God bless Tony Wilson – how Mr Manchester helped us all to love our city

- Written by I Love MCR

- Last updated 2 months ago

- Cornerstone, Culture, Featured, People

It’s a dirty dozen years since Tony Wilson died. There’s still a Wilson-sized hole in Manchester – and it’s hard to imagine when there will be a time when there isn’t.

Everything we have now seems to have been inadvertently inspired by Tony and the group of people he worked with – Rob Gretton, Alan Erasmus and Martin Hannett.

How he helped us all to love our city

Words by Terry Christian

So here’s the Tony Wilson I knew.

As a youngster, I grew up in a Manchester cut off from aspiration and inspiration, our lives and expectations as narrow as the streets we lived in.

Suddenly there’s this madly enthusiastic bloke on the telly showcasing The Buzzcocks, Sex Pistols and Joy Division, telling us that where we lived was beyond mere cool. So we’d go to all the punk gigs, and Tony would be there, sticking out like a sore thumb in his suit, being universally slandered, yet he opened a window on a different world for us.

He was our man off the telly demystifying that elusive world of possibilities that beckoned.

A volcano full of constantly erupting ideas; an intimidating amount of confidence; a sort of fearlessness; never on time; never stuck around for more than thirty minutes unless on home territory; always had time albeit transient; always engaged with people on a one to one basis; always positive, even about ridiculous ideas at times; always encouraging – even about other people’s ridiculous ideas; always loved an argument; rarely bore grudges; and a hide like a rhino.

He was to all intents and purposes exactly what we needed in Manchester and need now more than ever. He was a figurehead – and a walking coconut shy at the same time.

Everyone had an opinion about Tony. He was hated, adored yet never ignored – just like his beloved Manchester United. He was sometimes wrong and would admit it – eventually – but he always had an opinion. That in itself was exciting and different – a charismatic arrogance that was so un-serf like that it was hypnotising to us working class Manchester kids – and very attractive. There’s nothing as life sapping as someone without an opinion.

It’s a form of laziness, like they can’t be bothered engaging with life. That was never the case with Tony. So after all this waffling, what exactly did Tony do that made him so special?

Here we go.

Mr Manchester

Tony Wilson aka Mr Manchester once said: “Most of all, I love Manchester. The crumbling warehouses, the railway arches, the cheap abundant drugs. That’s what did it in the end. Not the money, not the music, not even the guns. That is my heroic flaw: my excess of civic pride.”

I first met Tony Wilson back in 1978. A gobby inner-city teenager haranguing a TV presenter to put more reggae on his So It Goes TV show. The mere fact he engaged with me for five minutes gave me a thrill.

He didn’t try to be all Manchester council estate; he remained the arty Cambridge graduate and didn’t pull any punches. I thought he was a bit ‘poncy’, especially as he called me ‘darling’, but I was fascinated by his passion for our city, a fascination that never diminished in almost thirty years.

The abuse Tony would get meant he was like a walking coconut shy, opinions bulldozing through sensibilities. Nevertheless, he pushed for it all at nightclubs, bars, city centre apartments, and redevelopment; he made Manchester attractive to the creative industries and the young talent who would work in them.

It was beyond cool. It was saying here’s a city that doesn’t care about where you’re from, show us what you can do, and we’ll respect you because here we’re not about making mere money; we want to make history.

Back in 1982, I got my first presenting job and a nightly music magazine show called Barbed Wireless on BBC Radio Derby. I wanted it to be opinionated, accessible and use to boost the local music scene.

When I got a tape off a good band, I’d naively ring Tony up at Granada. He hardly knew me, but he’d always pick up the phone and chat, telling me stories and giving advice. That radio show won two consecutive Sony awards for the best specialist music show, and I did get the locals focusing on creating their own scene. But it was just me aping Tony and trying to recreate a mini-Manchester in Derby.

