The Real Doc Martin of Salford shares his rollercoaster ride as a GP

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 1 year ago

- Books, Featured, Tameside

Martin Stagg, from Salford, was a GP for over thirty years in Ashton, as patients from all streams of life settled across from him and began with one familiar line: ‘I don’t know where to start, Doc.’

He’s penned a new book, The Real Doc Martin: The Humour, Sadness and Absurdity of a Life in General Practice, showcasing his hilarious, sad and absurd experience in working as a GP in Greater Manchester.

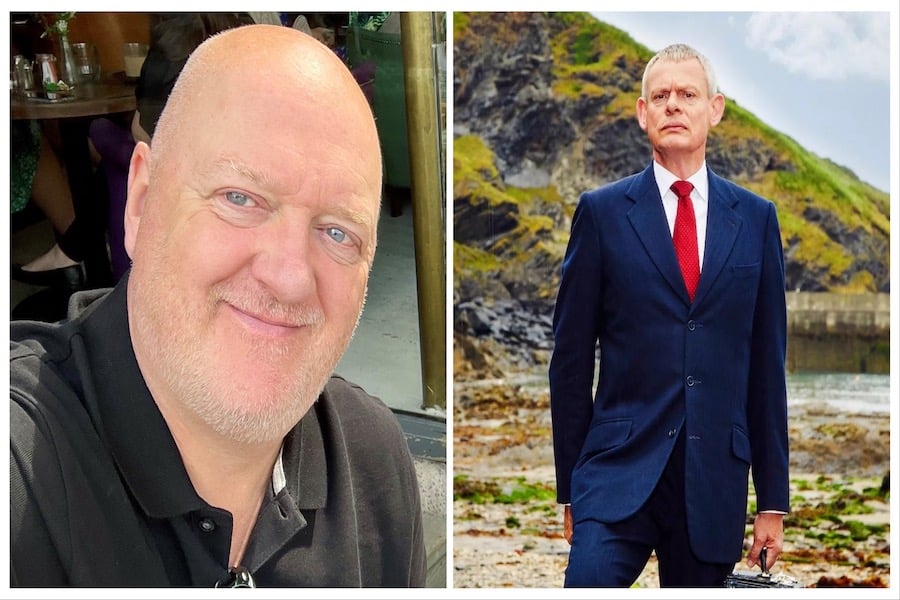

The Real Doc Martin takes us on the journey of the daily ups and downs of a real GP, in a setting less picturesque, but certainly no less amusing, than the fictional TV doctor’s seaside town.

He takes us on a wild ride through the humour, sadness, and frequent absurdities of a career at the grassroots of medical care in the UK, as well as the traverses and changes to our beloved NHS over the years.

The memoir delves into the memorable cases which marked Martin’s career, from the patient attempting to alleviate her pet allergies by spraying her inhaler at her unsuspecting cats, to the retired GP he succeeded, who, in the spirit of a bygone era, shared a dram of whisky with each of his patients during rounds.

So we sat down with Martin Stagg, the Real Doc Martin, to talk about his career and new book.

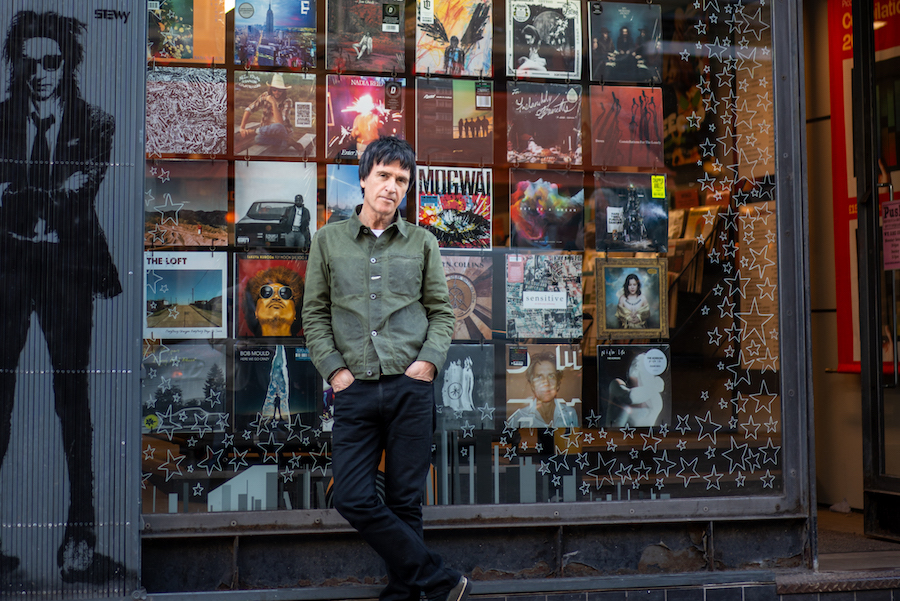

Martin Stagg, The Real Doc Martin

What inspired you to write The Real Doc Martin and what message or experience do you hope readers will take away from it?

