Letter written by first suffragette to be jailed is discovered in Canada

- Written by Emily Oldfield

- Last updated 7 years ago

- History, Oldham

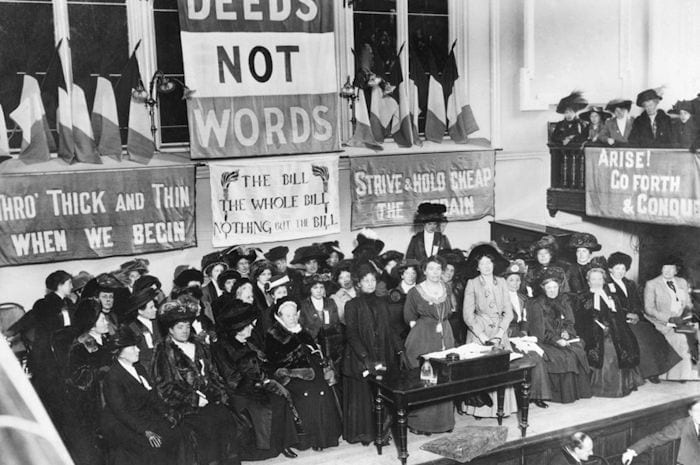

A previously unseen letter from the first suffragette to be imprisoned for her part in campaigning for women’s voting rights has been found.

The letter appears to have been written by Annie Kenney the day after she was released from Strangeways Prison in 1905.

The sister to whom it is addressed later emigrated to Canada, where the letter was recently discovered by Oxford historian Lyndsey Jenkins.

The letter – sent from the former suffragette headquarters of the Pankhurst House on Nelson Street in Manchester – provides a unique perspective on what it was like to be the first woman sent to prison for protesting for the vote.

When Annie Kenney and the suffragettes were active in the early twentieth century, protesting women were often seen as a threat.

She was imprisoned for her part in a protest during a Liberal rally at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester in October 1905. During the meeting, which was attended by Winston Churchill, Annie and Christabel Pankhurst interrupted it with a cry: “Will the Liberal government give votes to women?”

Whilst Christabel was taken into custody, Annie was jailed for three days.

Her jail sentence is seen by many as a key movement in women’s fight for the vote, leading the suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union to fight for the vote in more direct, radical ways. For example, it was following this that the Votes for Women placards were launched – a slogan which is still recognized today.

Annie Kenney played a key role in the suffragettes’ campaign, going on to found the first London branch of the WSPU in 1906 with Minnie Baldock, even though she came from a northern working class background.

Born in Springhead in Saddleworth in 1897, the fourth of twelve children, Annie worked in local cotton mills from the age of 10. She endured these conditions for over 15 years, experiencing the difficulties first-hand – with working days up to 12 hours long and even having one of her fingers ripped off by a bobbin.

It was this first-hand experience of the hard work of women in society which probably influenced Annie’s involvement in the suffragette movement. She became involved in 1905 after seeing Christabel Pankhurst speak at a club in Oldham.

The letter contains the line: ‘I am able to send money home every week’, suggesting that the family still may have been in a difficult financial situation.

Annie would later become part of the senior level of the WSPU herself, not only co-founding the London branch, but becoming deputy in 1912 and arranging meetings with leading politicians like David Lloyd George and Sir Edward Grey.

Kenney was jailed a total of 13 times during the course of her lifetime because of her protest activities and attracted crowds of thousands wherever she spoke, including ‘2,000 supporters’ she describes at a Manchester protest meeting.

The letter will be displayed at Gallery Oldham from 29th September, on loan from the British Columbia Archives.

- This article was last updated 7 years ago.

- It was first published on 21 September 2018 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Manchester and Los Angeles prove that opposites really do attract