The Mancunian boxing champion without a crown – how racism denied Len Johnson his rightful title

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 17 seconds ago

- City of Manchester, Cornerstone, History, People

Len Johnson was a champion in everything but name.

A master of the ring, a fighter of unparalleled skill, and a man who refused to be beaten by opponents or by injustice. He was a warrior who took on some of the best middleweights of his era, defeating men who held the very titles he was denied. Not because he wasn’t good enough. Not because he lacked talent or heart. But because of the colour of his skin.

Born in Clayton, Manchester, in 1902, Johnson should have been a British boxing legend, a household name celebrated alongside the greats. Instead, he was systematically shut out of the sport’s highest honours, locked out by a racist ‘colour bar’ that dictated only white fighters could compete for a British title.

It was an injustice that should have broken him. But Len Johnson wasn’t just a boxer. He was a fighter in every sense of the word. If he couldn’t change boxing, he would change Britain. And that’s exactly what he set out to do.

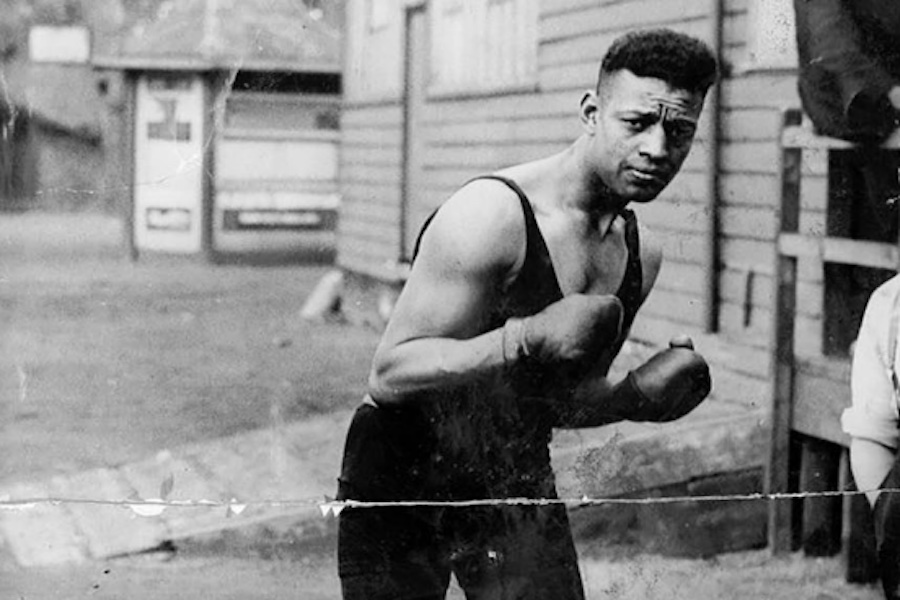

Len Johnson

Leonard Benker Johnson was born into a working-class family. His father, William, was a merchant seaman from Sierra Leone and a former boxer himself, while his mother, Margaret Maher, was of Irish descent.

Growing up in multicultural Manchester, Johnson faced frequent racism, both in everyday life and in his chosen sport. His family experienced hostility, with his mother even suffering a brutal racist attack that left her permanently scarred.

Despite these hardships, Johnson found solace in boxing. His journey into the sport began in the tough environments of boxing booths, where fighters would take on all comers.

These early experiences hardened him, shaping the defensive style that would become his trademark. He turned professional in 1920, quickly establishing himself as a skilled and intelligent fighter with an impressive left-hand jab and an elusive defensive style.

Johnson’s sharp instincts and technical ability helped him navigate the brutality of the ring, allowing him to sustain minimal damage over his lengthy career.

A career overshadowed by racism

Despite his dominance in the ring, Johnson was prevented from fighting for official British titles due to a rule that stipulated contestants had to have ‘two white parents’. This rule, backed by then-Home Secretary Winston Churchill in 1911, remained in place until 1948. This blatant discrimination kept talented Black fighters like Johnson from receiving the recognition they rightfully earned.