It really started as a collection of funny anecdotes that I had accumulated during my time working as a GP.

Friends and colleagues would often suggest ‘writing a book’, and I decided to follow their advice.

After writing down a few of these stories I realised that some of the more serious tales were perhaps even more interesting, so started to include these, alongside stories from medical school and my hospital training posts.

I suppose the biggest message in the book is that real patients are every bit as varied, funny and chaotic as their fictional counterparts on TV. Mr Towell was a case in point.

A man with severe lung disease, he managed to cause a small explosion whist smoking a cigarette through a gap in his oxygen mask.

A less dramatic encounter, but one that had a big emotional impact on me, was with a patient called Ben, who continued to spray his wife’s perfume in their bedroom long after she had passed, immersing himself in the memory of her presence.

Can you share a particularly memorable patient case that stands out to you from your years as a GP, and how it impacted you personally or professionally?

I remember being quite affected by a home visit that I did as part of a project while I was still a medical student. It was to a single mum who lived in a fairly grim, high-rise flat. She had two small children who both had Down’s Syndrome, and associated heart problems.

The lift was not working on the day that I visited, and the flat was humid, partly due to the large amount of bedding and clothes scattered around that she was attempting to dry.

Both of the children had already had some cardiac surgery and were waiting for more procedures.

Their lives were tough. Really tough. It helped me to appreciate just how lucky I am. Most of us are really, certainly most of the time.

You mention the humorous and absurd aspects of life in general practice. Could you recount one of the funniest or most absurd moments you encountered during your career?

A patient attended with a printout from an internet search engine, wondering whether they had that condition.

The article was about prostate cancer.

I informed the patient that they did not have this disease.

The patient was irritated that I was so certain, despite not having performed any examinations or investigations. I was so confident that I was right for a few reasons; firstly, because they were only 23 and, secondly, because the patient was female (with no history of gender dysphoria).

Unfortunately, nothing in the article had pointed out that either of those facts would have cancelled out her unnecessary worries.

Your memoir touches on the changes within the NHS over the years. Could you elaborate on some of the significant shifts you’ve observed and how they’ve affected the practice of medicine?

I think, nowadays, that we all have higher expectations of both our health and of healthcare provision if we actually develop an illness.

These expectations are a good thing in themselves but do have an impact on the provision of care.

Feeding our expectations, of course, are the many tremendous improvements in diagnosis, treatments, and prevention.

Earlier diagnosis is aided by the increased availability and precision of digital scanning technologies.

There are far better immunotherapy treatments now, particularly effective in treating some childhood cancers.

The use of vaccinations have now expanded to HPV vaccination, which is aimed at the prevention of cervical cancer, potentially wiping the disease out entirely in the UK within this current lifetime.

In your opinion, do you believe there was a ‘golden age of the NHS, or have societal expectations simply evolved? How do you think this impacts the doctor-patient relationship?

As above, I think that expectations have changed in response to the improvements in investigations and treatments over time.

There is an inevitable negative effect on the doctor- patient relationship, as people are understandably anxious or upset at any delays.

They realise that such delays can allow illnesses to become more serious or dangerous to them.

For example, there is much more widespread availability of joint replacement surgery now.

The waiting lists for such procedures now were obviously not there before the procedures themselves were invented, and then expected.

I don’t believe that there was ever really a “golden age” as such, although nostalgia can colour memories that way. This cosy view of the past is fed by many of the feel-good series

that we enjoy about the recent past; shows such as “Call the Midwife”.

In balance, though, it was much easier to get a GP appointment as demand was genuinely less in the past, and patients visited their GPs much less often 40 years ago.

I think that most people’s ideal of a future golden age of the NHS would include rapid access to their chosen GP, shorter waiting times in A and E and minimal waiting times for hospital appointments and referrals. All of these could theoretically be helped by increased funding and staffing levels, with the obvious affordability implications, of course, being the downside.

Your experiences range from practising medicine in Manchester to spending a summer in Botswana. How did these diverse settings shape your approach to healthcare, and what did you learn from each environment?

People are people, wherever you are and have more in common than that which separates them.

