Meet the Whalley Range photojournalist whose pictures help save lives around the world

- Written by Louise Rhind-Tutt

- Last updated 3 years ago

- Charity, City of Manchester, Community, People

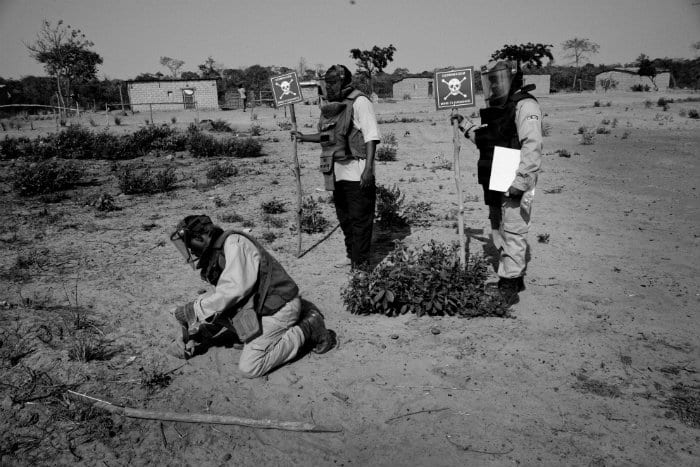

The Manchester-based charity Mines Advisory Group (MAG) is a global humanitarian organisation that finds, removes and destroys landmines, cluster munitions and unexploded bombs from places affected by conflict.

Since 1989, they’ve helped over 18 million people in 68 countries rebuild their lives after war.

Whalley Range photojournalist Sean Sutton has worked for MAG, which was a joint winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997, for more than 20 years, documenting the damage that landmines do and how the work of MAG helps communities recover after conflict.

But for Sean it’s not just about telling stories through his photos. It’s about exposing injustice and the chance to make a real difference to people’s lives.

Sean spent a lot of time travelling and taking photos when he was younger, he says. But it was becoming aware of a situation involving refugees in Thailand that made him want to document the issues arising from conflict.

“I became fascinated by what had happened, the injustice,” he says. “I’d never heard of this conflict going on for so long. And so I was drawn to tell that story. That was my foundation course in photojournalism, really.”

Sean covered the breakup of the former Yugoslavia as well as Cambodia and the conflict of the Khmer Rouge. Landmines were “always part of the narrative,” he says.

“I decided very early on that when I was on assignment somewhere I would try and do something on the landmine issue. Through that I got to know actors involved, including MAG, and one day they asked me to work directly for them.

“I decided very early on that when I was on assignment somewhere I would try and do something on the landmine issue. Through that I got to know actors involved, including MAG, and one day they asked me to work directly for them.

“It was an extraordinary opportunity to use my storytelling through pictures to try and make a difference.”

Sean started working with the Mines Advisory Group in 1995 and became staff in 1997. Has the job changed over the decades?

“The narrative is always changing and it’s always very varied, and my role has always been to try and put the issue involving land mines in context, whether that’s people fleeing from conflict or returning when the guns have fallen silent,” he says.

Sean met Princess Diana in 1997 while she was raising awareness of landmines, and more recently he met Prince Harry, who was continuing his mother’s work by supporting minefield clearance in Angola and who called landmines an “unhealed scar of war”.

“I spent time with her talking through pictures in an exhibition in the Royal Geographical Society, shortly before she died. I told her the stories behind my pictures,” he says about meeting Diana.

“And then exactly a month ago, I had the amazing honour of being asked by the Palace to photograph Prince Harry. It was amazing to see him following in his mother’s footsteps and highlighting the issues around landmines. It was very poignant.”

Angola, where MAG has worked for 25 years, is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world. Forty years of conflict from 1961 to 2002 left the country strewn with an estimated one million landmines and many more unexploded bombs.

“In Angola you still have this ongoing crisis after all these years. The collapse of the economy means there are fewer jobs and people are moving back to their ancestral lands. But those areas are full of mines,” explains Sean.

“The fear around landmines is impossible to imagine.”

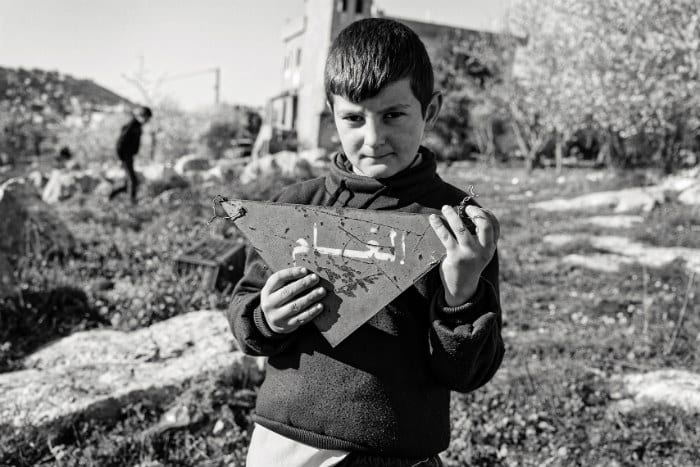

Every day, 20 people are reported killed or injured by landmines and unexploded bombs globally. Almost half of the civilian casualties of landmines are children.

The work MAG does, both from its Manchester headquarters and out in the field, is vital, believes Sean.

Earlier this year, on International Landmine Awareness Day (4th April), MAG launched their #HomeSafeHome appeal to help build safer futures for families in Lebanon.

The appeal raised an astounding £317,441 – including £146,185 of matched giving from the UK government and GiftAid. Because of the appeal, in the next few days a landmine clearance team will start work in a heavily-landmined area known as the “Blue Line” southern Lebanon.

For five months the team will work in Meiss Al Jabal to clear 21,000m² of land – directly benefitting 750 women, girls, boys and men who will be able to live in safety.

“People think I’m crazy because I’m going to all these places that people are familiar with from the news for the wrong reasons,” says Sean, who spends a large proportion of his time away from home.

“But in fact rarely do you feel threatened. People are amazing and they’re always very welcoming. I’m very lucky to be able to travel to all these places.”

And when he’s back in the UK, Sean is very happy to call Manchester home, where he’s lived since 1998 and raised his children.

“What I like most about Manchester is the friendliness and openness and frankness of the people,” he says.

“People will tell you what you think, and that’s a good thing. And it’s a fascinating place, too. You have all sides of life represented.

“It’s all exciting and stimulating. It’s a city that feels like it’s going somewhere.”

- This article was last updated 3 years ago.

- It was first published on 1 November 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

How one selfless act sparked a career dedicated to saving lives

Former sheltered housing transformed into safe haven for vulnerable youth

Manchester and Los Angeles prove that opposites really do attract