The forgotten dream of Manchester’s underground network

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 1 year ago

- Cornerstone, Featured, History

Beneath the bustling streets of Manchester lies a forgotten dream – the Picc-Vic Tunnel, an audacious project conceived in the early 1970s to seamlessly link the city’s heartbeat, Piccadilly and Victoria stations.

Picture a web of underground tracks weaving through Manchester’s urban core, promising a transit revolution that never saw the light of day.

Back in the day, Manchester found itself at a crossroads.

Unlike London, where the Underground united stations seamlessly, Manchester’s central business district lacked the rail accessibility it deserved.

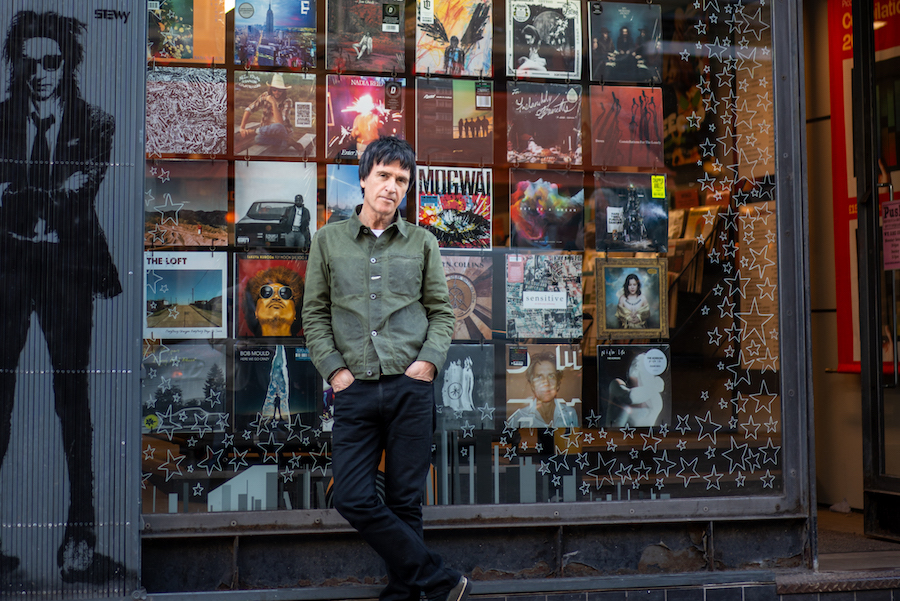

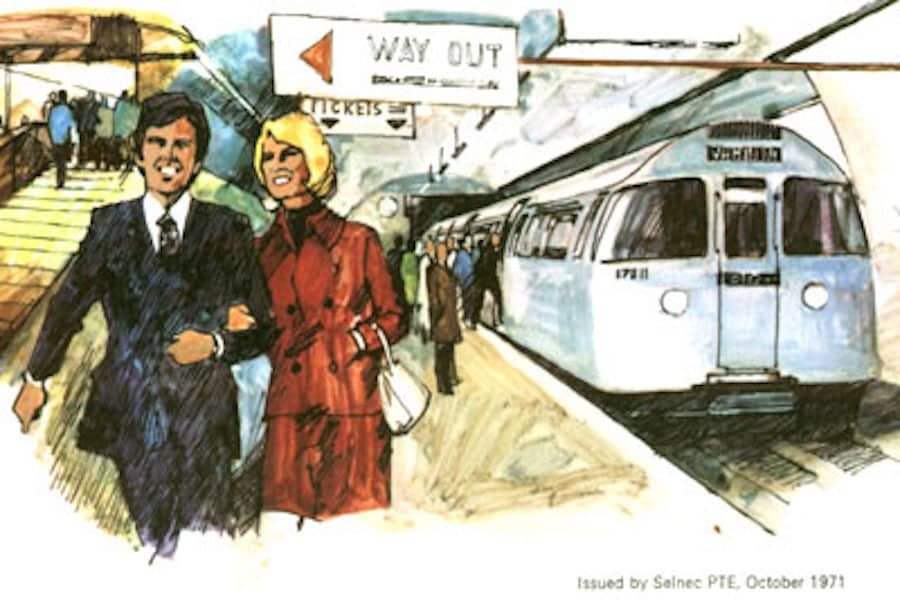

Enter the South-East Lancashire and North-East Cheshire Passenger Transport Executive (SELNEC PTE), later rebranded as the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (GMPTE), armed with a vision: the Picc-Vic proposal.