In 1986, he suggested to the Manchester Evening News editor that he should do a page covering the Manchester music scene. It was Tony’s Machiavellian way of getting more exposure for the bands on his Factory label, but it worked out for everyone on the local music scene.

A music page in the Evening News, in turn, created a demand for dedicated shows on local radio covering Manchester music. That page was known as The Word, and I took it over in 1989. It would ultimately be where bands like The Stone Roses, The Charlatans, Oasis, Doves, even Take That would get their first press.

The name The Word would be suggested by me in turn to Channel 4 for a new youth programme they’d employed me to present. The Word, in turn, gave the first TV appearances to Oasis and Nirvana and is still talked about now 25 years after it finished.

When I needed advice about TV, there was only one person I’d ring. The advice was: “do it your way and make sure you put something back.”

So from that tiny punk scene in 1976 in Manchester, we’ve produced influential music like Joy Division, New Order, The Smiths, James, The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, Doves Oasis, The Courteeners, Blossoms, Children Of Zeus, Aitch, IAMDDB and Bugzy Malone. The charts have been littered for the past 30 years with Manchester originated pop and dance tunes, the radio stations play stuff by Manchester bands, and the city has become a Mecca for music worldwide.

Tony’s advice still resonates, put something back, and more will grow.

I’d often bump into Tony and his son Oliver at United matches, where we shared a passion for the reds. Tony was my half time comfort blanket when United was struggling in tricky European ties – “we’ll win this one, Terry, there’s no doubt” – and he was almost always right.

I was lucky enough to work with him on TV and radio. I recall Tony saying that it was the job of Mancunians to annoy everyone else, exoneration and benediction for me. So don’t be ignored, don’t be overlooked.

Despite international cult status, Tony was our triumphantly private touchstone and far from perfect. But then, we’re all loved for our imperfections. So the fact he’s no longer there to share his thoughts is a supreme irritant.

What was Tony Wilson really like?

Tony’s door was always open. He’d always engage, take a phone call and give a helping hand – or even some unhelpful advice.

When I was first presenting The Word on Channel 4, I was feeling frustrated about the number of arguments I was having to get certain bands and guests I wanted on the show. Everything, it seemed to me, had to go through the Home Counties posh kid media prophylactic. And if what they put on was shit, I felt that was damaging my ‘brand’ as they’d call it now.

I rang Tony and asked him, ‘Tony, when you’re the presenter of a TV show, how much say should you have in the programme content?’ He paused for a minute then said quite solemnly ‘Hmm 11.5%. That’s exactly it. 11.5% I’d say’.

I found myself mesmerised and dumbfounded and said ‘Thanks Tony’ and hung up – and then thought ‘What the fuck does that mean?’ Oh yes, he could do that, a sort of Jedi mind trick that had New Order pouring all their money into the Hacienda for 15 years.

Tony could do anything – and excel at it. He was a brilliant TV presenter. As a teenager, I used to sort of hate him when he did So It Goes and Granada Reports but I was fascinated by him.

He saw where I lived but through double rose tinted spectacles. He’d bring bands on that were different and introduced me to The Sex Pistols, Ian Dury, Iggy Pop, Elvis Costello, The Clash, and – more importantly for us Mancunians – a band we already knew about – Buzzcocks.

He made where we lived seem exciting. He’d interview people like Anthony Burgess and intellectualise about the nature of Mancunians and working class people and our place in the world and the worthwhile contributions we could make.

He wasn’t telling me what to think, but almost challenging me and others about how I thought and actually making it cool to know stuff and to read books.

I’d watch and think ‘posh twat’ then carry on watching and tune in next time, fascinated and determined to expand my reading at least.

[Go on Terry, tell us how you really feel]

Manchester has just had its latest international arts festival. No way would that have happened without Tony Wilson, nor would the Commonwealth Games.

So City fans enjoying the stylish comfort of the Etihad have to thank a United fan for that, although we should also never forget the contribution of Tony’s partner in crime at Factory Records and devil on Tony’s shoulder, the late Rob Gretton – as true a blue as ever existed and still sorely missed and totally under-appreciated in Manchester.

