The story behind the world’s first intercity railway

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 2 months ago

- Cornerstone, History, Museums

Manchester holds a significant place in transportation history as the terminus of one of the world’s first interurban railways, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

This pioneering steam-powered railway was designed to revolutionise the movement of both passengers and goods, and its establishment marked the beginning of a new era in trade and travel.

In the early 19th century, Manchester was a bustling industrial city, its mills powered by the relentless flow of raw cotton arriving from Liverpool. Yet, the journey between these two economic powerhouses was fraught with delays and dangers.

The canals and roads connecting Liverpool and Manchester were not only slow but perilous, with goods often damaged and lives put at risk. It was clear that a revolutionary solution was needed to streamline the transport of goods and passengers between these vital hubs of commerce.

The vision of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The idea of a railway connecting Liverpool and Manchester emerged in response to the booming goods traffic of the 1820s. Liverpool, as the nation’s primary port for raw cotton, fed Manchester’s insatiable mills, which in turn sent finished textiles back to Liverpool for global distribution.

Despite the proximity of these two cities, the journey for goods from New York to Liverpool was often shorter than the subsequent trip from Liverpool to Manchester.

“Goods would arrive in a shorter time from New York to Liverpool than they could afterwards be conveyed from Liverpool to Manchester,” reported The Observer in September 1830. This inefficiency underscored the dire need for a faster, safer alternative to the existing canals and roads.

Enter William James, a visionary land agent and railway enthusiast, who alongside Liverpool merchants Joseph Sanders and Henry Booth, spearheaded the movement to establish a railway. They formed a committee comprising merchants, bankers, engineers, and politicians, laying the groundwork for what would become the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

Surveying the route was no small feat. The proposed railway faced fierce opposition from landowners who did not want the railway to cut through their properties. These landowners went as far as hiring thugs to disrupt the surveyors’ efforts, forcing the surveyors to work under the cover of night to avoid confrontation. Despite these challenges, persistence paid off, and the railway was approved on April 6th, 1826.

Engineer George Stephenson

Engineer George Stephenson, a name now synonymous with railway engineering, was tasked with the monumental challenge of constructing the railway. His team had to overcome significant natural obstacles, including rivers, valleys, and the infamous Chat Moss—a vast bog that threatened to swallow the tracks.

Ingeniously, Stephenson and his team devised a method of floating the tracks on tree trunks and shingle, effectively taming the treacherous terrain. Over four years, they built 63 bridges across Lancashire’s valleys, marking an era of unprecedented engineering achievements. These efforts culminated in a network that not only connected Liverpool and Manchester but also set a new standard for railway construction worldwide.

Construction

The construction of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was a monumental task, facilitated by a series of legislative acts and innovative engineering solutions. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway Acts of 1827, 1828, and 1829 laid the legal groundwork for this ambitious project. The line spanned 31 miles (50 km), with management divided into three sections overseen by Joseph Locke, William Allcard, and John Dixon.

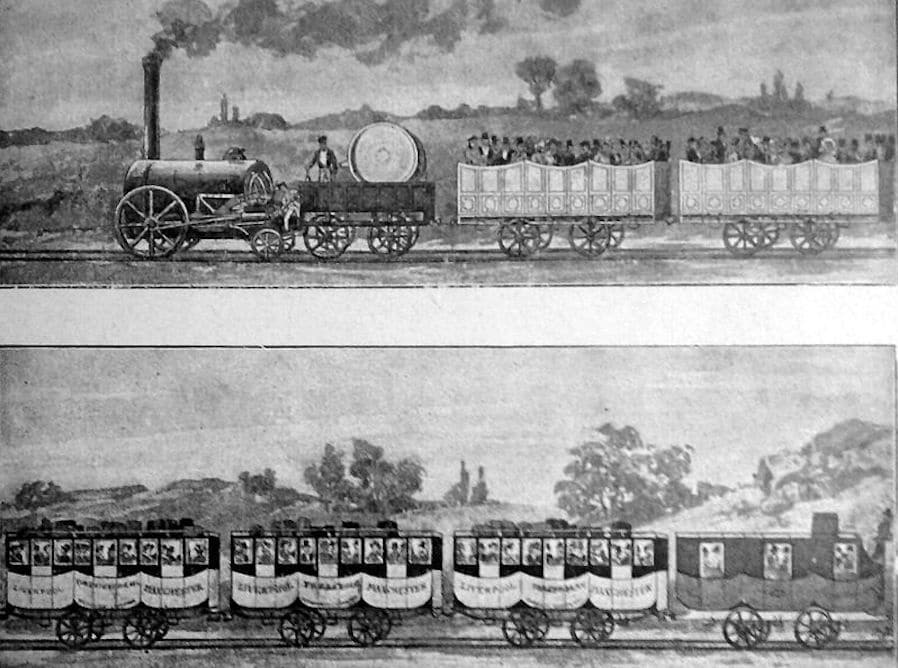

One of the most challenging parts of the construction was the crossing of Chat Moss, a treacherous bog that resisted conventional drainage methods. Engineers adopted a design by Robert Stannard, utilising wrought iron rails supported by timber in a herringbone layout, and an immense amount of spoil was dropped into the bog to stabilise it. On December 28th, 1829, the famous locomotive Rocket successfully crossed Chat Moss, marking a significant milestone in railway engineering.

