An interview with Manchester dance music producer and pioneer Mark Reeder

- Written by Emily Oldfield

- Last updated 7 years ago

- City of Manchester, Music

You may not have heard of Mark Reeder, but you’ve probably heard his music.

Born in 1958 and raised in Manchester, little did anyone think back in the 1970s that the local lad who worked in the Manchester city centre store of Virgin Records would go onto become an acclaimed musician and record producer.

In a career spread over three decades creating, producing, composing, and remixing, he has worked with the likes of artists including van Dyk, Inspiral Carpets and New Order. He’s even tried his hand at acting.

It was here where he started out, forming punk band The Frantic Elevators with Mick Hucknall and Neil Moss in early 1977. But it was in Germany, where he worked from 1978, that he made it even bigger, founding the dance music labels MFS and Flesh.

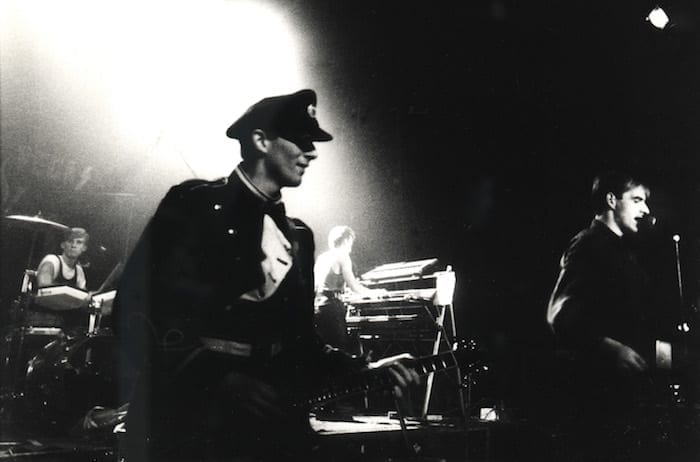

He became Factory Records’ German representative, formed the synthpop-rock duo Die Unbekannten, toured western Europe with New Order and, controversially, brought the Dusseldorf band Die Toten Hosen to play in the East during the 80s.

His remixes have been particularly well known. He’s worked with the likes of the Pet Shop Boys and Sam Taylor-Wood and recently he’s been working with Manchester musical collective Modern Family Unit and remixing their track Law.

He has been described as a godfather of early electronic music and his influence on Manchester was celebrated in the opening music to Manchester International Festival 2017.

And now Mark Reeder is returning to Manchester from Berlin to DJ at an exclusive gig at Tiger Lounge on 5th August. It will be an exclusive opportunity to hear his latest album Mauerstadt, featuring remixes of artists including New Order and Queen of Hearts.

This is one of the last chances you have to see a gig at this authentic venue. It’s due to close in its current venue on 12th August 2017

We spoke to Mark ahead of the gig.

Has this city influenced your work?

Without doubt it has. Growing up in Manchester influenced all my music in one way or another. Dragged around the record stores with my older cousin I got to hear it all.

