Manchester: a city where music still has the power to turn strangers into family

- Written by Dave Haslam

- Last updated 2 months ago

- Culture, Featured, Music, Nightlife

I have an older sister and a younger brother, but for some of my childhood my parents fostered too. This was mostly when I was between about seven and twelve years-old. Social services would phone, and a child, or two siblings, would arrive at our door a few hours later.

In the space of five or six years, around thirty-five foster kids came into our home for anything between a few days and several months.

The kids were from a number of different religions and races, although not quite all ages. My parents had a policy of only accepting kids younger than my younger brother. This was so we didn’t feel displaced by the foster children, but it also had the effect of casting us all in caring roles.

Some of the children were old enough to go to school, and some were babes in arms. My mother was generally a happy person but never happier than when she had a reason to get a babygro out of a drawer for a very young child, and assemble the high chair.

The kids would be temporarily fostered with us for a variety of reasons; sometimes the mother was trying to escape domestic abuse, or the mother was in hospital or in jail (there weren‘t many fathers around). Often we’d host a pair of siblings, and they’d be glued together from the moment they came through the front door.

We’d treat them just like younger brothers and sisters. We would care and look out for them, but we’d also bicker sometimes. They‘d play football or hide-and-seek with us, watch Wacky Races on TV after school, and come on family holidays.

Writing Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor, I considered and celebrated various encounters and influences on my life. Throughout my memoirs I document and celebrate meeting people who made an impression on me; like John Peel, Nile Rodgers, Tony Wilson, and Tracey Thorn.

I also analysed those years fostering for the first time. I was young, at an age when you experience life at face value. Now, though, I understand that I was drawing many lessons from fostering, not least to value my stable family life, but also to appreciate the heavy loads some people have to carry.

I doubt many of my foster brothers and sisters recall their short times with us, although two of them have subsequently taken jobs that have given them access to their social services files and made contact. One recalled just a fleeting image; a day in the countryside, when cows ran across a field to watch us eat a picnic.

The experience of fostering exposed me to the struggles of some families but also helped give birth to a sense of idealism. We’d get home from school, a newly-arrived youngster would be introduced to us and we’d grab them by the hand, show them their bedroom, go find the dressing-up box, or run into the garden.

It was that quick, that simple, that amazing; in thirty seconds the person standing in front of us transformed from a stranger to a sister or a brother.

Writing my book, especially the chapters about DJing in clubs like the Hacienda in the 1980s and 1990s, I became aware how utopian my attitudes to discotheques and dancefloors are. I realised that the encounters with my newly-arrived foster brothers and sisters acted like a precedent, a model for the best kind of interaction with a stranger; immediate acceptance and connection.

Granted, it was a temporary attachment – when they departed I don’t recall ever missing them (I suspect it may have been different for my mother) – but lots of important things in our lives are temporary; love, anger, heartache, a day trip to the countryside. It doesn’t mean they’re not real.

I remember in packed clubs playing a record in 1990 by the Break Boys called My House Is Your House (And Your House Is Mine). I was in the midst of a music scene that was communal and accepting, where people from various neighbourhoods and backgrounds had come together to party.

The music was the attraction and the glue, although by then the positivity was also being fed by the drug ecstasy. But even earlier in the 1980s, before the drug, I’d already enjoyed and seen something special in clubs and venues around Manchester.

Some nightclubs I’d swerved, keen to avoid the pissed-up guys desperate to fight me. At others, mostly small-scale, and midweek places, ad hoc and life-enhancing communities were being formed.

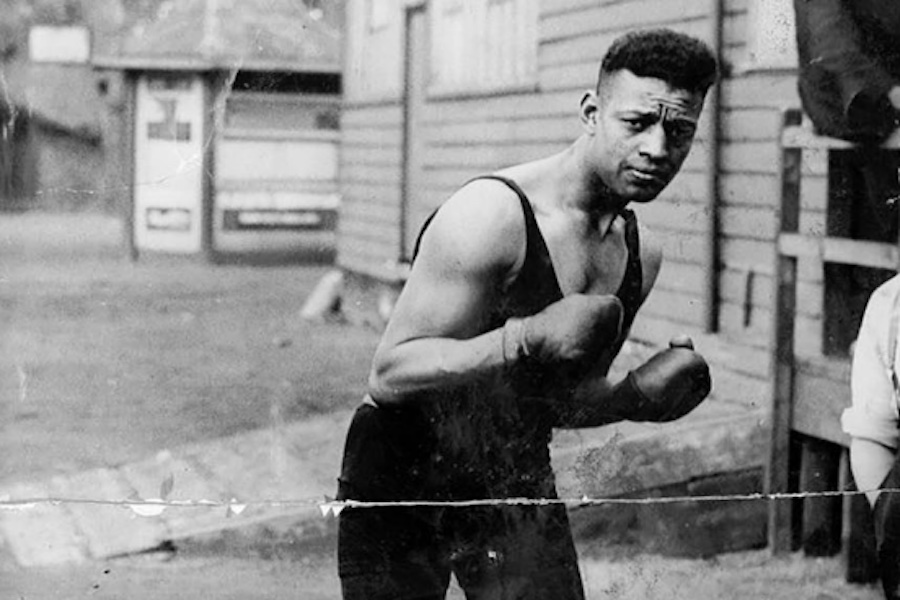

These were places like-minded folk could find escape, connection, life. Twenty-five people dancing to 23 Skidoo at the Man Alive. Hi-energy in close-knit, hardcore gay clubs like the Archway. Electro soul nights at the Reno in Moss Side.

It’s still like this in Manchester, and elsewhere; unheralded little utopias trying to avoid closure at the hands of inept council planners, or rapacious property developers.

And it’s still a joy for me, witnessing it happen; people gather, the music plays, and thirty seconds later strangers are brothers and sisters.

- This article was last updated 2 months ago.

- It was first published on 8 August 2018 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Head down the rabbit hole for Adventures in Wonderland with Z-arts

Major rail investment set to transform Manchester-Leeds commutes

“His presence will be deeply missed” Children’s hospice bids farewell to their visionary CEO

Has Gordon Ramsay created Manchester’s ultimate bottomless brunch?

The Clink celebrates ten years of empowerment and second chances