Uncovering Manchester’s complicated relationship with slavery

- Written by Ed Glinert

- Last updated 2 years ago

- Featured, History

Manchester hugely prospered from the slavery system of the 18th century.

The growing town emerged as the centre of the world cotton industry by capitalising on the raw produce being picked by slaves in America; not just cotton, but sugar as well.

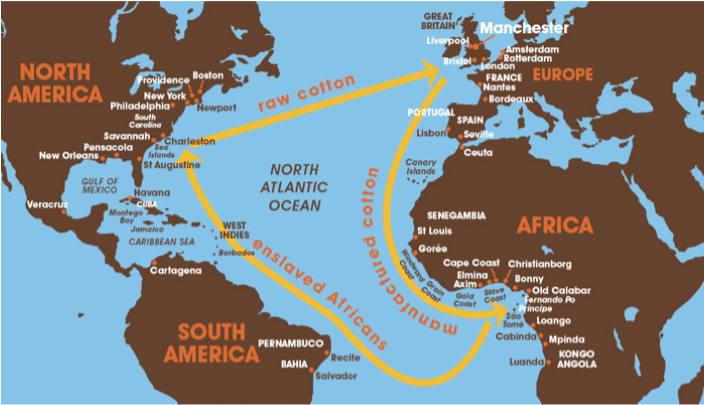

The Slavery Triangle system saw cotton goods and household appliances made in Lancashire, exported to West Africa where they welcomed the loose-fitting clothes, and the pots and pans.

The empty ships were then filled with slaves, picked by the local African gang masters, transporting them to what they used to call “the Brazils”, the Caribbean and the Southern cotton states of America.

The ships then replaced the slaves with cotton and sugar which was sent back to the western ports of Britain.

Prominent Manchester families such as the Hibbert’s owned sugar plantations in Jamaica.

Samuel Touchet imported cotton from the Levant and the West Indies and paid for the invasion of Senegal in 1758.

The Heywood’s dealt in African goods including ivory.

They paid for some 130 slaving voyages from 1745-89.

Interestingly they gave up investing in slavery in the 1780s and went into something more morally acceptable – banking.

Slavery is back in the news, or it never goes away.

Last March, the Guardian miraculously discovered that its founder of 1821, John Edward Taylor, was importing slave-picked cotton.

“The process [of identifying this]…was a lengthy and difficult one. It took two and a half years.”

Come again?

This should have taken several seconds.

Every cotton merchant in Manchester two hundred years ago was benefiting from slave-picked cotton, just like everyone in 2023 Manchester is in some way benefiting from an oil industry which keeps the world in a permanent state of tinder-box politics.

In Taylor’s day, the Lancashire machines were geared up to the Sea Isle staple, cotton grown in the islands off the coast of the Carolinas.

It was said to be the best type of cotton and was picked by slaves until the 1870s.

On Wednesday the 19th of April the Guardian “discovered” that the ship on the Manchester coat of arms, devised in 1842 is a slave ship, something I’ve been explaining on my Manchester tours for fourteen years.

Oh for the days when the Guardian was based in Manchester, staffed by some of the greatest journalists in British history, such as Arthur Ransome and Neville Cardus, and deployed editor-owner C. P. Scott’s clear-minded, clear-sighted national and international outlook.

A better story than that in the Guardian would tell how despite a regrettable 18th-century history of mostly supporting slavery, Manchester, unlike say, Liverpool, was one of the first places to campaign for its abolition.

Many of those who prospered from slavery did what they could to change the system.

That’s worth celebrating, not hiding.

That’s the story.

Just like in Britain over the last forty years, things that were once rebuffed and ostracised are now embraced with equal fervour. Attitudes change very quickly.

Progressive ideas of the day, from the easing of anti-Catholic legislation, the growth of the enlightenment, the new scientific age that replaced old alchemical superstition, the original motives behind the French Revolution took sway along with pressure from the non-conformist Protestant groups, particularly the Quakers, that buoyed the Manchester of that time, into a major U-turn.

In short, Manchester led the fight against slavery.

The leading abolitionist of the time, Thomas Clarkson, described by the poet Samuel Coleridge as a “moral steam engine, founded the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade on the 22nd of May 1787.

Five months later, at the Collegiate Church (now Manchester Cathedral), he spoke to a huge crowd after travelling over 35,000 miles through Britain, mostly on horseback, interviewing 20,000 sailors, collecting artefacts such as leg-shackles, thumbscrews and branding irons to build up the case against slave trading.

He published a plan for the Liverpool slave ship the Brookes showing how 450 slaves were packed inhumanly below the ship’s deck.

Clarkson recalled his talk.

“When I went into the church, it was so full that I could scarcely get to my place; for notice had been publicly given, though I knew nothing of it, that such a discourse would be delivered.

I was surprised also to find a great crowd of black people standing around the pulpit.

