The Northern Soul scene is bigger than ever – 46 years after the first Wigan Casino all-nighter

- Written by Terry Christian

- Last updated 3 years ago

- Culture, Music, Videos, Wigan

It’s almost 46 years since Russ Winstanley booked Wigan Casino for its first Northern Soul all-nighter. On Sunday 23rd September 1973, the faithful paid 75p each to dance to rare black American records from 2am until 8am.

And although the price has gone up a bit since then, the scene is now bigger than ever. It has been the subject of two British films in the last ten years and a huge catalogue of CD compilations occupying the racks of even your local supermarket.

It was Wigan Casino that partially influenced Robert Stigwood to make the film Saturday Night Fever, and household names from Peter Stringfellow to Mick Hucknall were inspired by the Northern Soul scene.

When ITV showed a documentary on the Casino for its This England strand in 1977, it was seen by an audience of 27 million – and the reverberations are still being felt. In fact, in 1978, this tumbledown ballroom was voted number one disco night club in the world by US Billboard magazine ahead of New York’s famous Studio 54.

TV adverts featuring Nothern Soul songs Al Wilson’s The Snake, Frank Wilson’s Do I Love You and Rubin’s You’ve Been Away have plugged everything from cars to KFC and cat food. There’s instant street credibility to be had for any artist or brand associated with a scene that has always been wild, free and grass-roots.

The phrase Northern Soul was coined in June 1970 by the late London journalist and rhythm & blues guru Dave Godin in his weekly Blues & Soul magazine column to describe a danceable type of rare soul cherished in clubs across the north and Midlands.

The sound was based on the 4/4 beat of the Four Tops’ Tamla Motown classic I Can’t Help Myself, although it would come to be associated with faster stompers as heard during the Wigan Casino era from 1973 to 1981. But the most important element was its emotional, soulful content.

The momentum of the scene in the Sixties derived from the British white working class, which instinctively saw common causes that linked it to the black American experience.

But in Britain, the marker wasn’t race but class. Godin once said that it’s not the colour of your skin that counts against you so much as the way you talk or your educational disadvantages or what your daddy does for a living.

The greatest aspect of Northern Soul is its resolute determination to call its own shots. Although plenty have tried, it has never been owned by an elite. Godin reinforced this by adopting the signs and slogans of America’s black civil rights movement: the clenched fist and Keep the Faith badges.

He even kept it safe from the Hush Puppies-wearing cultural élite in London by including the word ‘northern’ in the name. The headline of that particular column was That Soul Sound with the Up North Groove and his reference was the club where it truly began – the legendary Twisted Wheel in Manchester.

The scene is now bigger than ever – albeit more scattered – with dedicated Northern Soul conventions in Los Angeles, Hamburg, Gothenberg, Las Vegas, New York, Detroit, Chicago and Tokyo.

The records, always expensive and collectable, now fetch a king’s ransom, especially on the Japanese market, with original vinyl prices going through the roof.

In 1996, Scottish double glazing businessman and soul collector Kenny Burrell bought Frank Wilson’s Do I Love You for a reported £15,000. A demo of Darrell Banks’s Open the Doors to Your Heart went for a mere £900.

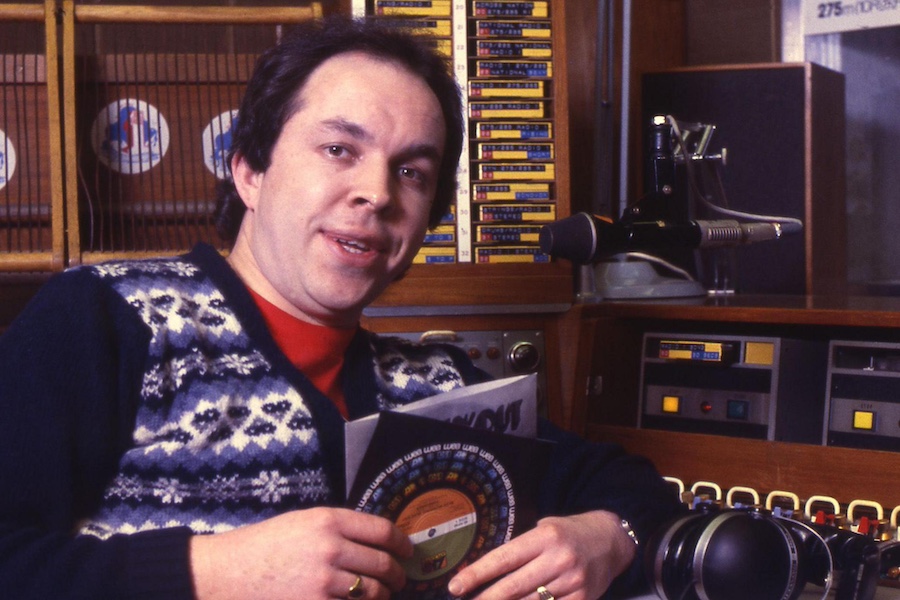

This popularity is reflected on the internet, with sites dedicated to its infamous clubs – the Twisted Wheel, the Golden Torch, the Blackpool Mecca – and its DJs, especially Richard Searling, the big taste maker on the Northern soul scene, who has long-running-soul shows on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Stoke and Solar Radio and should really be on BBC Radio 2. His fabulous book Wigan Casino, Setting The Record Straight 1973-1981 came out last autumn.

There are online juke boxes, recommended lists of records and footage of performances at Wigan Casino all over YouTube. The compilation CDs and the internet are opening up the scene to those who for years have had their noses pressed against the glass looking in.

The greatest achievement is that a whole generation of soul fans from the Sixties and Seventies has saved, catalogued and cherished a raft of independent black American culture that otherwise would have been lost and is now making it available to the next wave of enthusiasts.

Terry Christian’s top five Northern Soul tunes

Darrell Banks: Open the Door to Your Heart

(1966 USA Revilot, UK Stateside and Black London promo)

Darrell Banks was tragically shot dead in the street a couple of years after this was released. The flip side Our Love is In The Pocket is another big favourite.

Sandi Sheldon: You’re Gonna Make Me Love You

(1966 Okeh records)

Produced by Van McCoy. Legend says it reached the Twisted Wheel via the Wolverhampton DJ Froggie Taylor who bought it from a dealer who got it in a bag of records he bought from John Peel.

Eddie Parker: Love You Baby

(1968 Ashford)

Tracked down in the Eighties working on a car production line in Detroit, Eddie Parker has God-like status for his two monster records I’m Gone and this ten-ton truck of freneticism and vocal power.

Frank Wilson: Do I Love You?

(1965 Soul S3519)

A run of 500 of these was pressed as Tamla Motown promos in 1965. Only two are known on the scene – the rest were destroyed. A true northern treasure.

Gerri Grainger: I Go to Pieces (Everytime)

(1972 USA Eric, UK Casino Classics (BMG))

Makes my eyes brim with tears every time I hear it. A sentimental whirlwind: pass the Kleenex, a tear is painting my cheek.

- This article was last updated 3 years ago.

- It was first published on 22 September 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Head down the rabbit hole for Adventures in Wonderland with Z-arts

Major rail investment set to transform Manchester-Leeds commutes

“His presence will be deeply missed” Children’s hospice bids farewell to their visionary CEO

Has Gordon Ramsay created Manchester’s ultimate bottomless brunch?

The Clink celebrates ten years of empowerment and second chances