The Commonwealth Games came from Manchester’s cheeky failed bid for the Olympics, an idea that came from Tony. He basically told the council, ‘you’re in charge of a big city, start acting like it’.

Tony Wilsons’s In The City international music seminar in Manchester taught the council that these events brought money into the city and they were very quick learners. Now we have numerous arts, literature and music festivals in Manchester throughout the year.

Tony Wilson’s vision

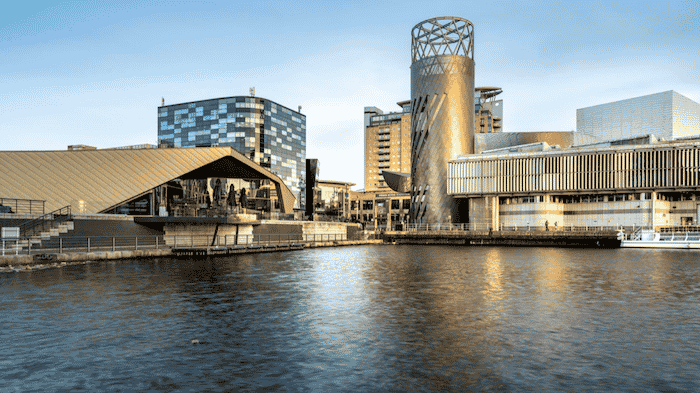

You talk about city centre living and how it can feed the culture of a city. It was Tony’s vision after visiting New York and seeing loft apartments in old warehouses and mills. But would it work in Manchester and elsewhere? Just ask Tom Bloxham of Urban Splash.

Walk through most city centres or trendy areas nowadays and look at the names of the bars. All one word names. The first place to do that in Manchester was Dry. It was originally going to be called Dry and Hungry – a bar on the ground floor to get a drink when you’re ‘dry’ and a restaurant on the second floor for when you’re ‘hungry’.

Factory ran out of money and decided they couldn’t afford the restaurant so just used half the name. After that, every bar in the Northern Quarter had a one word name – Blu, Common, Cord, Trof – and it went the same way outside Manchester. Genius branding cooked up from the mind of a true genius.

As for Tony’s own ambitions, yes he wanted and deserved recognition. He should have had his own arts show on Channel 4 or BBC 2.

I groan inwardly every time I see Yentob and his ilk, sons of privilege trying to communicate the world of ideas to an audience that they have never moved amongst. As the old Irish saying goes, ‘Those in power write the history, those who do the suffering write the songs’.

Thanks to Tony, four big films have been made set against a backdrop of the Manchester music scene between 1978-1990 – 24 Hour Party People, Control, Spike Island, and Made Of Stone – and numerous books about Manchester bands.

Is there a kid in the country nowadays who picks up a guitar and doesn’t start off by learning how to play Wonderwall? Culturally and historically, that sort of stuff is like an atom bomb. Manchester has a history and generations will absorb and remember and add to it.

That was Tony’s vision and it’s mission accomplished. God bless you, Tony, wherever you are. You helped us all to love our city.

God bless Tony, from all of us who’ll never forget.

His excess of civic pride

Words by Ray King

The last time I met Tony Wilson, who died on Thursday 10th August 2007, he had just resigned his job as presenter of Granada Reports – the show that made him a household name – to campaign for an elected regional government in the north west.

It was an initiative floated by Tony Blair’s Labour government in the summer of 2003 and spearheaded, if that’s an appropriate term in the circumstances, by the pugilistic and ebullient John Prescott. The deputy Prime Minister’s ambition split the nation – but not, as he intended, into self-governing regions. Rather, it divided opinions.

