We all have a personal map of Manchester in our memories

- Written by Dave Haslam

- Last updated 2 months ago

- City of Manchester, Cornerstone, Culture, Featured, History, People

I remember when it was rare to see tourists in Manchester. You’d have people coming here to shop, watch football, or drink or dance, but you were unlikely to meet anyone from abroad, a genuine tourist wanting to look around the city.

The first tourists I met were from Holland, two lads standing around in HMV on Market Street. They’d come to be near the Fall, they worshipped Mark E Smith. I sent them to Prestwich, suggested they pop into the Foresters, or, failing that, the Woodthorpe; sooner or later (probably sooner) Mark would be in one or either.

Our personal maps of Manchester

Now we have tour guides, and a roll call of tourist sites, including the John Rylands Library, MOSI, the Art Gallery, and recent additions reflecting the city’s radical history; the Pankhurst statue and the Peterloo memorial.

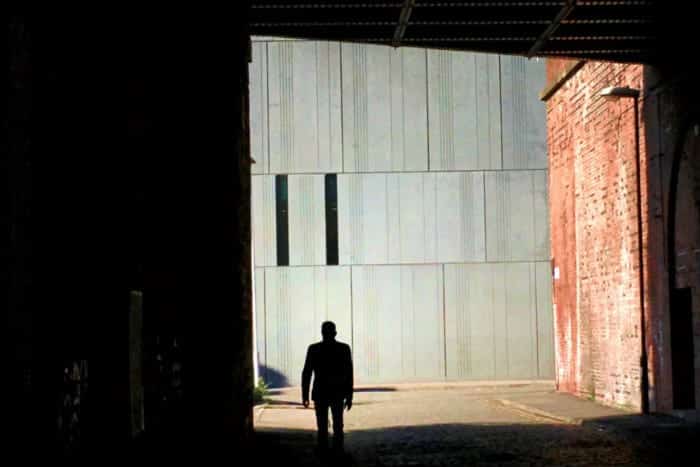

I’ve been thinking, though, of how everyone has a personal map of the city they live in; places with an important, but private significance.

In the story of our lives these places that mean everything to us aren’t necessarily on the tourist trail or featured in city guides. A bus stop where you’d anxiously wait for the nightbus, a café you idled away hours in, a shop you’d visit because you had a crush on one of the assistants…

These are places that create our personal histories, sites with an emotional meaning that connect us to the people we once were, and connect us to communities and the people we have lived among.

Of course some places might remind us of negative experiences; the pub you were in when you received bad news, an office you wished you’d never taken a job in.

Good times, bad times

There are several sites I can’t walk past without being reminded of my happy life in music, including an MMU building on Cavendish Street that used to be student union premises, where I saw bands including the Dead Kennedys, the Gang of Four, U2, and the Fall.

My personal map of places with an emotional charge includes Marie Louise Gardens, off Palatine Rd on the edge of Didsbury. I’d take my children there when they were little, have a walk, see the squirrels, run through the leaves, witness the seasons changing.

I have studied inside Central Library for hours, but the steps into the building still remind me most of waiting for friends, in an era before mobiles; when you and your friends would have your favourite spots to arrange to meet up.

I can’t walk near one corner of Afflecks Palace without remembering my part-time job there, at Identity, in 1985; and the people I met through that job.

There’s a particular block on Newton Street, an old warehouse at the Piccadilly end of the street. There’s a martial arts centre on the first floor – just as there was when I first started going into the building, in 1987, to get my haircut by a barber with a shop on the ground floor. Starstyles, it was called. And it was presided over by Lew Starr.

The music venue, Jimmy’s, has just moved from the building after being served an eviction notice; apparently the old warehouse is set to be redeveloped into offices.

Lew was probably in his late 60s when I met him, but he had decided never to retire from his barbershop. “This is where my friends are,” he’d say.

Lew would ask me to make him a cup of tea. He’d introduce me to the other customers, many of them regulars since the 1950s. One day there I met a man who’d fought in the Spanish Civil War. My claim to fame was inadequate in comparison; Lew would tell the other customers “Dave works at Tony Wilson’s club”.

It was his third shop in town. In the late 1950s, Lew was on Charles Street, providing everything from a short back and sides to the latest teddy boys looks. By the mid-1960s, the scowling teddy boys were replaced by mods who’d park their scooters outside the shop on a Saturday morning.

Charles Street

His sons Ian and Martin worked alongside him in Charles Street. Ian was there more-or-less ten years, at the same time holding down jobs playing drums in various Manchester bands, including the Richard Kent Style.

The Charles Street barbershop was subject to a compulsory purchase order when the BBC building was planned, so Lew moved to Whitworth Street, then Newton Street.

I didn’t know any of this when I first walked through the door, this was just a little of what we talked about in the ten years or so when I was a very regular visitor to Lew’s barbershop.

I also met Ian. Then one evening when I was DJing at the Boardwalk, a young guy introduced himself to me as one of his grandsons. And then, a few years later, out and about, I met Lew’s granddaughters.

I never met Lew’s other son, Martin; tragically, he died in the very early 1970s in a road accident.

I met Lew’s wife a few times, though, when our paths crossed in the shop. At Lew’s funeral she introduced me to their friends. “This is Dave, he used to work in Tony Wilson’s club”.

Next door to Lew’s barbershop was a basement nightclub called Papa’s (it later became the Roadhouse). On the groundfloor was the Alasia snack bar, a decent meeting place, with cheap tea and toast. A band called Laugh name-checked the snack bar in a song called Take Your Time, Yeah!

Once we’ve formed an attachment to these special places they join all the other sites that jog our memories, give us our sense of belonging, and connect us to people and absent friends.

As, inevitably, inexorably, the city’s landscape changes, it gets harder to hold on to these connections. And when these memory-wrenching places are demolished, a little part of us disappears too.

- This article was last updated 2 months ago.

- It was first published on 6 January 2020 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Chorlton Library gets a stunning renovation unveiling hidden treasures

How one selfless act sparked a career dedicated to saving lives

Former sheltered housing transformed into safe haven for vulnerable youth

Manchester and Los Angeles prove that opposites really do attract