100 years since The Representation of the People Act – and why Manchester matters

- Written by Emily Oldfield

- Last updated 7 years ago

- City of Manchester, History, Museums, People, Sport

Today marks 100 years since the Representation of the People Act was passed on the 6 February 1918, granting women over 30 who were married or had property the right to vote.

But why is this significant, and what does Manchester have to do with it? The limited terms of the act may already appear restrictive – but it was a long hard fight up until this point, and the people of Manchester played a massive part.

The act was after all revolutionary in itself. Up until this point, very few women could vote in elections. Now 8 million could. It was a defining piece of political – and public – history, also giving servicemen over the age of 19 and other men over 21 the right to vote.

It was not only Manchester which was the birthplace of the Suffragette Movement – the organisation which fought for greater female representation – but Manchester’s radical past put issues of wider political rights into the national spotlight.

Without the strength and determination of a number of political movements and statements originating from Manchester and the North West, it could be argued that the contents of The Representation of the People Act would have been much later and perhaps even more limited.

Manchester is after all a place which has fought long-term against repression and for greater representation. It is often referred as an ‘industrial city’, but out of this also came intelligence and articulacy – people meeting to discuss social conditions and the possibility of greater fairness.

The boom and bust of industrialisation (and the limiting Corn Laws of 1815) which negatively affected the working classes led to Manchester’s radical stance even in the early 19th century – with a group called the Blanketeers leading a march from Manchester to London in 1817 to petition for parliamentary reform. No wonder Northerners are known for being loud, then.

For what these people of Manchester were marching against were extremely limiting political and economic conditions. The whole of Lancashire only had two MPs at this time, and only men who owned freehold land with a value of 40 shillings or more could vote.

To make matters worse, these votes could only be cast in Lancaster. And trains weren’t an option then. Not even the Megabus.

Manchester continued to make a stand. By 1819 the scale of the city’s political radicalism was evident – as a crowd of more than 60,000 people gathered at St Peter’s Fields (where Peter Street is now) on 16 August to call for a repeal of the Corn Laws and greater representation.

Speaking at the gathering was Henry Hunt, an orator who held the view that not only should more men be allowed to vote, but single tax-paying women too.

Tragically, what followed the speech was what has since become known as The Peterloo Massacre – as cavalry panicked and charged into the crowd, killing at least 15 people and injuring hundreds.

But what events of Peterloo contributed to on behalf of the political radicals was a wider push for parliamentary representation, reform and fairness. This outcry in Manchester led to the passing of the Six Acts, the founding of The Manchester Guardian and the path towards the 1832 Great Reform Act.

Around this time The Chartist Movement also began, with a considerable force in Manchester and a continued push for parliamentary reform – with apparently some members in favour of greater female suffrage too.

For Manchester was certainly radical in more ways than one. It made a stand not only in its fight for reform, but for women’s rights too – especially the right to vote.

When you think of women’s voting rights, you may think of the Suffragettes – and you aren’t wrong. But organised attempts to fight for female political rights started even earlier in Manchester, with The Manchester Society for Women’s Suffrage founded in 1867. Member and secretary Lydia Becker even took the step of writing to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli at the time.

By the 1870s, organisation in Manchester had made such mark that a movement for greater women’s representation reached a national scale. At this point, the people involved were known as Suffragists, not Suffragettes, prioritising reform by peaceful methods – as expressed by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies founded in 1897 by Millicent Fawcett.

Then in 1903 came the Sufragettes. Straight outta Ardwick. Well, nearly.

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Sylvia and Christabel, using their home on Nelson Street (just off Oxford Road, now the location of The Pankhurst Centre you can still visit today) as their base.

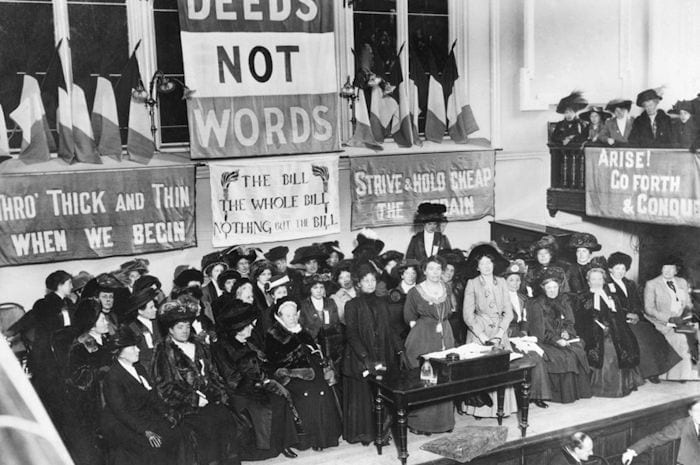

The work of the WSPU in Manchester became known as The Suffragette Movement and gained national recognition, especially because of the often radical and visible methods used by its members to fight for greater female representation.

There were mass marches through Manchester and London, speeches, and even a protest at the Free Trade Hall in 1905 where they challenged Winston Churchill on the subject of women’s suffrage. Christabel Pankhurst was jailed for her involvement in this.

But these radical acts in Manchester created a resonance in the wider country and helped guide public opinion towards widening electoral representation, and in 1918 The Representation of the People Act marked a milestone not only in women’s voting rights but in Manchester’s role as a radical city.

It was not until 1928 that full voting rights for men and women were granted, but 1918 was a key foundation with Manchester playing a historic role. Millions of working class men gained the right to vote too.

The history of fighting for fairness and promoting change has continued here. Forward-thinking women including novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, birth control advocate Marie Stopes and co-founder of the RSPB Emily Williamson have all been based in the area.

Manchester is also home to one of the first LGBT Foundations, celebrated its first openly gay mayor, and even has plans in place to found the UKs first LGBT retirement home.

And history continues to be made, with radical women including Manchester University’s first female vice chancellor Dame Nancy Rothwell, Real Junk Food Project founder Corin Bell, poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy, actor Julie Hesmondhalgh, Maxine Peake and many more all working here.

The city is celebrating too. A stunning new piece of street art called Serenity has been unveiled in Manchester’s Northern Quarter, set to be part of The Cities of Hope street art convention.

In the shadow of Stevenson Square, where the Suffragettes once gathered defiant over 100 years ago, Serenity is the first of the street art convention’s Tributes to Hope.

And hope continues in the work of people throughout the city today. You can still visit The People’s History Museum which showcases and celebrates political change in the city through time, The Working Class Movement Library, and The Pankhurst Centre itself.

Manchester is a place that cares what it represents and who it represents. A place to be proud of.

- This article was last updated 7 years ago.

- It was first published on 6 February 2018 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Chorlton Library gets a stunning renovation unveiling hidden treasures

How one selfless act sparked a career dedicated to saving lives

Former sheltered housing transformed into safe haven for vulnerable youth

Manchester and Los Angeles prove that opposites really do attract