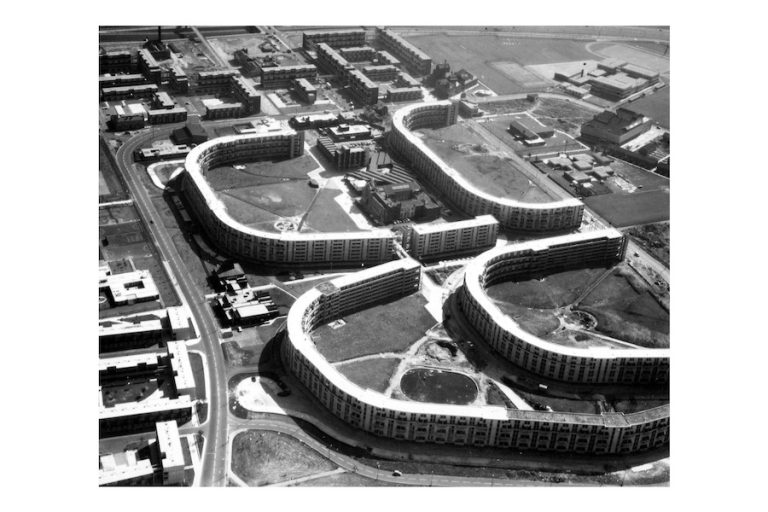

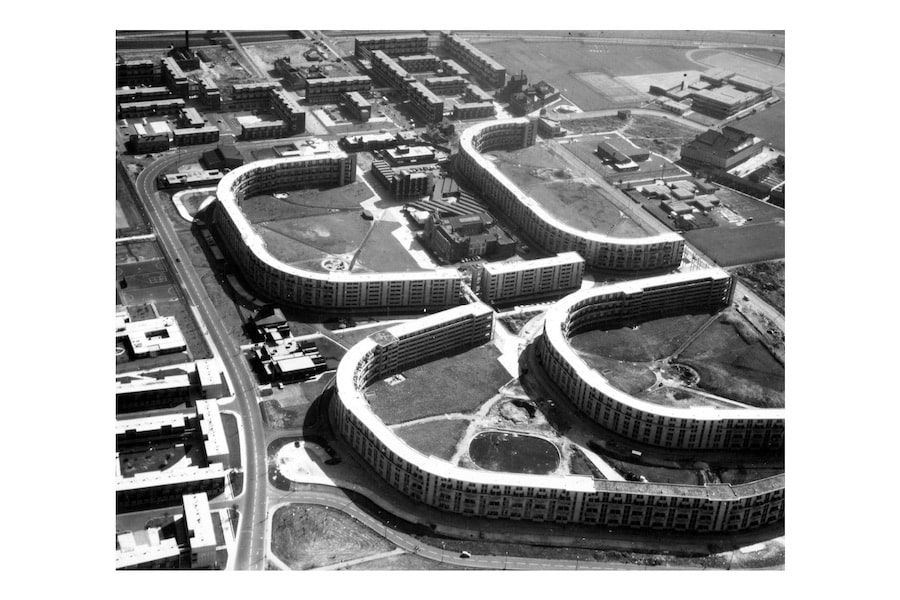

Manchester of the 60s and 70s was a very gloomy, grimy and frustrated place and it reflected on the music produced in the city. A lot of people were unemployed and most made music in the hope they could escape the city and the boredom. After my first trip to mainland Europe, I too wanted to escape.

Musically though, those formative years obviously influenced me, especially as a teenager. I feel very privileged to have lived in this particular era of pop music where everything was possible and everything was new.

Although I have lived in Berlin for 40 years, I still return to my motherland of Manchester a few times a year to see my family and friends and it’s also nice to see how Manchester has changed and keeps transforming.

It has become a very cosmopolitan city with a really positive vibe. I like being a tourist in my hometown, there’s so much to rediscover.

How did working at the Virgin Records Store in Manchester influence your taste in music?

I worked at Virgin Records and Tapes on Lever Street from being a teenager. It was a tiny little shop. This shop was my mecca.

Although I knew all the other record shops in Manchester since being a small child, Virgin then was a new shop and all the people who worked there I thought were super cool and helpful and they would let you hang out there all day listening to records. The shop usually smelt of incense, to cover up the smell of the grass being smoked in the back room. It had a very laid back atmosphere.

The manager of the store noticed I was there every weekend and very well informed for a teenager and eventually he asked me to help them out, I got paid in records at first – I would have spent my wages on records anyway – then I got paid a proper wage and still got free records. In the end, after kicking my job at an advertising design studio, I went to work at Virgin full time.

I met a lot of musicians and arty people there. TV presenter Tony Wilson was a regular customer as was Rob Gretton, who was the DJ at Rafters and Pips Disco. It was a very influential experience. Working in the shop exposed me to all kinds of music that I might never have listened to otherwise. I was forced to endure stuff like The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac and Little Feat or free jazz.

So you can imagine my relief when one day a brilliant single called New Rose was released. It said everything for me. The initial hostile reaction was overwhelming. The hippies in the shop utterly loathed it. I loved to see this reaction and so I played it to death.

Then suddenly, it seemed everything went punk. Virgin was really the only shop in Manchester that dared to sell it – the record shop in the underground market off Market Street sold some punk – but we became punk mecca. That changed everything for the shop and Virgin.

It’s very sad to see the decline of the record shops in most of the world’s big cities, because I think a town without a record shop is something quite depressing. Every town should have at least one, even if it only sells secondhand records.”

Do you have any standout memories of the Frantic Elevators?

There are many. Mick I knew from art college. We had previously both played in a group called Joe Stalin’s Radio Band but not at the same time. I left, he joined.

One night after going to a small gig, he told me he’d seen the future and asked me if I wanted to form a band with him and our mutual friend Moey. I would play bass. I think they probably only wanted me to be in the band because I had a guitar that Moey could use and I worked in a record shop with close ties. They chose the name. Moey because he said he liked the manicness of the word frantic and Mick because he liked the uplifting element to elevators. I quite liked the bizarre visual impression of elevators going madly up and down.