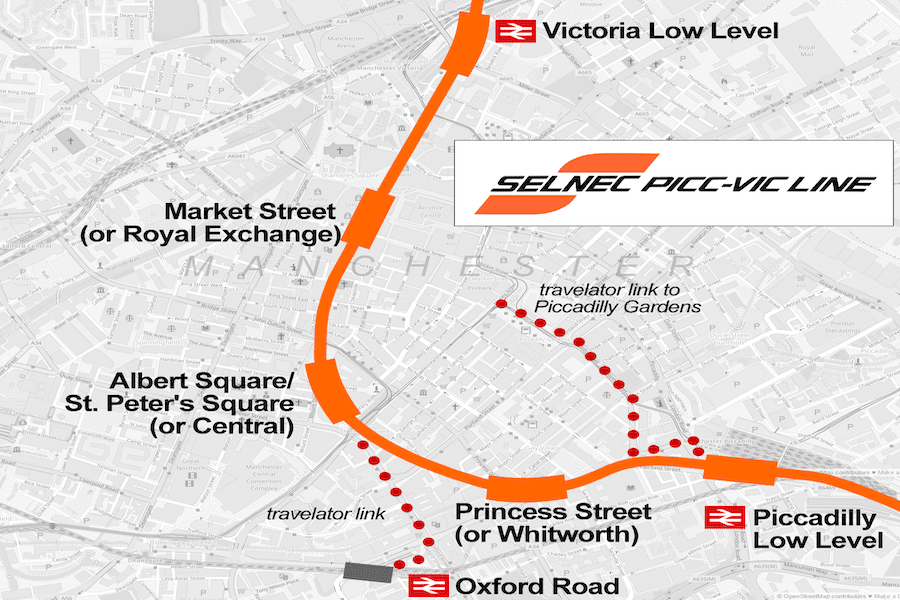

Imagine new tunnels snaking beneath the city, connecting Piccadilly and Victoria with a rapid transit system tailored for Manchester.

The grand plan included five stations, two low-level platforms, and an underground network accommodating up to eight-car trains.

But this visionary venture met an untimely demise in 1977, succumbing to financial hurdles and the challenge of maintaining two colossal terminal stations.

So would it have been a game changer or a dud? Here are the facts about what could have been..

What was the Picc-Vic Tunnel?

Picc-Vic, an ambitious underground railway project conceived in the early 1970s, aimed to seamlessly connect Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria

The vision behind Picc-Vic involved the creation of an underground rail tunnel spanning across Manchester’s urban core.

