The secret Cold War history of Manchester’s underground tunnel network

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 1 year ago

- Community, Cornerstone, Featured, History

Beneath the bustling heart of Manchester lies a clandestine world, a silent witness to the tension-filled era of the Cold War – the Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange (GUTE).

A labyrinth of reinforced concrete tunnels, this ageing relic, shrouded in secrecy during its mid-1950s construction, continues to operate silently, serving as a crucial infrastructural space facilitating modern communications.

But it wasn’t always that way.

The Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange

Information about GUTE remains elusive, buried deep within the city’s foundations.

This subterranean marvel, conceived amid international turmoil, serves as a testament to Manchester’s preparedness during the Cold War.

Yet, the reality of its shape and scale is obscured by the very nature of its underground existence.

Manchester’s Atomic Bomb Shelter

Initially designed as a ‘hardened’ bunker to safeguard vital national communication links from atomic bomb attacks, GUTE’s construction began in the early 1950s.

However, even before its completion in 1958, advancements in nuclear weaponry rendered its original purpose obsolete.

Despite formal declassification in 1968, the aura of secrecy surrounding GUTE persists, giving rise to myths and speculations.

Join us as we explore the echoes of a time when the city’s vital communication hub was poised to weather the storm of global tensions, hidden deep beneath the bustling streets of Manchester.

The History of the Guardian Telephone Exchange

This unassuming structure conceals a fascinating history tied to the Cold War era.

Post-World War II, with nuclear tensions escalating between the United States and the Soviet Union, the British government envisioned worst-case scenarios.

In response, a groundbreaking decision was made to construct a new city-centre telephone exchange, hidden deep underground.

The Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange, completed in 1954, extended 115 feet beneath Manchester’s streets, boasting a complex network of tunnels, rooms, and amenities.

Although never deployed for its intended nuclear command purpose, the Guardian Exchange remained classified under a ‘D Notice’ until 1968.

Even in the 1970s, individuals with knowledge were bound by the Official Secrets Act.

Today, remnants of the Cold War marvel persist beneath Manchester, repurposed for British Telecom cables.

Why was it built?

Similar installations were constructed in London (Kingsway) and Birmingham (Anchor). Kingsway, built under conditions of secrecy, extended existing World War II shelters, while Anchor Exchange was located in Birmingham’s city centre.

GUTE, funded by NATO, accommodated around 35 engineering maintenance staff, smaller than its counterparts in Kingsway and Anchor.

Funding for these extensive tunnels was deemed vital for strategic defence infrastructure.

Plans for similar facilities in Bristol and Glasgow were considered but never materialised.

The rationale behind constructing these underground facilities was based on the importance of telecommunications post-nuclear attack.

The cables ran underground, and connections were reinforced by at least two separate routes, safeguarded by protected repeater stations. Main exchanges and terminals were fortified to ensure the resilience of the communication network, emphasising their role as the “ganglia of the thermonuclear bomb-resistant brain.”

The strategic placement and protection of these facilities were crucial, ensuring the continuity of organised government functioning even in the aftermath of a nuclear strike. It’s a scary thought.

Challenges and Controversies

In 2004, a fire disrupted 130,000 telephone lines, highlighting the ongoing significance of this hidden relic.

The Guardian reported at the time: “The blaze hit a 1,500-metre tunnel carrying cables between Manchester and Salford.

“Built in the 1950s to connect a long-abandoned bomb-proof underground telephone exchange to the wider network, it was being refurbished. An electrical fault is thought to have caused the fire rather than arson, as its source is almost impossible to reach.

“Firefighters were alerted to the blaze below Chapel Street at 3.20 am, near Manchester town hall, and were busy through the day making the tunnel safe for BT engineers to go down and assess the damage to the cables.”

A subsequent break-in in 2005 triggered a terror alert, too.

