“We still sell more records than all of the other ‘Manchester bands’ put together” Noel Gallagher interview

- Written by Louise Rhind-Tutt

- Last updated 4 years ago

- Books, Music

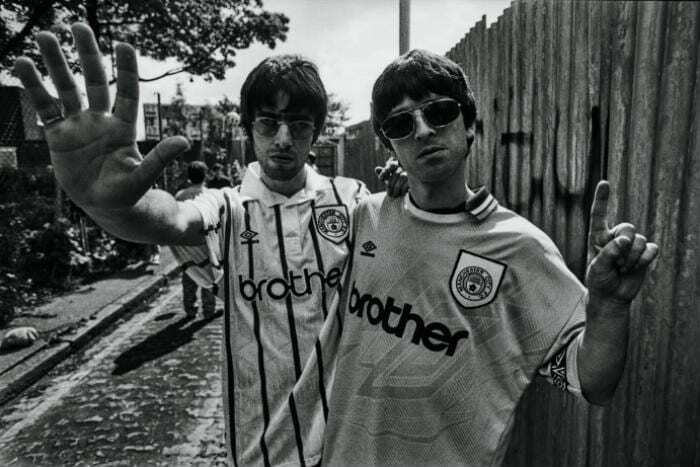

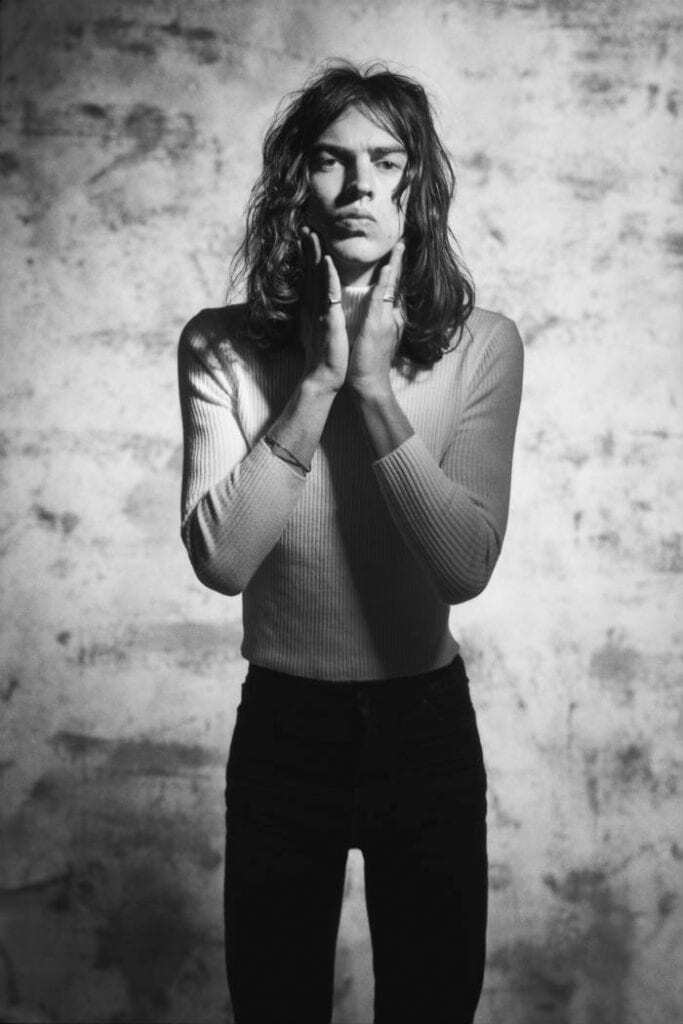

Photographer Kevin Cummins documented the rise and fall of Cool Britannia – now his new book discusses its legacy with key players.

