectural history, a testament to the power of thoughtful design to shape not only a skyline but a community’s sense of place and identity.

You can find out more about Leonard Howitt by clicking here

- This article was last updated 6 months ago.

- It was first published on 11 October 2024 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Head down the rabbit hole for Adventures in Wonderland with Z-arts

Major rail investment set to transform Manchester-Leeds commutes

“His presence will be deeply missed” Children’s hospice bids farewell to their visionary CEO

Has Gordon Ramsay created Manchester’s ultimate bottomless brunch?

The Clink celebrates ten years of empowerment and second chances