Liverpool and Manchester: why we should be friends with the city down the road

- Written by Dave Haslam

- Last updated 3 months ago

- Cornerstone, Culture, Sport

My first impressions of Liverpool weren’t great. I was 19. I stepped off the train at Lime Street station and walked towards the city centre. There was an underpass from the station to where the Holiday Inn now stands. As I entered the underpass I saw a woman crouching at the far end. I realised she was having a piss. It was 10.30 in the morning.

The second time I went to the city, before getting the train home to Manchester I idled away twenty minutes in a pub near the station. Fellas kept approaching me offering items for sale. The most persistent young man tried to sell me a pair of trainers. He said they were made by Lacoste.

So first impressions: a woman pissing in the underpass, a scally trying to sell me cheap Lacoste. But you know what? Liverpool is now one of my favourite cities in the world.

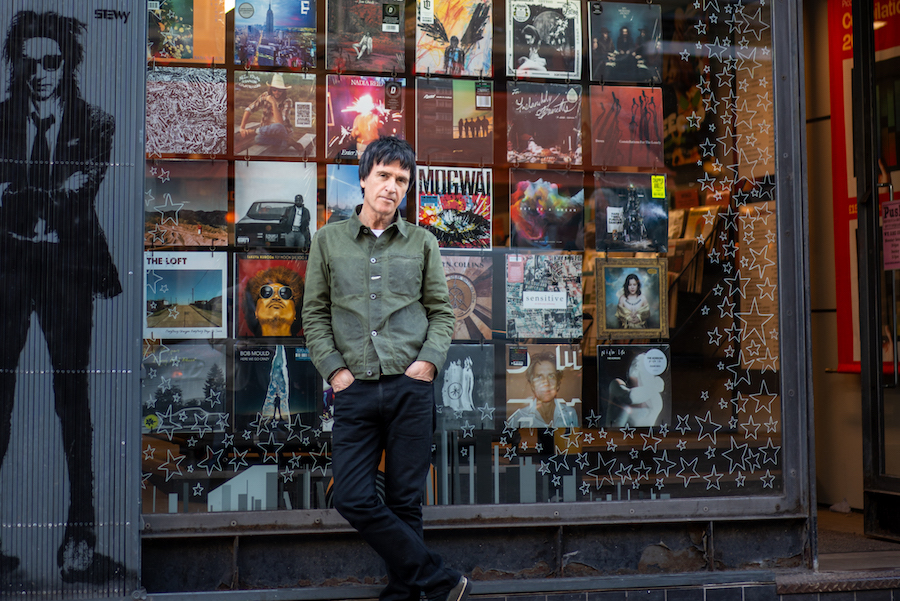

I found a tribe over there I loved a music community. Pete Wylie was, and remains, tremendous company. My first visit to Liverpool was to meet him. He was in a band called Wah Heat who had just released their first album. Wylie showed me his favourite haunts – Probe Records and a venue called Eric’s where Roger Eagle booked bands.

In 1978, Tony Wilson established regular Factory nights with Alan Erasmus at a club called the Russell in Hulme. Factory later became a record label, of course. Such was the reputation of Eric’s, Tony asked Roger Eagle to have a hand in booking acts at Factory nights.

A year or so later, Tony made an alliance with the Liverpool label Zoo and together they organised a music festival in Leigh featuring bands including Joy Division and Echo & The Bunnymen.

The Supersonic documentary currently showing in cinemas includes Noel Gallagher talking about the importance of the Liverpool band The Real People on Oasis’s career. Elsewhere, improbably, but generously, he has described watching Cast as being like a ‘religious experience’.

In direct contrast to all this mutual respect and collaboration, on Monday evening we’ll once again witness fans of Liverpool and Manchester United locked in conflict. It’s very unlikely there won’t be chants about Munich from one side and about Hillsborough from the other.

Most football fans are embarrassed by the very small minority that indulge in this hate. Watching football should always have an edge and it’s a huge adrenalin rush when your team defeats its most bitter rivals, but the Munich/Hillsborough stuff is something else.

I love Wylie and his tribe and I have been lucky enough to see the emergence of younger Liverpool music generations, too. The crew behind Cream, the Sound City team, and the organisers of Liverpool Psyche Fest. Liverpool has other attractions for culture connoisseurs including the Tate and FACT.

Instead of giving London the satisfaction of seeing two neighbouring northern cities scrapping, I suggest that the cities should work together and, with both suffering the effects of austerity policies, there’s plenty of common ground.

I applaud loyalty to the place where you were born grew up or lived. But does this loyalty have to spill into disrespect for people in other places? It’s weird to hate people because they live in a house much like yours with a family much like yours, but thirty-five miles away. Or even less if you’re talking Burnley and Blackburn or Newcastle and Sunderland.

This need to show your allegiance to a town or city by disrespecting other places shares the mindset of the xenophobes -people who can’t make a distinction between pride in your country and hostility to others.

You can’t pour scorn on the Munich/Hillsborough chanters without acknowledging that in our public discourse, on social media, in the world of Donald Trump, in the tabloids, and in Westminster, being small-minded and in a rage is all the rage.

What is it in our collective psyche? It’s like politicians and commentators have taken their cue from the most senseless football fans. On social media, the Corbyn re-election revealed vicious Us versus Them attitudes. Meanwhile, UKIP types threatened by croissants and intolerant of dark-skinned people are popping up everywhere, emboldened by Brexit. Xenophobia now seems to have a major role in government policy.

It’s like some people can’t exist without creating an enemy. I’m a citizen of the world. I don’t get the need to denigrate other countries.

When there are voices so loudly and mendaciously exaggerating divisions, we can kick back by stressing the common ground between us and the town on the other side of the hill, the people and the country across the border, the city down the road.

- This article was last updated 3 months ago.

- It was first published on 11 October 2016 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

The Manc aerobics queen who trained the Corrie cast is helping raise charity cash

Ancoats to get even cooler as independent market set for MOT garage site

“Manchester is not Britain’s second city, it’s the first” – Jeremy Clarkson