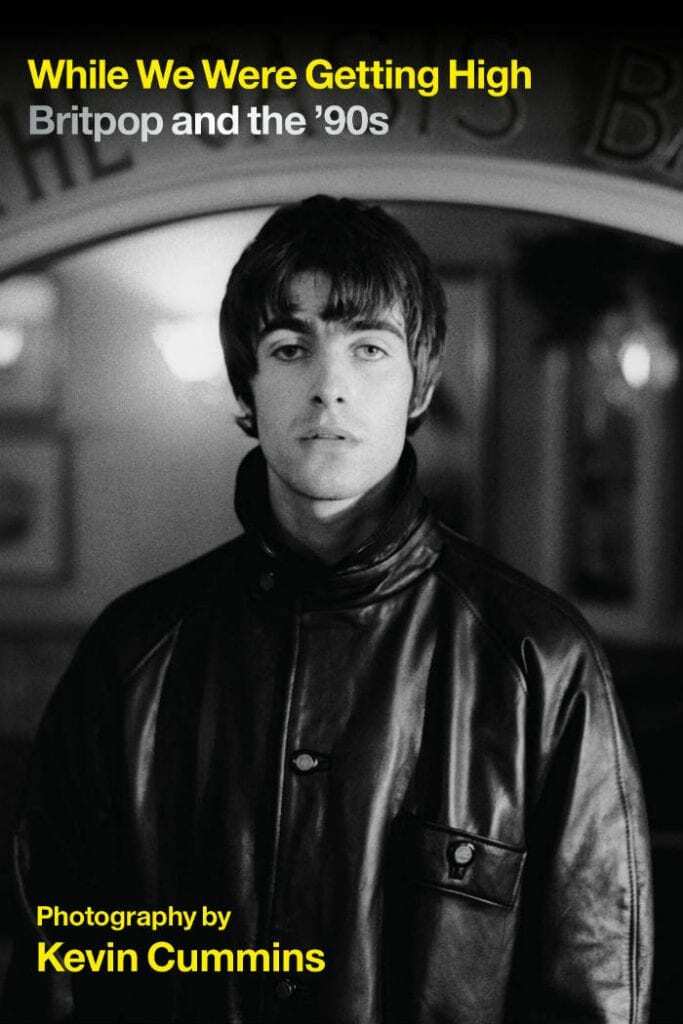

Kevin spent the 90s as chief photographer at NME, and his new book While We Were Getting High is a nostalgic look back at the Britpop era through hundreds of striking photos – many never seen before.

A must for any 90s indie kid, the book includes portraits of Oasis, Blur, Suede, Pulp, Elastica, Supergrass, Gene, Sleeper, Kula Shaker, Echobelly, Menswear, The Bluetones and more.

Greater Manchester bands and artists play a large part, of course – from The Verve and Wigan’s Richard Ashcroft to The Charlatans, whose singer Tim Burgess was born in Salford.

“I usually define my job as 10 per cent photography and 90 per cent hanging around hotel lobbies waiting for the band to turn up,” writes Kevin in the introduction.

“It’s kind of ironic that the photo of Liam was taken while I was sitting in a hotel lobby in Newport, Gwent, and when he eventually turned up he was perfectly framed by the door with “The Oasis Bar” sign above his head”.

The photo in question was the front page of the NME in June 1994, and is also the front cover of the book.

“I’ve always thought it was a good cover…” said Liam Gallagher in a 2012 interview with NME.

“I remember buzzing off it and showing it to me mates and that. That’s where I’m meant to be – on front covers.”

The book also discusses the legacy of the Britpop era with key players, from Noel Gallagher to Brett Anderson.

In the below extract from the book, Noel discusses the impact of Britpop, 25 years on.

Noel Gallagher on Britpop

It’s 25 years since Britpop – how do you look back at that time? Has it aged well?

“Looking back on it now, I think Charles Dickens might well have summed it up best in 1859 when he wrote: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. Has it aged well? Yes and no. The attitude of the main players was correct and even some of the music still stands up, but sadly the cartoonish element of it has been allowed to survive.”

Did it feel like you were all part of a scene?

“Oasis wasn’t part of any scene, not even in Manchester. The “scene” had already taken root a few years before. Blur and Suede had their foot in the door long before what came to be known as Britpop was even a thing.”

Did you feel any kinship with other indie artists of the time?

“Absolutely not. In fact, it wasn’t until Pulp entered the room that we found anyone remotely like us.”

What did you think was the catalyst for the crossover from indie to mainstream?

“Oasis. Pure and simple. Blur and Suede were having hits and were quite successful, but we literally smashed it wide open. The NME had to invent a collective so that every other fucker could ride on our coat-tails.”

Do you feel that lumping bands together under the Britpop label was enhancing or demeaning for you and for the other bands?

“I thought it was a bit demeaning for us but, as I said, the NME had to lump everyone together or we would have put everyone out of business. I couldn’t give a fuck about the rest of the bands. Well, I certainly didn’t then anyway.”

Oasis was the last great rock ’n’ roll band of the analogue era. Do you feel that if you got back together, even for one show, that you could ever capture that magic again?

“Musically, yes absolutely. The music still stands up so how could we not? The audience thought would be vastly different. Camera phones, people filming it, snowflakes, all the woke people at the back tut-tutting, the tourists. It’s best left in the past where it belongs.”

Did you feel you were flying the flag for Britain and British music?

“Erm…no.”

Do you see yourself as a Manchester band, part of the fabric of the city?

“Now that is a tricky one. You see the likes of Paul Morley and the old Russell Club arty types would almost certainly say no. People like them are not people like us, but fortunately, they don’t own that town. The people do, and whether they or you like it or not we are a part of its musical furniture. And we sold more records than all of the other “Manchester bands” put together. Still do. Always will. So…fuck ’em all is what I say.”

Do you think that being associated with Manchester is restrictive?

“Very early on, most likely before anyone had actually heard “Supersonic”, when it was asked “Where are they from?” and our people would say Manchester, there would be a rolling of the eyes as Manchester bands at that time tended to have a certain sound. But, on the whole, no, not at all. Why would it?”

Extracted from While We Were Getting High: Britpop and the ’90s by Kevin Cummins, published by Cassell Illustrated, £30, octopusbooks.co.uk

- This article was last updated 4 years ago.

- It was first published on 30 October 2020 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Head down the rabbit hole for Adventures in Wonderland with Z-arts

Major rail investment set to transform Manchester-Leeds commutes

“His presence will be deeply missed” Children’s hospice bids farewell to their visionary CEO

Has Gordon Ramsay created Manchester’s ultimate bottomless brunch?

The Clink celebrates ten years of empowerment and second chances