I think that you should be able to learn from any environment, as long as you remain open to this.

The most impressive doctors who I have worked with have all been open to new learning. They have accepted that they don’t know everything and that the understanding of medical science continues to evolve.

I have spent the majority of my life in the Manchester area, so take it for granted as the norm, I suppose.

I attended Manchester Medical School and did my hospital training across many of the area’s teaching hospitals. My GP training was in Saddleworth, but the rest of my career was then spent working in a practice in Ashton-under-Lyne.

I was only in Botswana for 3 months but was very grateful for the opportunity to experience a completely different country and healthcare system, even for that short period. Healthcare provision in Botswana in the 1980s was far behind that of the UK but was actually relatively good compared to many other African countries, in part due to a good and uncorrupt government, which tried to give equitable funding across the country.

The population density was very low outside of the capital city, Gaborone, which had the only large hospital in the country. Most citizens, therefore, had a long way to travel to access any level at all of hospital care in the small handful of other hospitals.

Patients travelled for days, often on foot, to be seen at our hospital walk-in clinics.

Realistically, their expectations from their actual health, and from their health service, were far lower than we have in the UK.

I think my exposure to the country and its stoical people has helped to give me some ongoing sense of perspective.

An example of the stoicism and different expectations was the very limited range of painkillers on offer to women in labour. The midwives were very reluctant to proceed beyond paracetamol, and felt that my references to stronger drugs being used in the UK demonstrated the softness of Europeans generally.

One of the most special memories that I have of my time there was being a visiting medic at an outlying community clinic. This meant driving on dirt roads along the edge of the Kalahari Desert for a few hours, and then treating all the patients who had been brought to the clinic on the day. On a few occasions I went on my own; exciting but also a bit frightening at the same time, especially when a sandstorm struck on my first trip.

Have you enjoyed your career in Greater Manchester?

Absolutely. It is a great area to live and work in. I was lucky enough to spend the majority of my career in an excellent practice, with dedicated and hard-working GP partners, and trainees, all sharing the workload as fairly as we could.

We had a great management and admin team; brilliant and hard-working nurses, nurse practitioners and clinic room practitioners. The reception staff too, were skilled and hardworking, often in a seemingly thankless task, trying to balance the genuine needs of patients against the availability of resources.

I have great faith in the staff in our district hospitals as well as in the Manchester teaching hospitals. I trained in many of them, and visited relatives in others, as well as receiving treatment in some myself.

What do you love most about Manchester?

Mancunians of course – in the broadest sense; I’m from Salford and worked in Ashton for most of my career. Mancunians tend to have a natural, dry sense of humour, which helps to puncture any pomposity, and break the ice.

Manchester City centre is now so much more lively than when I grew up, maybe in part due to the Commonwealth Games bounce that enhanced the city’s self-confidence and growth.

It is now chock-full of excellent restaurants and bars, as well as great theatres and music venues, especially the Apollo. I was lucky enough to see the Buzzcocks and Joy Division play on the same bill live in Manchester, and old enough that Joy Division were actually the support act!

I also love the fact that Manchester centre has all of this stuff but is still small enough to get across easily.

What do you hope readers, especially those considering or already in the field of medicine, will gain from The Real Doc Martin in terms of insights or lessons about the realities of being a GP in today’s healthcare landscape?

Perhaps some sense of perspective. Things have changed so much over my 40-plus years of work and training, but most changes were barely noticed at the time they were

introduced.

Some of the most significant changes have been in preventative medicine, successfully treating things like high blood pressure and cholesterol, thus helping to significantly reduce the numbers of victims of both heart attacks and strokes. A great success story.

Many more things have improved than have deteriorated, and newspaper articles are not always the best way of seeing how well the NHS still does most of the time.

In terms of being a GP, the working hours have greatly reduced over the past forty years, but the stress levels remain very high, as GPs feel squeezed by the pressure of many of the treatment delays in the rest of the NHS. They also feel weighed down by the continually increasing demand for more and more appointments and the understandable frustration that patients feel when they cannot always see the GP of their choice as quickly as they would

like.

The Real Doc Martin: The Humour, Sadness and Absurdity of a Life in General Practice by Martin Stagg is published on 22 February 2024, priced £10.99.

You can pick up a copy by clicking here

- This article was last updated 1 year ago.

- It was first published on 23 February 2024 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

The Manc aerobics queen who trained the Corrie cast is helping raise charity cash

Ancoats to get even cooler as independent market set for MOT garage site

“Manchester is not Britain’s second city, it’s the first” – Jeremy Clarkson