Why Manchester has an Abraham Lincoln statue and square

- Written by I Love MCR

- Last updated 2 years ago

- City of Manchester, Cornerstone, History

It might seem a bit odd at first thought for Manchester to have a statue of Abraham Lincoln, as there are no obvious links to the popular president of the United States. But according to the archives at Manchester Central Library, our city was a very important ally to Abe Lincoln’s Union during the American Civil War.

The statue of the American president is located just off Albert Square, in the smaller, easily missed, Lincoln Square.

Its location is not really befitting for one of the most iconic figures in American history; the square is terminally quiet and surrounded by dull office blocks.

The statue, which was sculpted by George Grey Bernard after the First World War, is a reminder of the historic link between the US Civil War and Victorian Manchester.

Beneath the bronzed sculpture is inscribed a letter to the people of Manchester, commending them for a historic act of solidarity against the slave trade.

As the largest processor of cotton in the world, Manchester took a strong moral and political stance by supporting Lincoln despite his blockade of the Confederate states beginning in April 1861. This measure drastically reduced supplies of cotton reaching Liverpool and, therefore, the cotton mills of Lancashire.

The aim, for Lincoln, was to out-manoeuvre the Confederate states, win the civil war and ultimately abolish the US slave trade.

But Manchester and the surrounding area, which had once clothed the world, found 60% of its mills falling idle, largely as a result of the blockade.

Read more: Greater Manchester’s most notable statues and sculptures – what they stand for and where to find them

Mill and shipping companies lobbied for the blockades to be destroyed, and in cities as nearby as Liverpool, opposition to the embargo and support for the Confederacy mounted.

But in a meeting at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in 1862, in a show of defiance despite potential starvation and destitution, workers agreed to maintain support for Lincoln and the embargo.

The meeting took place just as the cotton famine was beginning to have serious distress across the county. US aid ships followed the letter to the shores of the north west, offering relief to starving mill workers in a gesture of gratitude.

It is remarkable that the workingmen’s address offered support to the Northern cause. This was a time when it was widely thought that the quickest way to restore the cotton supply, and hence end the depression, was for Great Britain to recognise and intervene on behalf of the Confederacy.

In supporting Lincoln and the Union, Manchester working people selflessly put their principles ahead of their economic self-interest.

Lincoln wrote a letter on 19 January 1863 to thank the people of Manchester for their support. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives holds a photocopy of the transcript received by Abel Heywood, the Lord Mayor of Manchester and the Chairman of the Chairman of the meeting of Workingmen, on 9 February 1863.

In January 1865, months before Lincoln’s assassination, US Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment. Slavery throughout the United States was officially abolished.

Soon after, as the US constitution was being rewritten, the Confederate states which had been crippled by the embargo were being eliminated by Union forces.

By the time the South surrendered, Manchester’s derelict mills were being swept ready for the city to begin the daunting process of re-igniting its once glorious industrial flame.

But Manchester’s roots in the fight against human rights abuses, and slavery in particular, predates even Lincoln’s birth.

In 1787, leading British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson gave a speech at what is now Manchester Cathedral.

After being met with hostility in Liverpool, Clarkson was given a much warmer welcome in Manchester and the city positioned itself at the vanguard of the anti-slavery movement here in the UK.

A set of documents relating to Lincoln held by Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives (including the rest of Lincoln’s letter) can be found here.

- This article was last updated 2 years ago.

- It was first published on 10 June 2020 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Iconic Northern Quarter menswear store makes a comeback with new styles and big ambitions

The charity celebrating ten years of making music accessible for all

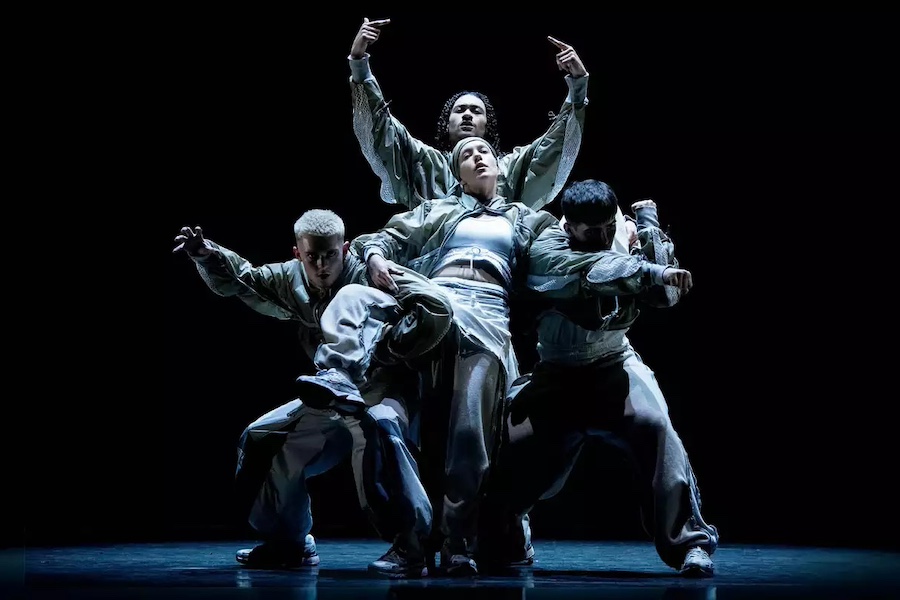

Review: The House Party at HOME is ‘a bold exploration of modern class divides’

Ukrainian artist studying in Manchester shares inspiring message about living life to the full

How The Salutation became a cornerstone of Manchester’s story