The failed utopian housing project that became a bohemian counterculture ‘paradise’

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 3 months ago

- City of Manchester, Featured, History

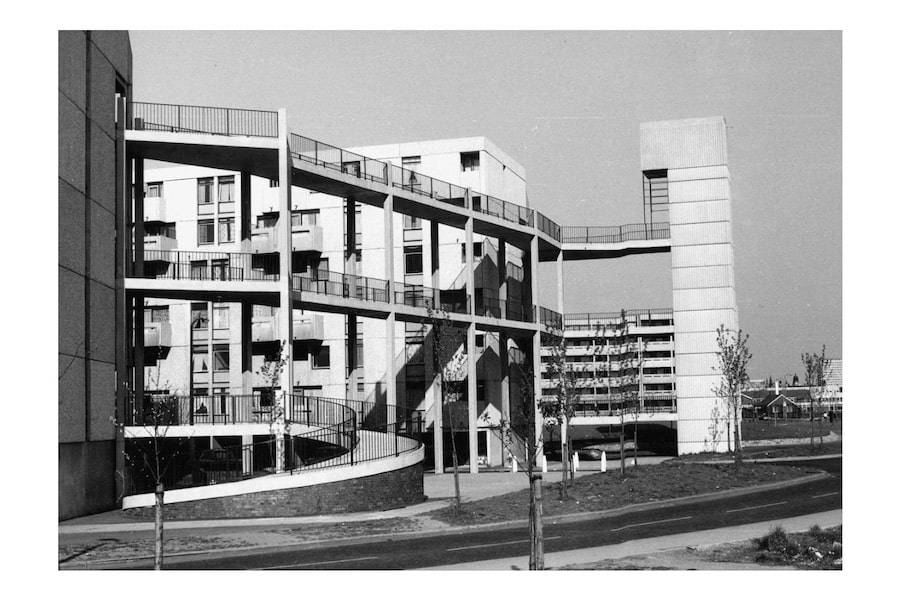

When Hulme Crescents opened in Manchester in 1972, they were heralded as a bold reimagining of urban living.

Designed by renowned architects Hugh Wilson and J. Lewis Womersley, the estate promised to marry the grandeur of Georgian crescents with the efficiency of modernist housing.

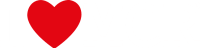

Stretching across four crescent-shaped blocks—each named after celebrated architects Nash, Barry, Kent, and Adam—the Crescents were the largest public housing development in Europe, with 3,284 deck-access homes intended to accommodate over 13,000 residents.

Yet, within just a few years, the Crescents fell from grace, turning from a beacon of hope into one of Britain’s most infamous housing failures.

Despite the cracks in its façade, Hulme Crescents also became a canvas for creativity, rebellion, and cultural reinvention. Its story is one of contrasts—between failure and resilience, desolation and artistic flourishing, alienation and community.

Hulme Crescents

The Hulme Crescents were born out of post-war Manchester’s desire to rejuvenate itself. By the 1960s, Hulme had become a neglected industrial area, dominated by rows of Victorian slums.

The Manchester Corporation’s 1945 development plan described the district as offering “no gardens, no parks, no community buildings, no hope.” In response, city planners turned to the fashionable “streets in the sky” concept, an architectural movement designed to bring high-density, car-free living to cities while preserving a sense of community.

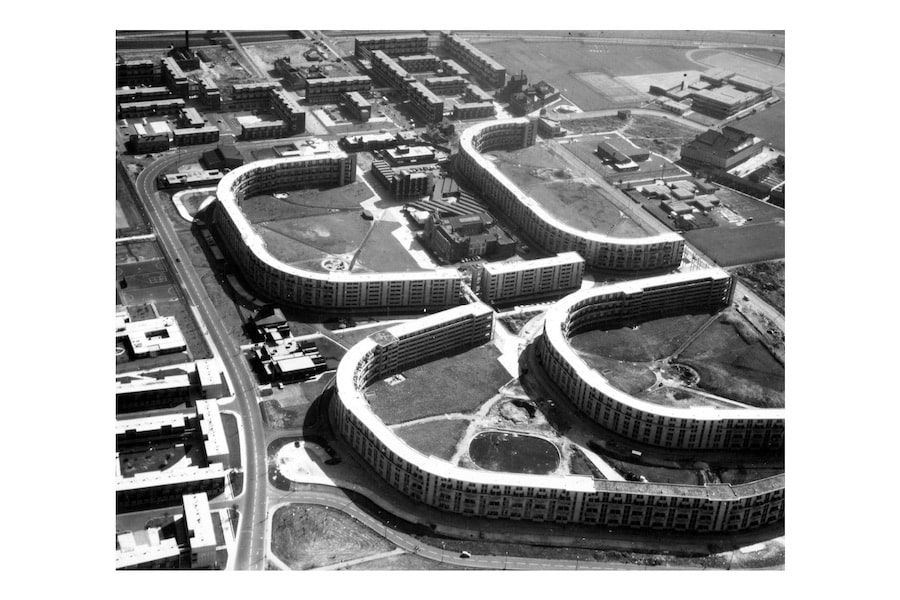

The Crescents incorporated modernist principles with an air of historic grandeur. Kitchens and dining areas overlooked wide, concrete walkways designed for casual encounters, children’s play, and even milk floats. Beneath the walkways, landscaped communal areas were planned to offer green space and shield residents from traffic noise. With private balconies, flat roofs for potential recreation, and integrated shops and amenities, the Crescents aimed to create a self-contained urban utopia.