Other engineering marvels included the 2,250-yard (2.06 km) Wapping Tunnel, the world’s first tunnel bored under a metropolis, and the 2-mile (3 km) long cutting at Olive Mount. The railway also featured the Sankey Viaduct, a nine-arch structure over the Sankey Brook valley, and the innovative cast iron Water Street bridge in Manchester, designed by William Fairbairn and Eaton Hodgkinson. This bridge’s design foreshadowed future developments in railway bridge construction, despite some early catastrophic failures in similar structures.

The railway required 64 bridges and viaducts, mostly constructed from brick or masonry. The track itself was laid using 15-foot (4.6 m) fish-belly rails, either on stone blocks or wooden sleepers, especially over Chat Moss. The physical labor was carried out by “navvies,” who, despite using hand tools, moved impressive amounts of earth daily. The dangerous working conditions led to several recorded deaths, underscoring the perilous nature of early railway construction.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway’s completion represented a groundbreaking achievement in transportation, setting the stage for the global expansion of railway networks and cementing Manchester’s place in industrial history.

The Rainhill Trials

The next challenge was deciding what would power the railway’s carriages. While some advocated for stationary steam engines or even traditional horsepower, George Stephenson championed the steam locomotive. To settle the debate, the directors organised the Rainhill Trials in 1829, a competition inviting engineers to present their locomotive designs.

Five entrants competed: Cycloped, Perseverance, Novelty, Sans Pareil, and the Rocket, designed by George Stephenson’s son, Robert. The trials drew massive crowds, with over 10,000 spectators witnessing the Rocket’s triumph, which ultimately validated the steam locomotive as the future of rail transport. “Communications were received … from professors of philosophy, down to the humblest mechanic, all were zealous in their proffers of assistance,” noted Henry Booth in 1830, highlighting the widespread interest and support for this groundbreaking technology.

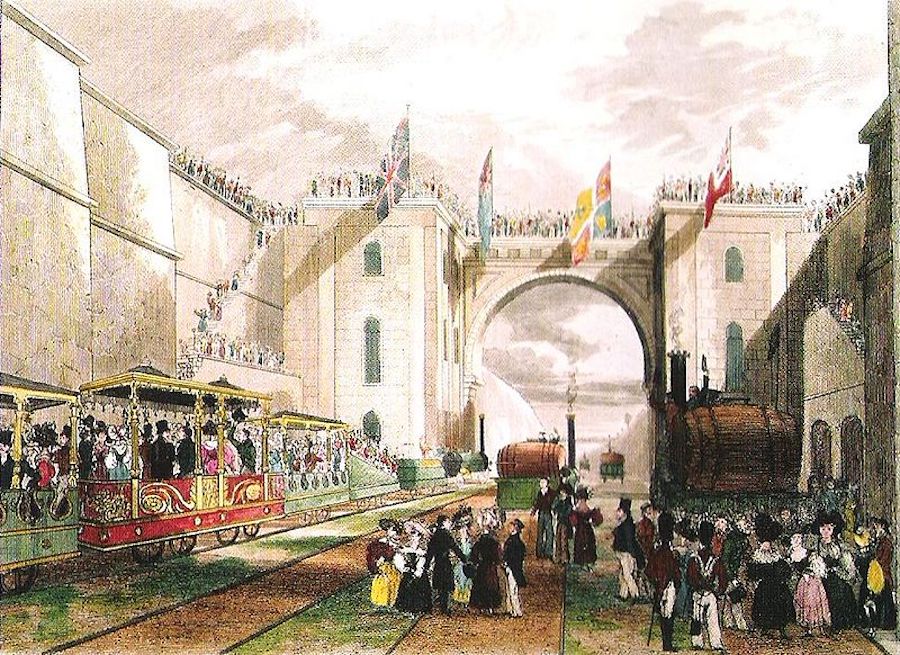

The Grand Opening…and tragedy

The railway officially opened on September 15th, 1830, amidst great fanfare. Dignitaries, including Prime Minister the Duke of Wellington and the Austrian ambassador, participated in the inaugural journey from Liverpool to Manchester. The celebration was marred by tragedy when William Huskisson, MP for Liverpool, was struck by the Rocket during a stop to refuel. His death cast a shadow over the event, but the railway’s momentum was unstoppable.

Despite initial fears that the tragedy might deter potential passengers, the opposite proved true. Railway fever gripped the nation, with thousands eager to experience this new mode of transport.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway quickly exceeded expectations, with passenger numbers soaring from an anticipated 250 per day to 1,200 within the first month.