Construction and Layout

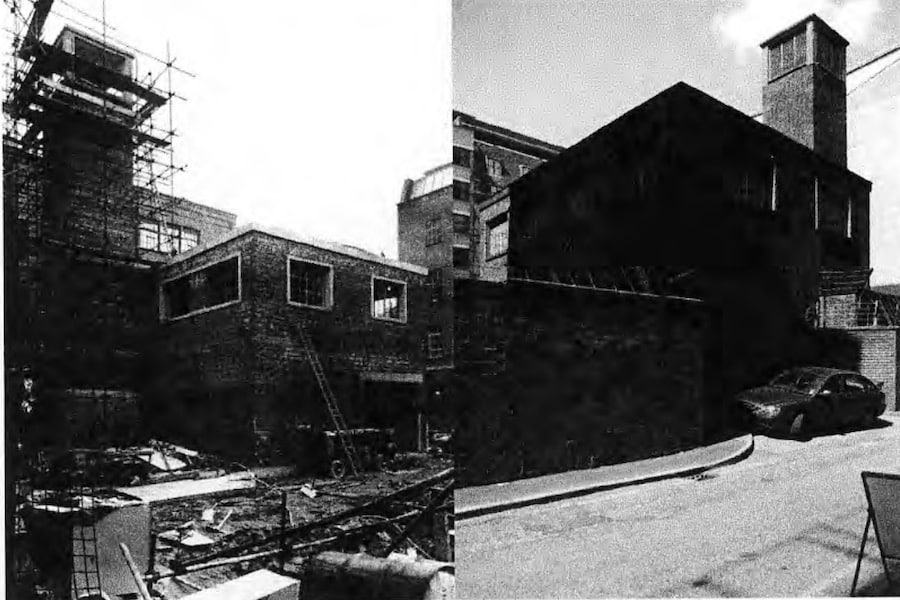

Built between 1954 and 1957, Guardian Exchange, along with counterparts in Birmingham and London, aimed to provide secure communication during nuclear threats.

With a depth of 115 feet and tunnels of approximately 2 meters in diameter, it cost around £4 million. Construction began amidst secrecy during land clearance for the Piccadilly Plaza complex.