Womersley envisioned Hulme as a contemporary response to the elegant crescents of Bath and London, but even at the planning stage, the ambitions felt uneasy against the realities of mass housing construction.

The project was built using prefabricated concrete panels, hastily assembled to meet pressing housing demands. These cost-saving measures, combined with rushed timelines, set the stage for disaster.

What went wrong with the Hulme Crescents?

From the beginning, Hulme Crescents were beset by issues. Flaws in design, compounded by poor construction, created an inhospitable environment.

Thick concrete walls trapped dampness, balconies were ill-suited for social interaction, and communal areas felt sterile and unwelcoming. Most dangerously, the structures were riddled with design flaws.

Narrow apertures on balconies, intended to enhance privacy, became climbing hazards for children. Tragically, in 1974, just two years after opening, a five-year-old child fell to their death—a moment that cemented the Crescents’ reputation as unsafe.

Inside, residents faced other frustrations. Underfloor heating—an experimental technology at the time—proved prohibitively expensive to run after the 1973 oil crisis, leaving flats cold and uninviting.

The communal heating ducts became highways for pests; cockroaches and mice flourished in the warmth, while the estate’s damp conditions exacerbated infestations. The Crescents quickly earned notoriety for their pervasive sense of decay, described by The Guardian as a “morass of design faults and tenants’ revulsion.”

By 1975, 96% of residents expressed a desire to leave. Families were gradually rehoused, and by the early 1980s, Hulme Crescents had been largely abandoned by Manchester City Council, which no longer collected rents. For the city’s planners, the Crescents symbolised a monumental failure, but for others, this period of abandonment was the start of something remarkable.

A bohemian rebirth

As the Crescents emptied, a new wave of residents began to populate its crumbling structures: artists, musicians, students, and squatters seeking refuge in its cheap and overlooked spaces.

In this decay, creativity thrived. By the mid-1980s, Hulme had become a haven for Manchester’s bohemian underground, an anarchic and free-spirited community that reshaped the estate into a cultural crucible.

Graffiti transformed the estate’s grey, oppressive walls into vibrant canvases. A group of residents knocked through three flats to create “The Kitchen,” a DIY recording studio and late-night club that drew aspiring musicians, DJs, and artists.

Described as “wild” and raw, The Kitchen became central to Manchester’s burgeoning Madchester music scene, providing a grittier, more authentic alternative to the city’s iconic Haçienda nightclub. Legendary bands like Joy Division, The Smiths, and Simply Red found inspiration in Hulme’s desolation and vibrancy, and the estate’s reputation as an artistic haven grew.

Residents embraced Hulme’s chaotic, countercultural spirit. Flats became stages for impromptu performances and underground raves, while communal areas buzzed with graffiti artists and political activists. For many, Hulme’s decay was an invitation to create—to reclaim a failed urban utopia as their own.

Life on the edge

This bohemian renaissance, however, came at a cost. Poverty, crime, and violence remained pervasive in Hulme Crescents. The labyrinthine walkways and sprawling decks, initially designed to connect neighbours, became corridors of fear, often patrolled only by opportunistic burglars. Residents like Mick Hucknall of Simply Red slept with weapons for protection, while others, like film critic Mark Kermode, resorted to installing reinforced doors—only to have them stolen.

Yet despite its dangers, the Crescents inspired fierce loyalty among their eclectic inhabitants. For many, it was a space of freedom and possibility that stood in stark contrast to the sanitised, commercialised urban renewal projects that would follow. As writer Owen Hatherley noted, “The very fact that so many spaces were unused… led to a sense of possibility absent from the sewn-up, high-rent city of today.”

The end of Hulme Crescents

By the early 1990s, the writing was on the wall. Hulme Crescents were no longer tenable as housing, and the council received £31 million from the government to redevelop the area. Between 1993 and 1995, the Crescents were demolished, their concrete shells reduced to rubble. In their place, a mix of traditional terraced housing and low-rise apartments rose, designed with input from former residents to prioritise liveability over ambition.

For some, the demolition of the Crescents was a relief—a chance to erase a painful chapter in Manchester’s history. For others, it marked the end of a unique cultural moment. While Hulme’s redevelopment brought new stability, it also erased the freedom and creative spirit that had defined the Crescents in their final years.

A mixed legacy

Today, the story of Hulme Crescents remains a polarising one. For architects and planners, it serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of utopian urbanism and the disconnect between design and lived experience.

For Manchester’s artists, musicians, and dreamers, it represents a fleeting era of possibility—a time when even in failure, something remarkable could emerge.

- This article was last updated 3 months ago.

- It was first published on 25 November 2024 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Dear England heads to LOWRY with a story that goes well beyond football

Review: Toxic at Lowry is ‘a raw and unfiltered dive into love and trauma’

The picture-perfect walks in historic places that matter near Manchester