Liverpool Road Station

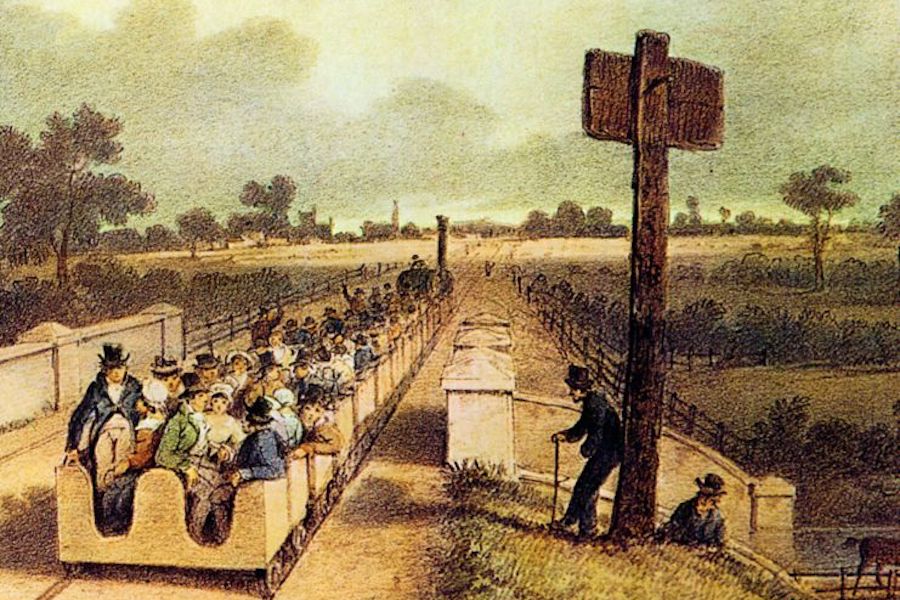

The creation of Liverpool Road Station, the world’s first railway station for both passengers and goods, was a pioneering effort in itself. Architect David Bellhouse Jr. drew inspiration from local canal warehouses to design a facility capable of handling diverse cargo, from cotton to coal and bananas to butter. First-class passengers enjoyed the luxury of enclosed carriages with upholstered seats, while second-class travellers had to endure less comfort, reflecting the class distinctions of the era.

Before the advent of the railway, most people had never travelled faster than a horse could carry them. The railway transformed this, offering speeds twice that of stagecoaches at half the cost. It revolutionised not just transportation but also communication, with trains rapidly delivering newspapers and mail, thereby spreading information and ideas more efficiently than ever before.

The railway’s impact on the local economy was profound. It boosted Manchester’s growth as a manufacturing centre, facilitating faster and more reliable transport of goods. By 1844, the original Liverpool Road Station had transitioned to handling goods exclusively, as passenger traffic shifted to the newly constructed Hunt’s Bank—later known as Victoria Station, which remains a crucial hub in Manchester’s transport network today.

A blueprint for the world

The success of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway did not go unnoticed. It became a model for railway construction worldwide. Between 1830 and 1845, a period known as “Railway Mania” saw over 35 new railway lines spring up across Britain, all inspired by this pioneering line. The influence of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway extended far beyond Britain’s borders, setting a standard that would shape global railway development for decades to come.

Historical significance

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway’s opening in 1830 marked a significant milestone in the history of rail transportation. It was not merely an engineering marvel but also a groundbreaking advance in railway operations, offering regular commercial passenger and freight services powered by steam locomotives. This railway’s speed and reliability set a new standard, eclipsing the previous horse-drawn carriages and earlier locomotive experiments.

The L&MR became a model for other railway companies, influencing the development of subsequent rail lines both in Britain and internationally. Some have even claimed it to be the first inter-city railway, though the term ‘inter-city’ emerged much later, and neither Liverpool nor Manchester held city status at the time of the railway’s inauguration. Regardless, the 31-mile distance between the two towns was substantial enough to demonstrate the railway’s potential for long-distance travel and commerce.

Another lasting legacy of the L&MR is the standard gauge of 4 ft 8½ in (1,435 mm), which became the universal track gauge for railways around the world. This decision was made in a board meeting in July 1826, aligning with the gauge used on the Darlington Road and allowing for compatibility with the Stephensons’ testing facilities in Newcastle.

The railway’s operational norms, such as left-hand running and the adoption of a coupling system with buffers, hooks, and chains, established practices that were adopted throughout Europe and beyond. The rapid expansion of railway networks that followed the L&MR’s success underscored its influence and the essential role it played in ushering in the railway age.

So, another world first for Manchester. It just goes to showcase the city’s innovative spirit and industrial prowess.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway not only revolutionised transportation and trade but also laid the foundation for the modern railway systems we rely on today.

As we reflect on this monumental achievement, it’s clear that the legacy of those early railway pioneers continues to shape our world in ways they could scarcely have imagined.

- This article was last updated 2 months ago.

- It was first published on 21 January 2025 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Review: Tambo & Bones at HOME is ‘ambitious, bold, gutsy…. and terrific’

Review: JB Shorts 26 at 53two is ‘a five-star showcase of northern talent’