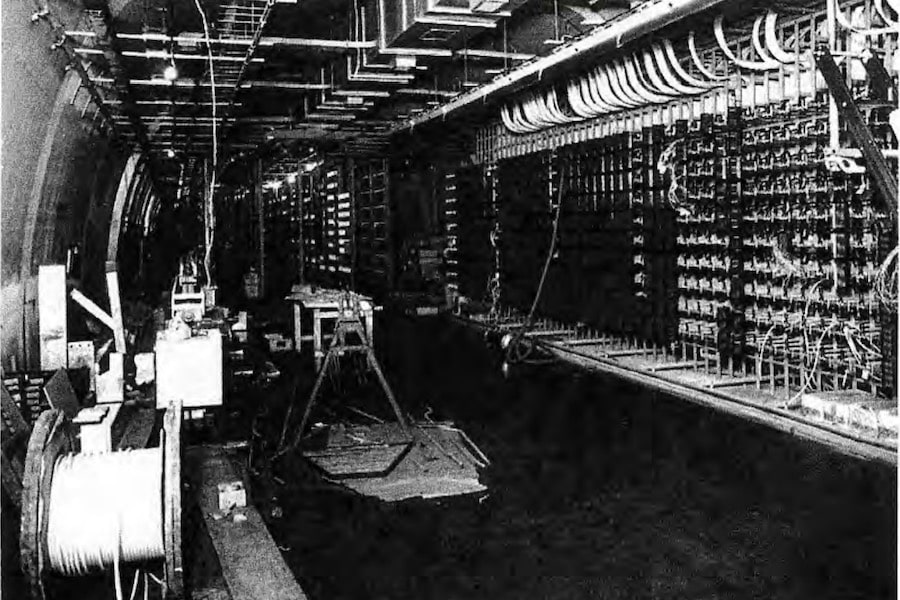

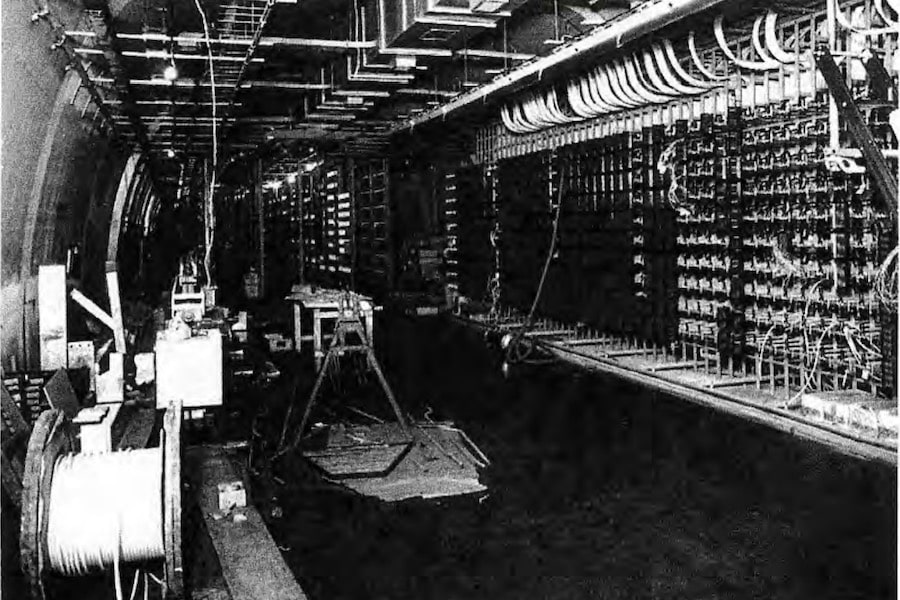

The best description of the tunnel network under Manchester is from 1974, published in a construction journal at the time. It reads: “The existing network, established in 1956, spans the cities of Manchester and Salford.

Cable tunnels originate from Ardwick on the south side, pass beneath Deansgate, continue northward under the River Irwell, and extend westward across Salford.

These tunnels interconnect with a grid of large-diameter tunnels beneath Piccadilly, housing the telecommunications apparatus, along with its associated plant and support systems.

“The tunnel structures are predominantly horseshoe-shaped but exhibit significant variations in size and detail. To convey the scope of the accommodation, there are eight primary types of tunnel cross-sections, each featuring two, three, or four subdivisions.

“The interiors are lined with plain concrete, ranging from 10 to 36 inches in nominal thickness. Notably, the ventilation tunnels, constructed in 7-foot-diameter cast iron bolted rings, run beneath the apparatus tunnels.

“The entire tunnel system is situated at depths between 100 and 200 feet, entirely within Bunter sandstone, known for its high moisture content. Cable entry shafts, featuring 12-foot-diameter bolted cast iron lining, are strategically located on derelict plots near the existing telephone exchanges of the cities. From each shaft, a short spur extends, constituting a tunnel with a nominal diameter of 9 feet 6 inches.”

Multi-functional Complex

The Guardian Exchange housed not only a Trunk Telephone Exchange but also generators, sleeping quarters, Piano, a kitchen, and even a well-furnished bar.

Despite equipment removal, the main tunnels still echo the Cold War era. If you’re looking for signs of it today, the site is only accessible via deep shafts, the only publicly visible evidence of the tunnel’s existence.

The two main entrances in the city centre are located at 56 George Street and within an office building on (New) York Street, 42 known as York House.

You can check out this creepy exploration of the tunnels under Manchester below.

Despite the absence of the looming threat of nuclear confrontation, discussions about a possible ‘nuclear bunker’ beneath Manchester have stirred public interest for decades.

Even after the formal declassification in 1968, speculations and myths persist, fueled in part by the mysterious disappearance of web-based resources and increased security measures around known access points.

Attempts to unveil the secrets of GUTE have faced obstacles.

Formal inquiries to BT and the facilities management company went unanswered, adding to the air of secrecy. The last known public visit occurred in 1997, leaving a trail of mystery with a group from the Manchester Civic Society describing their descent into the depths as ‘entering somewhere in Piccadilly.’

Potential uses for the tunnel?

Prior to his retirement in 1983, Roy Howard, then Planning Controller for BT, set about vigorously finding a new use for GUTE, to no avail.

He had considered that it may have had some value in advancing the Picc-Vic heavy rail tunnel project but could not convince the Passenger Transport Executive (PTE) of such.

You can read more about that forgotten dream here

The Greater Manchester Police were also approached to see if they had any ‘Special Branch purposes’ that would suit the site, and the Greater Manchester Council (GMC) were averse to the associations with anything ‘nuclear’ as they were ‘Working for a Nuclear Free City‘ at the time.

Contrary to common belief, the tunnels persist as a crucial piece of urban infrastructure, playing a vital role in sustaining the functionality of the information-age city.

Operating as a pre-existing, secure environment, these underground passages serve as an ideal space for the installation of fibre-optic cables,

As the Guardian Exchange remains hidden beneath the city’s surface, its historical significance and potential vulnerabilities add layers to Manchester’s history, reminding us of the enduring echoes from a time when the world lived under the looming shadow of Cold War tensions.

- This article was last updated 1 year ago.

- It was first published on 8 January 2024 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Failsworth’s funniest export wants your laughs (and some new parquet flooring)

Meet the Salford creators changing the face of digital storytelling

Tradition gets a makeover in WAKE – the electrifying Irish show coming to Factory International

Irresistible tapas spots in Manchester that’ll make you feel like you’re in Spain