In the north west, a coterie of local personalities including Wilson, comedian Steve Coogan who, ironically, played him in the movie 24 Hour Party People, Sir Alex Ferguson, then manager of Manchester United and Happy Mondays’ frontman Shaun Ryder, enthusiastically backed the plan and formed The Necessary Group to take the campaign forward.

Manchester’s leading politicians however, were dead against – so much so that MP and former Manchester city council leader Graham Stringer almost came to blows with Prescott on stage during a public debate. Manchester’s preferred option was for a city region – along the lines of the former Greater Manchester area – which came to pass early in 2017 with the election of executive mayor Andy Burnham who had an eventful first 100 days to say the least.

Tony Wilson’s place

Though Tony Wilson has been dubbed “Mr Manchester” for his legendary status in the city’s Madchester music scene, having launched Factory Records and the Hacienda night club, his horizons spread further, imagining a mythical territory of “Granadaland” – a term now all but airbrushed from history by ITV – as a self governing entity.

In the early weeks of 2004, when I was a columnist with the Manchester Evening News with a broadly sceptical view of Prescott’s plans, he rang me about a brilliant idea he’d had and suggesting I take him out for lunch over which he’d reveal all.

We went for a thali at Shimla Pinks, an Indian restaurant opposite the Crown Court in the pre-Spinningfields era. He pulled from his pocket a piece of paper on which was drawn the top left hand quarter of the English flag, the Cross of St George.

“It’s the north west’s own flag,” he exclaimed triumphantly, revealing that the proposed design was created specially by Peter Saville.

“The design is brilliant and searingly obvious,” said Tony. That much I got. What I didn’t get was his claim that the design recalled the Peterloo Massacre when the cavalry charged a large political gathering and seized its flags.

As things turned out the only time the flag made it up a flagpole was when it was photographed by photo-journalist Aidan O’Rourke.

For when the first referendum was staged in the north east of England – considered by Prescott to be the most likely region to support his version of devolution – voters rejected it by 700,000 to 200,000. The defeat was so crushing that Prescott abandoned plans for votes in the north west and elsewhere.

Tony’s complete misreading of the political mood revealed a rather endearing naivety that contrasted with a public persona that often appeared to be mischievously knowing, narcissistic, foppish, flippant, pompous and glib.

For all the self-promotion, however, there was never any doubt that regenerating Manchester – in which he included his Salford birthplace – physically and culturally after the grim post-war period was his life’s opus.

A Catholic grammar school boy, he had joined Granada as a reporter after reading English at Jesus College, Cambridge.

In 1975 he was offered a job in London by the BBC, but turned back a few miles from the capital and vowed he’s never leave the north again.

Through the 1980s he had parallel careers in television and the music scene, from which – despite making Factory a global brand and the Hacienda the coolest club on the planet – he made a lot less than a fortune.

But as Manchester boomed in the 1990s, Wilson was one of the prime movers, along with the likes of property developer Tom Bloxham and Simply Red former manager Elliot Rashman, whose opinions mattered in the city and were listened to.

All three were members of what became the “McEnroe Group” – catchphrase “you cannot be serious” – who reacted with disbelief at Marketing Manchester’s fledgling attempts to promote the city in the immediate aftermath of the IRA bomb.

Rashman’s tribute to Wilson when he died of a heart attack, aged 57, following surgery for cancer, is still resonant today: “He selflessly and sometimes shamelessly promoted our city all over the world. Wherever Tony went, he took Manchester with him, proudly championing it like a doting parent.

“There isn’t a PR firm on the planet that could have achieved what Tony did for Manchester. And he did it all for free.”

- This article was last updated 2 months ago.

- It was first published on 9 August 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Celebrating the amazing people taking on Great Manchester Run in 2025

Frankie Lipman steps into Lady Macbeth’s shoes in gutsy new take on Shakespeare

Zeus gets a Salford makeover in this electrifying new play celebrating young creatives

Best bars and pubs to watch the football and live sport in Manchester

Discotheque Royale vs Piccadilly 21s: which was your favourite 90s Manchester club?