Welcome to Manchester – city of culture, protest and an International Festival

- Written by Terry Christian

- Last updated 6 years ago

- Culture

As a native born and bred Mancunian often accused of putting the “er” into Manchester when I talk, I always think of the words of the historian AJP Taylor, who lived and worked in Manchester for a while.

“Manchester is irredeemably ugly, there is no spot to which you could lead a blindfolded stranger and say happily ‘now open your eyes’. Norman Douglas had a theory that English people walked with their eyes on the ground to avoid the excrement of dogs on the pavement. The explanation in Manchester is simpler – they avert their eyes from the ugliness of their surroundings.”

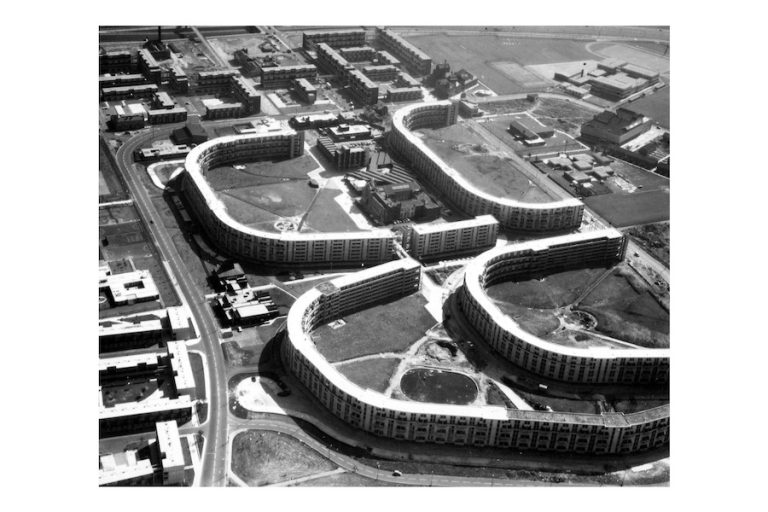

If, like me, you grew up in an inner city area of Manchester in the 1960’s and 70’s you were aware of that. Where we lived didn’t look great – rows of terraced houses in the shadows of blocks of flats. Our comforts were Man United and Man City. I remember as a kid thinking that with United as European champions and City as league champions, I was living in the most famous city in the world.

I was born in Old Trafford, a place – like the football ground, the cricket ground, the industrial park and the shopping centre – named after the Trafford family. One of their ilk, Thomas Trafford, did so much to endear himself to the working people of Manchester as the commander of the Manchester and Salford yeomanry when they made their murderous assault on a peaceful protest of men, women and children at Petersfield in 1819.

Disgracefully, it’s still not to easy to find Petersfield, even though you’re within spitting distance when you come out of Manchester Central.

It was a hugely important moment for democracy and freedom in this country. It led one observer, John Taylor, to found the Manchester Guardian (a paper some of us still stubbornly refer to by its proper name) and Percy Bysshe Shelley to write The Masque of Anarchy with its famous last line, For they are few and we are many.

And it led one of the organisers, leading Manchester radical James Wroe, to come up with the term The Peterloo Massacre, which severely annoyed the Duke Of Wellington by grimly comparing his finest hour at Waterloo to an act of savagery against peaceful citizens.

This is very important to Manchester people. Even if you can’t win, you must – absolutely must – wind up the other side.

It’s nice to know that 11 years later, the workers of Manchester stoned then prime minister Wellington’s train carriage when he turned up for the inauguration of the Manchester –Liverpool railway line, part of which is lovingly reconstructed at the Science and Industry museum.

I know stoning a Tory prime minister’s train carriage is wrong but I can’t help the fact that it still sounds so appealing.

Culturally, let’s face it, Manchester has always been an international and outward looking city.

We had the country’s first professional orchestra and, no doubt, the country’s first professional northerners. We also had the greatest regional TV station – Granada. Its first boss was so determined to keep its northern identity he refused to employ anyone not living in or prepared to travel to Manchester.

God knows if his mantra of “What Manchester sees today, London will see eventually” was true or accurate, but I like its style and boldness. And perhaps there was some justification for it.

Its output included World in Action, whose great work included exposes like the one which led to the freeing of the Birmingham Six First; the first ever coverage of an election on British TV – the Rochdale by-election of 1958; the making of what has been voted the greatest ever documentary – 7 Up (which this year reached 63 Up); and iconic programmes like Coronation Street, Brideshead Revisited and University Challenge.

On the music side, let’s not forget the 1960’s wasn’t just about Liverpool and that whole Merseybeat thing. It was as much Manchester as Liverpool with The Hollies, Herman’s Hermits, Wayne Fontana and The Mindbenders and many more.

Manchester bands were number one in the US billboard charts for six weeks in April and June 1965 – and at numbers 1, 2 and 3 in the USA Billboard Top 100 for one week at the end of April.

And let us not forget the people.

Some say we’re warm. I asked a Mancunian mate if he thought this is true. His reply? “Yeah, but then so is a freshly minted dog turd”.

And then there’s ‘the gritty northerner’. I have never quite worked that one out and I don’t trust it. I think its a southern way of implying we’re a bunch of savages who don’t feel the cold or pain, drink too much, are often quite misogynistic and communicate mainly by grunting. Basically the whole region viewed as one enormous Rugby League team.

Notwithstanding AJP Taylor’s remarks about the ugliness of the geography and architecture, when Manchester people are talking about the city, you may hear them say say “It’s a so much better place since the IRA blew the heart out of it”.

It’s not that they really think acts of terrorism are an acceptable driver of urban regeneration. It just happens that in this case it’s true.

By the way, the Manchester bomb was the biggest ever detonated on mainland Britain – not that you would suspect it from coverage at the time. To his eternal shame, then prime minister John Major didn’t even bother to visit the city. He was probably too scared after what happened to the Duke of Wellington.

So as the Manchester International Festival unfolds, try and enjoy it, point tourists in the right direction and remember our legacy – a legacy we built ourselves. There’s no harm in loving that.

- This article was last updated 6 years ago.

- It was first published on 28 June 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Review: Mariupol Drama at HOME is ‘a harrowing tale of survival, defiance and hope’

Is this the most ambitious regeneration project in Manchester’s history?

When CHANEL rocked “effervescent” Manchester with mind-blowing fashion show