Pick of the plaques: five extraordinary people who made their mark in Manchester

- Written by Yvonne Goldsmith-Rybka

- Last updated 8 years ago

- Community, Culture

You’ve probably noticed the blue plaques scattered round Manchester on or close to buildings where people who have shaped the rich history of the city lived, worked or were active. Here are five of our favourites.

Elizabeth Raffald, Marks & Spencer, Exchange Square

Entrepreneur doesn’t even begin to describe this extraordinary woman and her work, who became famous for her cookbook ‘The Experienced English Housekeeper’ published in 1769. The book was reprinted 13 times, and deemed so good even Queen Victoria would copy sections into her diary. Eat your heart out, Jamie Oliver.

Whilst her husband sold flowers from a market stall, she opened up a confectionery shop which doubled as a cookery school and outside catering business. Forget Deliveroo, Raffald was known for her personal service, providing catering across the city including the Exchange Coffee House. She was the first cook to offer the traditional combination of fruit cake, royal icing and almond paste, better known as ‘wedding cake.’

As well as having nine children, Elizabeth ran a host of pubs, a post office, the first Salford newspaper, a stagecoach company creating links to London, and a domestic service agency. She also published the first Manchester trade directory. Elizabeth Raffald achieved all of this in her relatively short lifetime of 48 years. What a woman.

Elizabeth Raffald’s plaque is actually black as it’s a replacement of the original which was destroyed in the IRA bombing of 1996. It’s close to the site of The Bull’s Head Pub which she operated and from where she ran her coaching service.

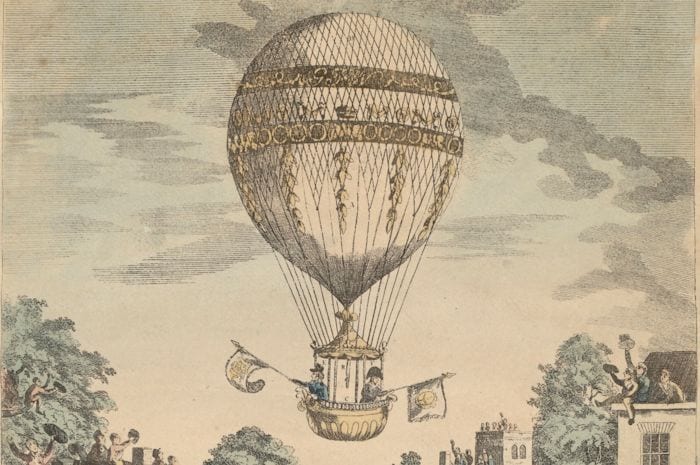

James Sadler, Balloon Street

James Sadler worked as a pastry chef in his family business, The Lemon Hall Refreshment House in Oxford but made his name as a balloonist in 1784 when he became the first Englishman to fly.

He became an overnight celebrity, as balloon fever gripped the nation. Whole towns would close down for the day to watch the balloonist in action, often accompanied by his cat. He was adored, to the extent that 20-30,000 people would regularly turn up whenever he announced a balloon flight. They even helped him fund his expensive ‘hobby’ as Sadler would display his balloons in public and charge for the privilege.

He survived fifty flights over forty years. But, devastated by the death of his youngest son Windham Sadler in a ballooning accident, he devoted the rest of his career to science, helping improve cannon design, as well as inventing the table steam engine, despite having no formal education.

On 12 May 1785 he made his third ascent from a field in Balloon Street, Manchester, eventually landing in Radcliffe. In 2015, a public square in Manchester, Sadler’s Yard, was named after him, close to which his blue plaque can be found.

Robert Owen, Royal Exchange Building

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, Wales in 1771 but made his fortune in the cotton trade in Manchester. He first worked as a draper’s assistant at Satterfield’s Drapery in St Ann’s Square and borrowed money to invest in spinning mules, a new development in the cotton industry at the time.

At the age of 21 he became manager of Bank Top Mill, a new, steam-powered mill with 500 employees, where he gained a perspective on the harsh conditions facing factory workers and spent the next ten years trying to improve them, putting forward his ideas of reform at the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society and Manchester Board of Health. He subsequently became managing partner at Chorlton Mills and in 1799 moved to New Lanark, Scotland, to manage the extensive cotton mills which the partnership had purchased, where he put his ideas into practice.