One of the biggest injustices of Johnson’s career came in 1925 when he twice defeated Roland Todd, the reigning British middleweight champion, in non-title bouts. Under normal circumstances, these victories should have granted him a title shot, but the British Boxing Board of Control refused to allow him to compete.

His considerable boxing talents saw him go on to record almost 100 victories, some against world champions, but the rule meant he was never given a shot at a championship belt.

British Empire middleweight title

In 1926, Johnson travelled to Australia, where he won the British Empire middleweight title by defeating Harry Collins. However, this title was not recognised in Britain due to the colour bar. On his return home, the British boxing authorities refused to acknowledge his achievements, forcing Johnson to accept that he would never be given the recognition he deserved within the sport.

He continued to rack up victories, defeating world-class opponents like European middleweight champion Leone Jacovacci and light-heavyweight champion Michele Bonaglia. However, these wins did little to change the fact that he was barred from competing for an official championship in his home country. Frustration mounted as Johnson realised that no matter how many opponents he defeated, his biggest fight was against a system that refused to acknowledge his worth.

In an interview with the Daily Dispatch which followed his retirement in 1930, he said he was “fed up with the whole business”.

“I am barred from the Albert Hall, from the National Sporting Club and from all fights where this is big money,” he said.

“The prejudice against colour has prevented me from getting a championship bout, although I consider I am well worthy of one.”

He said if there was a public vote “on the question of whether I should be allowed to take part in a championship bout, there would be an overwhelming majority in my favour”.

“I know in my heart that I shall never achieve those ambitions, so I am getting out of the game,” he added.

Life after boxing and political activism

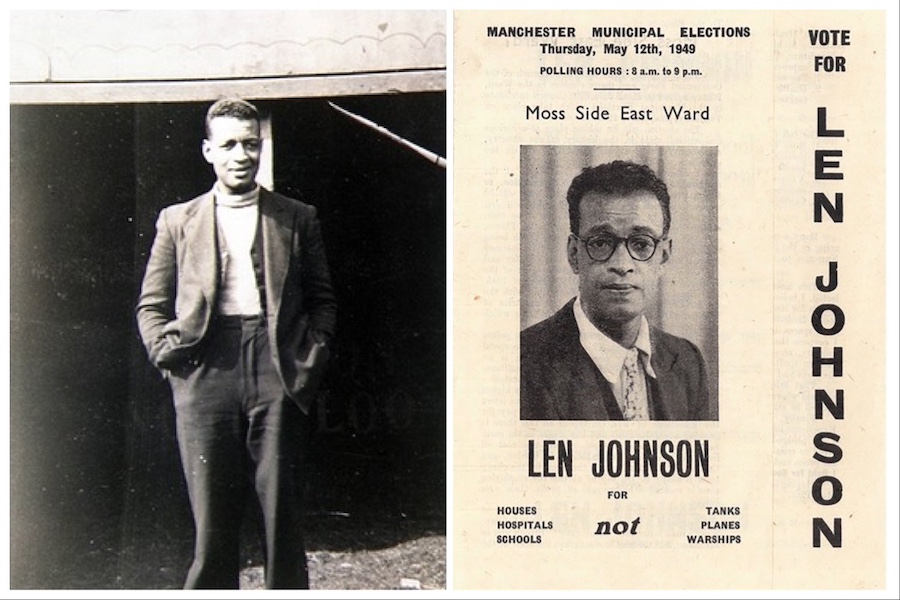

By 1933, Johnson had grown weary of the injustice in boxing and retired from the sport. However, his determination to fight injustice did not wane. Instead of fighting in the ring, he took his battles to the streets, becoming an outspoken advocate for racial equality, workers’ rights, and social justice.

He joined the Communist Party and became a key figure in Manchester’s labour movement. Johnson was instrumental in founding the New International Club in Manchester, a centre that provided support and organisation for Black communities facing discrimination.