We practised in Broomstair Working Men’s Club, near the knacker’s yard. Outside it stank of glue and inside the place reeked of the previous evening’s beer and fags. It was quite daunting, especially if you had been out the night before yourself.

Songs were usually written in Moey or Mick’s bedroom on an acoustic guitar and we travelled to gigs in a Ford Transit that seemed to just guzzle petrol. I think we only played to pay for the petrol.

I remember once, we had a gig supporting Sham 69 at Rafters. Their sound engineer wouldn’t let us go anywhere near the mixing desk, which meant we would have no outfront sound, only from the backline. In reality it was extortion, disguised as a ransom. We had no choice but to pay him £25 to let us go through their PA (a lot considering the average weekly wage was £42 then). I wasn’t impressed by this collegiality.

Why did you decide to move to Germany?

I actually didn’t decide to move to Germany. I just went there and ended up in Berlin and stayed. Nothing planned. I hitched it to Berlin in the middle of a very drizzly night. No budget airlines back then. I was fascinated by the city and the more I delved into it, the more fascinating it became. Especially after going into communist East Berlin. I knew there was more to discover in the east.

My first Berlin band was called Die Unbekannten (it means the unknown). We didn’t think of this name. It was accidentally given to us by a journalist, who wrote a very positive review of our first disastrous gig in SO36 for a local magazine.

After that, all our Berlin friends called us Die Unbekannten and the name just stuck.

We decided to change our bandname to Shark Vegas when we got the opportunity to go on a European tour with New Order and under that name we released one 12” called You Hurt Me on Factory.

What was it like touring with New Order?

Great! We blew them off stage every night. Naturally, they tried everything to sabotage our gigs.

The crew tried gaffer-taping my arms to my body during an on-stage instrument changeover, in the hope I’d miss my cue, or they’d disarm my amp by removing the fuses and such antics. They would try to demoralise us at every opportunity or tire us out by playing five-aside football during our soundcheck.

“It wasn’t malicious, just the way we Mancs are. Any opportunity to play a trick, or take the piss was never missed. We had great fun.

Rob (Gretton) would be constantly betting people to do the most insane things. Like betting Bernard a £100 to pull down his trousers in this very fancy club full of snotty Swiss rich kids – and Bernard never wore underpants on tour.

Standing on my table, in this fashionable Swiss disco, he apologized for his disgraceful actions. We immediately all got thrown out of the club.

Then during a few days off, we went to Conny Plank’s studio to record You Hurt Me. That was a total disaster too. Conny just played table tennis with his kid’s mates and the sound engineer was suffering from a slipped disc and had to shout his instructions from a camp bed lying in front of the mixing desk. The result was dreadful. In the end, we went back to Manchester to finish it.

Is there something about Manchester sound which attracts you or do you not think it is a location specific thing?

It’s not really the location at all. It just happens to be so. Dave Haslam introduced me to MFU and I liked the guys. They asked me if I would do a remix of Mmm Mmm Mmm Ahhh as I really liked their song. Martyn Walsh and the lads from Inspiral Carpets I’ve known since the early 90s.

As for New Order, they are also very old friends too. They liked the work I did for Bad Lieutenant (Bernard Sumner’s solo project) and so they asked me to choose a track off Music Complete to remix, so I chose Academic, then they asked me to remix Singularity for which they used some footage from my B-Movie (Lust & Sound) for their video.”

You describe your latest album Mauerstadt as ‘an album to break down barriers to’. What do you mean by this?

I actually mean those barriers inside your head, not just real physical ones. Right now, it seems so easy for people to hate, separate and discriminate. They can do it violently and physically, or do it anonymously online, hiding behind a screen.

After the fall of the wall, the future was unity. Sadly, division is fashionable again, and building big walls seems like it’s fashionable again too. The idea that a wall will keep your enemies out and protect and defend you is archaic and very 20th century. We should be trying to solve our problems together in the 21st century instead of creating more.

What can people expect of the material you will be playing at Tiger Lounge?

I always play my own work, with a few exceptions. I treat it more like a gig. So there are slow bits and fast bits. I will be playing many tracks the audience has probably never heard before and some they will probably know, but not in the guise I have made them.”

Tickets are still available for Mark Reeder, featuring Modern Family Unit, at Tiger Lounge.

- This article was last updated 7 years ago.

- It was first published on 28 July 2017 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Community rallies for family after the heartbreaking loss of their daughter

“We’re at breaking point” iconic Manchester bar owner speaks out on hospitality crisis

When CHANEL rocked “effervescent” Manchester with mind-blowing fashion show