His reforms included paying higher wages for shorter hours than his competitors, a programme of childcare, and workers education. A prolific writer and campaigner, he became one of the most influential thinkers and social reformers of his time, and is regarded as the founder of the Co-operative Movement. His blue plaque can be found on the side of the Royal Exchange Building, close to where he first worked, and his statue outside the Co-operative Bank.

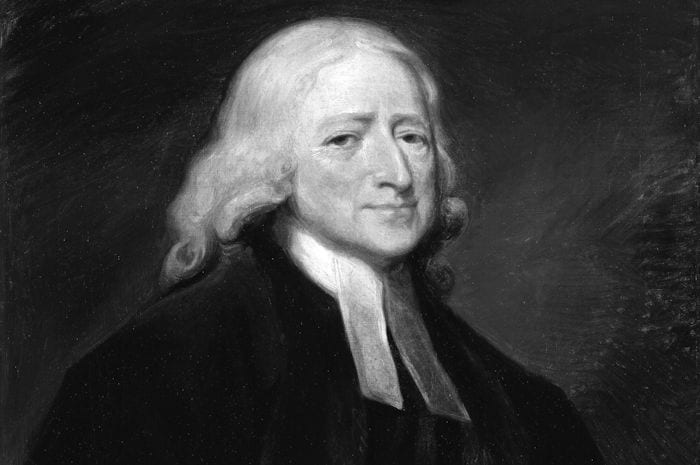

John Wesley, Central Hall, Oldham Street

John Wesley was an Anglican cleric who is credited as founder of the Methodist Church. Travelling across Great Britain and Ireland on horseback, he is said to have given two to three sermons each day.

A courageous man who, despite being barely 5’ 6” tall, regularly placed himself in situations of extreme physical danger when anti-Methodist riots were rife, he continued to preach and proseltyse.

He wrote his own journals providing invaluable records of a country undergoing social and economic change. He was widely respected and campaigned on many social issues of the day, including prison reform and the abolition of slavery, with his mission introducing a number of homes and hostels for working men, a women’s refuge, and maternity care. A preacher of abstinence, he was vegetarian and teetotal, warning against the dangers of alcohol abuse. Effigies of Wesley were displayed in pubs dunked in ale in protest.

He opened the second Methodist Preaching House in Manchester in 1781 in Central Hall on Oldham Street. It was bombed during the war but a new hall was rebuilt on the same site, where his plaque can be found. He was listed no. 50 in the BBC’s list of 100 Great Britons.

Doris Speed, Sibson Street, Chorlton

Doris Speed played Annie Walker, landlady of The Rovers Return, in Coronation Street from 1960 to 1983. She didn’t exactly have a normal childhood, touring with her musical parents, making her stage debut aged 4. She was hooked and followed in their footsteps to follow a life on the stage. Tony Warren wrote the role of Annie Walker specifically for her after seeing her perform the role of Judith Bliss in Noel Coward’s Hay Fever.

Her time playing Annie Walker will always be remembered as the show’s golden age. When her on-screen husband, Jack, played by Arthur Leslie, died, she contemplated leaving. But ever the performer, she was quoted as saying ‘Arthur always said the show must go on…and so it will.’

She stayed another thirteen years, until in 1983 the Daily Mirror published a story revealing the fact Doris was not 69, but 84. She died in 1994, aged 95, smoking a cigarette and reading a copy of the novel To Sir With Love.

Unlike her conservative, tight-lipped character, she was a lifelong socialist and was awarded an MBE in 1977 for services to television. She never married and lived with her mother for the 23 years she appeared in the soap, in the house on Sibson Street, Chorlton, where her plaque can be found.

- This article was last updated 8 years ago.

- It was first published on 14 December 2016 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Head down the rabbit hole for Adventures in Wonderland with Z-arts

Major rail investment set to transform Manchester-Leeds commutes

“His presence will be deeply missed” Children’s hospice bids farewell to their visionary CEO

Has Gordon Ramsay created Manchester’s ultimate bottomless brunch?

The Clink celebrates ten years of empowerment and second chances