The Proposal

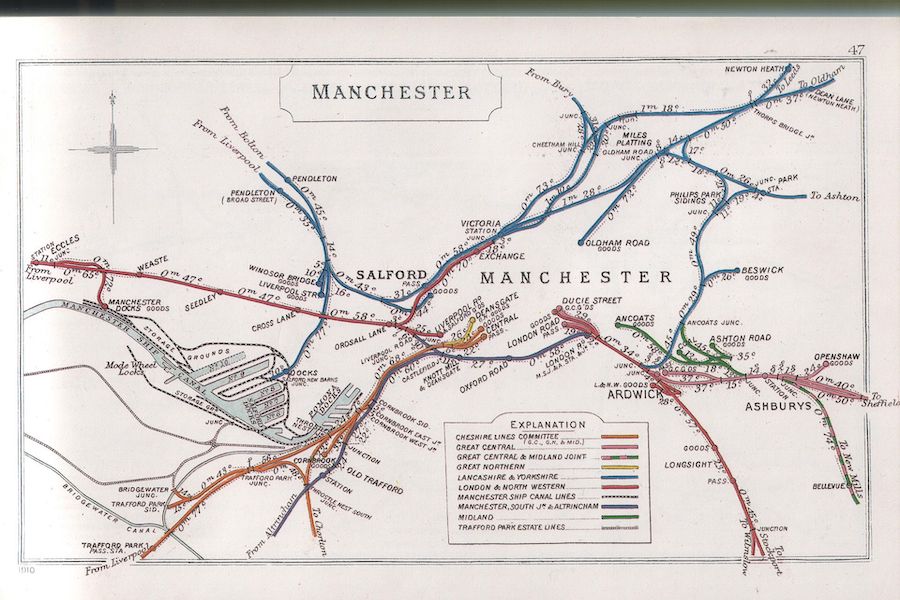

The railway infrastructure established during the 19th and 20th centuries by multiple railway entities led to the development of disparate railway termini on the outskirts of Manchester’s city centre.

In contrast to the centralised approach adopted by London, where the London Underground connected its stations, Manchester faced a situation where a considerable portion of its central business district lacked accessibility through rail transport.

Why did the Picc-Vic Tunnel Fail?

This innovative proposal, however, met its demise in 1977 during the early stages of development, primarily due to soaring costs.

The persistent presence of two large and economically burdensome terminal stations in Manchester further fueled the decision to abandon the scheme.

Interestingly, similar-sized cities had opted for a single terminal, making the Picc-Vic project appear financially untenable.

SELNEC sought financial support from the central government to fund the construction of the Picc-Vic line.

This initiative occurred during the early 1970s when the United Kingdom faced economic challenges.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Anthony Barber, in response to economic difficulties, announced a substantial £500 million reduction in public expenditure.

In August 1973, the Minister for Transport Industries, John Peyton, rejected SELNEC’s grant application, citing the prevailing economic constraints.

Peyton stated that “there is no room for a project as costly as Picc-Vic before 1975 at the earliest.”

The nature of an underground excavation and construction project demanded a significant upfront investment from public funds.

When the Greater Manchester County Council took charge of the project, it encountered difficulty in securing the necessary financial support from the central government.

As a result, the Picc-Vic scheme faced abandonment in 1977 due to the overwhelming cost associated with its implementation.

The Death of the Picc-Vicc Underground Tunnel

Fast forward to 1992, and the unveiling of the Metrolink system transformed the transportation landscape in Manchester.

The tram system intelligently connected both Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria, alleviating the need for a direct rail connection to some extent.

This development marked a practical alternative to the grand underground scheme envisioned in the Picc-Vic proposal.

The Ordsall Cord

The year 2017 witnessed the operational debut of the Ordsall Chord, a significant overground railway initiative.

It was this, or the Picc-Vic concept, according to reports, with the Ordsall Chord winning in the end.

This scheme, akin to the initial Picc-Vic concept, established a direct link between Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria.

The Ordsall Chord’s implementation offered a contemporary solution to the connectivity challenge, bringing to fruition a vision that had eluded realisation decades earlier.

The Legacy of the Vicc-Picc Tunnel

In 2008, a resurgence of interest in an underground rail link beneath Manchester emerged, more than 30 years after the original project was abandoned.

Ruth Kelly, the Transport Secretary and MP for Bolton West, announced a Department for Transport study to reassess rail provision in the area.

However, by the 2011 United Kingdom budget, a new plan took shape under the guise of the Ordsall Chord.

In 2012, researchers from the Manchester School of Architecture at the University of Manchester conducted an investigation beneath the Arndale Centre in the city centre.

Their discovery unveiled a long-forgotten subterranean void approximately 30 feet (9.1 m) below the surface.

This void had seemingly been incorporated into the shopping centre’s construction in the 1970s, to facilitate a link to a new Royal Exchange underground railway station when the originally planned Picc-Vic tunnel was set to become operational.

So what do you think? Would this have been good? Or a huge waste of money. Fancy Manchester with an underground…

Let us know! thom@ilovemanchester.com

- This article was last updated 1 year ago.

- It was first published on 19 December 2023 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

The Manc aerobics queen who trained the Corrie cast is helping raise charity cash

Ancoats to get even cooler as independent market set for MOT garage site

“Manchester is not Britain’s second city, it’s the first” – Jeremy Clarkson