The story of Manchester in 101 objects: #13 the Jacobite Rebellion in Manchester

- Written by Ed Glinert

- Last updated 6 years ago

- Culture, History

Story: The Jacobite Rebellion in Manchester

Object: Bonnie Prince Charlie’s “bed”

Year: 1745

Location: Chetham’s Library

In an age when the question of who has the rightful claim to the throne is non-existent, it seems incredible how much energy, violence and time was spent in pre-industrial times on the subject.

Although the monarch was supremely powerful in those days, paradoxically there were no clear rules over the succession – hence successive wars and battles, notably the Wars of the Roses.

The last year it was an issue in England was 1745. But the drama goes back to the 1680s when James II (James VII in Scotland) became more and more attached to Rome and was encouraged to quit by the Protestant establishment. He voluntarily gave up the throne on 23rd December 1688.

How did his heirs feel about that? Both his daughters, Mary and Anne, became ruling queens – but then they were Protestants, while his son, James Francis Edward Stuart, who was only six months old when his father quit, did not.

Soon the Catholic claimants were barred by law – the Act of Succession of 1707. So when Queen Anne, James’s daughter, died in 1714, those who would be king who did not willingly accept this discrimination launched a succession of rebellions – Jacobite rebellions (Jacobus being the Latin for James) – to put the Catholic Stuarts back on the throne.

The main rebellion was in 1745 and became known as The ’45. The most glamorous heir to the throne at that time was not James II’s son, James Francis Stuart, but his son, Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Young Pretender (a false re-working of the French word “pretendant” – claimant).

On 28 December 1745, Bonnie Prince Charlie and his troops arrived in Manchester from Scotland and paraded outside St Ann’s Church, chosen because it was Protestant. Locals had been expecting their arrival for weeks.

As news of Charles’s imminent arrival spread around Manchester, Peter Mainwaring, a JP and monarchist, ordered the town bellman to visit the homes of leading locals loyal to King George, urging them to arm themselves with guns, swords and shovels to beat off the Jacobites.

Nevertheless, a crowd spurred on by the promise of £5 each and a cockade they could wear in their hats in return for their support, cheered on the Jacobites who, in turn, celebrated as if they had “captured” the town.

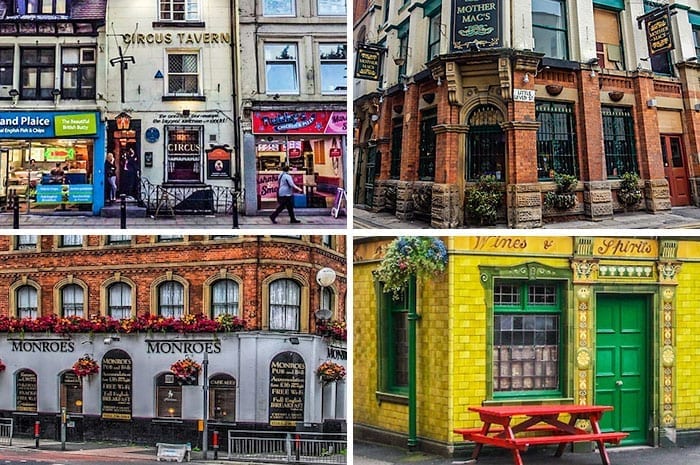

The Jacobite soldiers billeted themselves at the pubs in the market square, such as the Bull’s Head (where New Cathedral Street lies). The prince stayed with a Mr Dickenson on Market Street (where Urban Outfitters is now).

John Byrom, a leading figure in Manchester at that time, who is believed to have secretly supported the Jacobite cause, wrote a notable epigram about the events:

God bless the King! I mean our faith’s defender

God Bless – no harm in blessing – the Pretender!

But who pretender is, or who is King,

God bless us all, that’s quite another thing.

The Prince’s army gathered considerable support in Manchester. Their aim was to march to London, adding more and more supporters as they travelled.

But in one of the greatest tactical blunders in English history, the Jacobites turned back at Derby early in December, even though London was in a state of panic about their possible arrival.

A battle to decide finally who should be in charge of Britain – the Georgians or the Stuarts – took place at Culloden near Inverness in April 1746. The Jacobites lost and have never launched a fresh attack on the throne.

On display in Chetham’s library is an elaborate oak bookcase which in 2014 was discovered to have been made out of an early 16th century bed that belonged to Lancashire gentleman Adam de Hulton. It was slept in by the Pretender at de Hulton’s home near Bolton on his way to Manchester.

Read how Manchester got its name here. For more information on Ed Glinert’s tours of Manchester, click here.

- This article was last updated 6 years ago.

- It was first published on 15 March 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

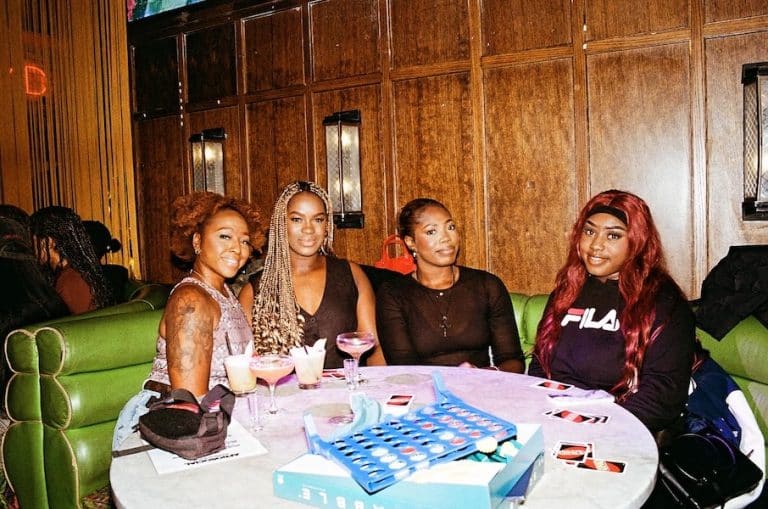

Afrosocial is changing the game for Afro-Caribbean professionals in Manchester

From paws to applause: Could your dog be Manchester’s next big opera star?