There might be forty or fifty of them. The text that I took as the best to be found in such a hurry [Exodus 23:9], was the following: ‘Thou shalt not oppress a stranger, for ye know the heart of a stranger, seeing ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.’”

Following Clarkson’s intervention, a number of anti-slavery organisations were formed in Manchester: The Constitutional Society; the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society; the Emancipation Society; the Manchester Union. In Liverpool, sailors tried to throw Clarkson into the harbour.

In 1795, a 20,000-name petition from Manchester calling for the abolition of slavery was sent to Parliament.

Indeed Manchester had more signatures than that of any other place, but the petition hasn’t survived.

It was lost in a fire that destroyed the Houses of Parliament in 1834.

In 1807 the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act banned the system in Britain.

In 1833, slavery ended in the British colonies.

Politics is a continual battle between illumination and horror, but not everything can be solved instantaneously.

This was the period when the new enlightened generation of Manchester merchants and leaders, men like Manchester Guardian founder Taylor, and the free traders Richard Cobden and John Bright, taking advantage of the ending of slavery in Britain, were now trying to do the same in their great trading partner, America.

Cobden was instrumental in 1838 in the creation of the council so that the people ran Manchester, not the absentee landlords, the Mosley family.

He was one of a group of local leaders who devised a coat of arms for the newly-incorporated Manchester.

They knew that the ship they chose was the same as the ones that took part in the by-now-abandoned Slavery Triangle, but they were clever.

The ship depicted bears resembles the vessel Black Joke.

This had been a Brazilian slave ship, Henriquetta, captured by the Royal Navy in September 1827 and renamed after a well-known song of the day.

Her new role was to chase down slave ships.

She freed thousands of slaves before being scrapped in 1832.

The ship on the Manchester coat of arms is also a symbol of international maritime trade – the free trade system that Cobden and Bright triumphed nationally against the Tory government’s protectionism; trade free of government interference.

It showed how Manchester was now using ex-slave ships for a better system, although in today’s atmosphere, many now believe free trade to be iniquitous, ripe for a campaign of opposition ever since Margaret Thatcher used it as a foundation of her philosophy.

Manchester led this new battle, for free trade.

Cobden and Bright succeeded in 1846 with a change in the law.

It is why we have a Free Trade Hall.

The Guardian’s recent hand-wringing is symptomatic of a modern-day malaise among the Left in Britain centred around an alarming lack of confidence in Britain’s past, an uncertain desire to replace it with enthusiasm for a new story but unsure what that story is.

It’s an ignorance that manifests itself in claiming to be on the right side of history without any understanding of what that history is.

Yes, Manchester participated in slavery…everywhere did.

Yes, Manchester led the fight against slavery.

Not everywhere did.

You can catch Ed Glinert’s next “Manchester and Slavery” FREE tour takes place on Saturday the 27 th of May at 11am from Victoria Station wallmap.

Find out more by clicking here.

The gradual decline of slavery and Manchester’s key role in its passing brought with it some intriguing stories.

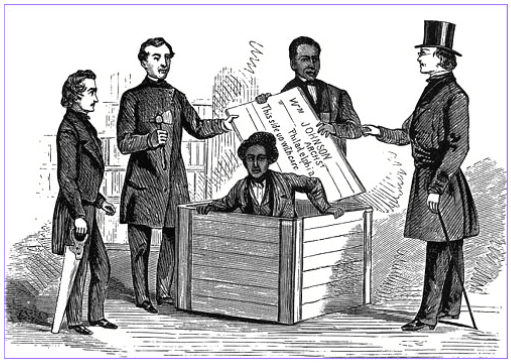

Some former slaves became well known in Manchester. Henry Brown was born in 1815 enslaved on a plantation near Richmond, Virginia.

In 1849, Brown’s master refused to buy Brown’s wife when she and their children were put up for sale, and so they were bought by a man in North Carolina. Brown was determined to escape from slavery and devised an ingenious scheme: he would post himself to Philadelphia in a box!

The 350-mile journey took 27 hours.

In Philadelphia the box was opened and Brown jumped out and declared: “Good morning, gentlemen!”

He went round relating his story, arriving in Liverpool in October 1850 along with Smith, a free black American who had helped him in his escape.

They toured the north of England with an exhibition called “The Mirror of Slavery” and Brown settled locally.

The 1871 census records him living in Cheetham, where he and his wife were doing well enough to employ a servant (sic).

In 1875 he returned to America; his story, The Narrative of the life of Henry ‘Box’ Brown, written by himself, was printed by Lee and Glynn of 8 Cannon Street, Manchester (where Foot Asylum now stands).

- This article was last updated 2 years ago.

- It was first published on 24 April 2023 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Hilton Manchester Deansgate’s superstar chefs shine on the world stage

Stalybridge to get multi-million pound makeover of public spaces

Review: The Engagement Party at Queen Elizabeth Hall ‘is full of immersive fun’

Piehard: where to get the best pies in and around Manchester