The club became a hub for discussions on race, workers’ rights, and anti-colonial struggles. He was also involved in organising events, including a rally featuring Paul Robeson, the African American singer and activist, in support of the Trenton Six—African American men falsely accused of murder in the United States. His ability to bring together diverse voices in the fight for equality cemented his reputation as a leader beyond the boxing world.

His activism extended beyond Manchester. Johnson played a role in the Pan-African Congress, which was held in the city in 1945. This event was a key moment in the decolonisation movement, bringing together figures such as Kwame Nkrumah, who would later become the first Prime Minister of an independent Ghana. Johnson’s efforts helped draw international attention to issues of racial discrimination, colonial oppression, and the struggle for civil rights.

Beyond politics, Johnson remained deeply connected to his local community. He ran for Manchester City Council six times, though he was never elected. Despite this, he remained a respected figure in Moss Side, known for standing up against racial discrimination and economic inequalities. He frequently intervened in cases where Black Mancunians faced discrimination in housing, employment, and policing, ensuring that they had support and representation.

The push for recognition

Although Johnson’s contributions to boxing and activism were groundbreaking, he remains a relatively unsung hero in Manchester’s history. His great-granddaughter, Darianne Brown, has joined a campaign to erect a statue in his honour, highlighting the lack of Black historical figures commemorated in the city.

Actor Lamin Touray, who is also involved in the campaign, has spoken about the importance of Johnson’s story, drawing comparisons to boxing legends such as Muhammad Ali. Touray has argued that Johnson was Manchester’s own version of Ali, a fighter both in and out of the ring, whose struggles against racial discrimination should never be forgotten. Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham has publicly supported the campaign, stating that Johnson’s story “absolutely needs to be told and celebrated.”

Manchester City Council has acknowledged the need for a statue, though a location has yet to be agreed upon. The campaign continues, driven by those who believe that Johnson’s legacy deserves proper recognition in the city he fought so hard for.

You can check out the statue campaign by clicking here

Robbed of a title

Johnson’s influence extended well beyond his own lifetime. Though he never got the opportunity to compete for a British title, his relentless campaigning contributed to the eventual abolition of the colour bar in 1948, paving the way for future Black British boxers to compete on equal terms. Fighters like Randolph Turpin, who became Britain’s first Black boxing champion in 1948, owed a great deal to Johnson’s perseverance in challenging the injustices of the sport.

His work in Manchester’s communities made a lasting impact. He was a relentless advocate for racial equality and working-class solidarity. He may not have held a championship belt, but his efforts changed the social landscape of the city, ensuring that future generations would not have to endure the same barriers he faced.

Johnson passed away in 1974, but his legacy lives on. Today, a campaign is underway to honour him with a statue in Manchester, recognising not only his achievements in boxing but also his contributions to civil rights. The campaigners, including his great-granddaughter Darianne Brown, argue that Manchester lacks statues of Black historical figures, and Johnson’s story deserves to be told and remembered.

Why Len Johnson’s story matters today

Len Johnson’s story is one of perseverance and resistance against injustice. He was denied the opportunities he deserved, but he refused to accept defeat, dedicating his life to the fight for equality. His name may not be as widely known as some of the boxers he fought alongside, but his impact was far greater than any championship belt.

As Manchester continues to celebrate its diverse history, Johnson’s story remains as relevant as ever. He was more than a fighter; he was a champion of justice, and his legacy should be remembered as such.

His life is a showcase of the power of resilience, proving that the greatest victories are not always won in the ring, but in the fight for fairness and equality.

- This article was last updated 17 seconds ago.

- It was first published on 24 March 2025 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

How LOWRY’s writing challenge is encouraging kids to explore their imagination

Manchester music legend steps in to help young bands against unfair merch fees

Manchester’s tallest tower to host Hollywood A-lister backed hotel and restaurant

Ukrainian artist studying in Manchester shares inspiring message about living life to the full