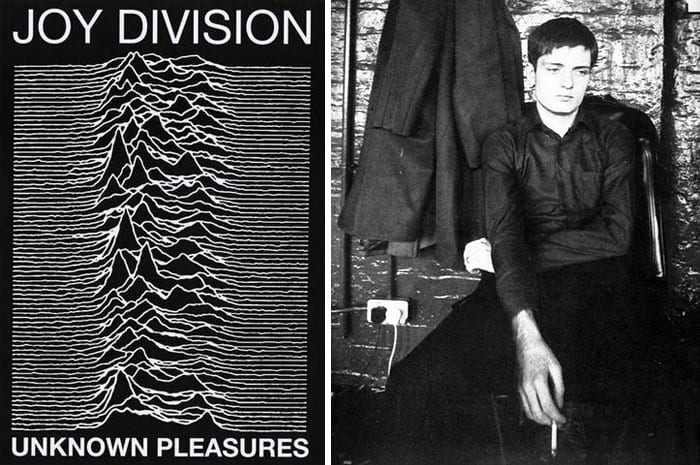

Joy Division’s ‘Unknown Pleasures’ – forty years on

- Written by Terry Christian

- Last updated 6 years ago

- Culture, Music

It’s terrifying for those of us of a certain age to think that this weekend (15th June) is the 40th anniversary of the release of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures.

It’s been all over radio and press the past few days, yet it’s worth remembering that as far as most of us Manchester gig goers were concerned, Joy Division were interesting but not as big as Buzzcocks or Magazine. Perhaps they equalled The Fall.

It’s also worth noting that their Martin Hannett-produced album recorded at 10cc’s state of the art 24 track Strawberry Studios wasn’t even the biggest album produced there that year. That would be the third album by another Manchester band also managed by 10cc’s then manager Harvey Lisberg – Sad Cafe.

Having had a modicum of success, Sad Cafe used 10cc’s Eric Stewart to produce their album Facades at Strawberry, an album which peaked at number 8 in the UK album charts.

An indicator of how big Sad Cafe were that year was that when Buzzcocks played the Manchester Apollo in the late autumn with Joy Division supporting, they just about managed to fill it, whilst Sad Cafe sold out three consecutive nights for their hometown gigs.

Although Unknown Pleasures garnered great reviews it took a while for it to filter through a crowded market. 1979 was unusual in that the singles and album charts were of a decent quality.

In fact, the week that Unknown Pleasures came out it was the summer of great funky floor fillers like Anita Ward’s Ring My Bell, Earth Wind & Fire’s Boogie Wonderland, Sister Sledge’s We Are Family, McFadden & Whitehead’s Ain’t No Stopping Us Now, Edwin Starr’s H.A.P.P.Y as well as singles by David Bowie, The Clash, Squeeze, Blondie, Elvis Costello, The Ruts, Janet Kay, Roxy Music, and The Skids.

In fact, apart from footballer Kevin Keegan releasing a single and The Dooleys and Dollar, it was a pretty tat-free musical summer in the charts.

I spent that summer working at Butlin’s in Bognor Regis with a mate of mine, mopping floors in the kitchen, drinking pints of snakebite and trying to avoid fights with the various scousers, Glaswegians and Geordies who seemed to have migrated south in search of work.

It was when I returned to polytechnic in London that I first got assailed by Joy Division and Fall fanatics who made me feel that Manchester was uber cool. That made a change from being treated as if I’d parachuted in from some Coronation Street theme park.

It helped that I’d been an old school mate at primary and secondary school of Buzzcocks drummer John Maher and a classmate for 5 years at St Bede’s of Chris Nagle, Martin Hannett’s sound engineer at Strawberry Studios.

Proxy stardom had a certain sex appeal in those days, believe me, and mixed with my (ahem) unreconstructed Mancunian world view, I suppose it was because these bands were firm favourites with John Peel and the music press at the time that it was a game shifter for me. It made me feel validated and I made a point of trying to make myself like both Joy Division and The Fall at the time.

This wasn’t unusual in my youth. After all, this was still really the age of prog rock. I’d already suffered forcing myself to listen to Yes, Peter Gabriel’s Genesis and Pink Floyd and Emerson Lake and Palmer albums until I was vomiting out of my ears and finally saying “Yes I get it, I surrender, it’s great and sophisticated”.

Joy Division were hard to work out. They weren’t David Bowie, they weren’t Buzzcocks, they certainly seemed influenced by Magazine and that serious post-punk sound, but they demanded a lot from the audience.

I remember seeing them support Buzzcocks at the Apollo and that uncomfortable feeling of liking them, but at the same time thinking they sounded a bit too rocky. Yet the singer was so ‘new wave’, I mean live, they could have been a prog rock band.

They had a breathtaking power and loud guitar sound that was all squashed down on their records by Hannett, but for anyone thinking they were punk they sounded suspiciously like the sort of progressive rock with long songs and clever lyrics that punk was supposed to have blown away.

I remember when I was back at polytechnic in London straight after seeing that gig and these women I knew who were all south east London and Kent girls were all buzzed about me seeing Joy Division. The pressure was on for me to say I’d preferred them to Buzzcocks on the night. But the truth was they were still a tough listen for a young lad.

Now here we are 40 years on and an album that, although selling well in dribs and drabs, never charted is still being hailed as of historic significance.

For Manchester it was the start of an independent northern scene. A band who’d turned down a major label to stay in Manchester and reinvest in Manchester and created a confidence and vibe all of its own and, more importantly, helped a young Mancunian lad socialise with Londoners of the opposite sex and get a first sense of pride, outside of football, in his home city through the eyes of others.

- This article was last updated 6 years ago.

- It was first published on 14 June 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Iconic Northern Quarter menswear store makes a comeback with new styles and big ambitions

The charity celebrating ten years of making music accessible for all

Review: The House Party at HOME is ‘a bold exploration of modern class divides’

Ukrainian artist studying in Manchester shares inspiring message about living life to the full

How The Salutation became a cornerstone of Manchester’s story