Cereal Killer Café? Crowdfunding: Democratising the Business World or Funding Folly?

- Written by Simon Binns

- Last updated 9 years ago

- Food & Drink

I ask the question based on two examples of the public paying for start-ups this week, both in the food sector.

“Crowdfunding has

certainly moved on.”

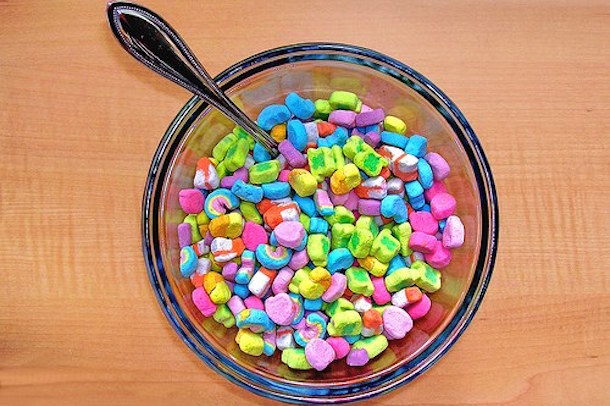

Down in London – Shoreditch, to be precise, which is increasingly becoming an irony free zone – two young brothers have managed to convince the London public that they should dig deep into their pockets and find enough loose change to help raise the £60,000 they need to open a café that only sells cereal.

You heard.

Cereal Killer Café is the ‘UK’s first cereal café’ – probably with good reason. Cynics may suggest it is also likely to be the UK’s last cereal-only café, but whatever your view, they still managed to raise tens of thousands of pounds without having to rely on a bank loan or Mum and Dad’s remortgage.

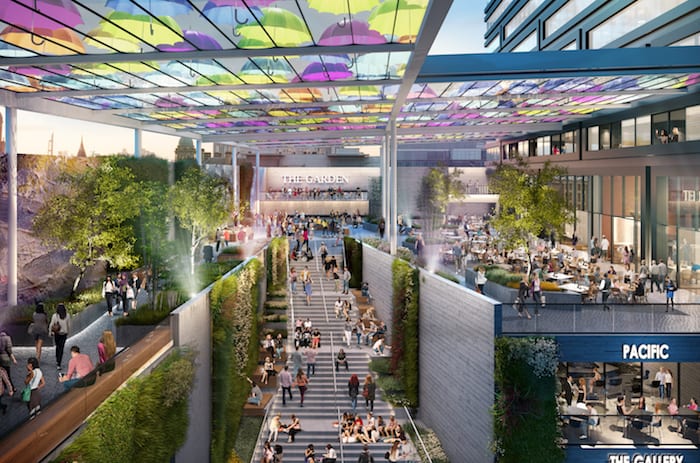

Closer to home, the team behind excellent Hoole brasserie Sticky Walnut announced that they’d hit their £100,000 target to open a new venture, Burnt Truffle, closer to Manchester.

Gary Usher and his extremely talented mob have so far raised £101,725 from a total of 855 backers, largely harnessing the power of Twitter (they are well worth a follow, as Usher tends to, erm, speak freely).

Crowdfunding has certainly moved on. I once tried to crowd-fund a car on Twitter as I was sick of getting the bus. I managed to raise £32, and a tenner of that was from one person.

All of this, or course, relies on goodwill. And while it has democratised the business world in some ways, you have to wonder if this kind of funding is supporting long-term businesses or indulging half-ideas and fads that exist in a fairly short moment.

Certainly, you’d be hard-pressed to find a crowdfunding page that has a business plan on it, or sales forecasts, or supply chain scenarios. People are selling a concept, without many of the nuts and bolts that will actually hold it together. Or not.

I suppose it’s down to the business to make itself viable after the initial leg-up. Especially the likes of the cereal café.

But in a venture like Burnt Truffle, crowdfunding could have played a major part in a genuinely exciting and high-quality restaurant which will have a positive impact on the reputation of the city.

Another element of funding businesses this way is that as well as generating cash, those start-ups are also generating customers – and loyalty to something that doesn’t even exist yet.

It’s a sense of ownership without having to give over an actual shareholding. And as long as investors are happy with those terms, the relationship works.

When coffee company Grindsmith launched an appeal for £10,000 last December, it tiered the levels of investment, from £5 to £1,000, offering incentives at each level, from a free slice of cake to your name on the wall.

As the more traditional routes to investment start to find their feet again, would be punters have picked up the slack when it comes to helping new food and drink operators realise their dream.

It’s not a solution for all. More than half of all Kickstarter appeals fail.

But for those who can deliver on their promise, it can work. Which is why it has become such a hit in the food and drink sector.

Me? I had to buy my own car.

- This article was last updated 9 years ago.

- It was first published on 4 November 2014 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Didsbury Sports Ground needs your help to rise again after devastating floods

Do you know someone who could be the next star of Matilda The Musical?