Strangeways: over 35 years since Britain’s toughest prison riot

- Written by I Love MCR

- Last updated 2 months ago

- Cornerstone, History

Strangeways Prison in Manchester was an unnatural world of 900 male prisoners and 140 male officers. An existence without money, women or liberty.

Now often referred to as ‘that big cock’ in the cityscape, Strangeways in Cheetham Hill was Britain’s largest jail. A dark star hidden behind vast Victorian walls in the heart of Manchester. Back then, it was the only ‘hotel’ in Manchester that was always 100% full and eventually became the location of Britain’s most notorious and violent prison riot.

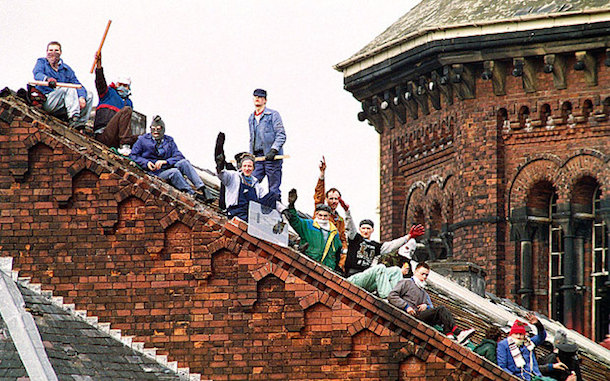

35 years ago, 1,500 prisoners broke out of their cells and took over the prison. Local (and subsequently national) media caught almost every moment of the rooftop siege, but what made Strangeways remarkable was that the cameras had already captured the brutal conditions that existed inside the prison. A stark warning of what was to come.

When this hidden world finally erupted, two men died, and hundreds were injured.

Strangeways was struggling to cope with the rising tide of prisoners coming through the gates. Built for 900 men, Strangeways now housed 1,500. Undoubtedly, the pressures and tensions of imprisonment increase when two or three men share a small living space. A cell designed in the Victorian age for one man. Even sharing the same toilet facilities- typically a plastic bucket. A human warehouse. A Victorian building still standing in the 90s in which people were treated as if it were still Victorian times

To add to the tension and built-up toxicity, prisoners were allowed just one hour of exercise per day. For the other 23 hours, they were locked up in their cells. Tension, anger, frustration; all increasing the threat of insurrection. .

Into this powder keg stepped an idealistic young governor, Brendan O’Friel, who had a reputation as a moderniser. A man who cared about the welfare of the prisoners. He spotted a culture amongst some prison officers that had no place in his prison. There was a staff club next door to the prison, which served alcohol. As a result, some officers were returning to work after their lunch under the influence, affecting their judgment and aggravating prisoners.

Some officers wore gollywog badges from jam jars as symbols of their prejudice against black prisoners. O’Friel put a stop to this practice and introduced female officers to the wings. The presence of women led to fewer fights.

Strangeways was bursting at the seams. Two prisoners in particular (one alpha male, both unhinged) wanted to make a point – that they’d had enough of the medieval rules.

The conspiracy started in the prison chapel, an understaffed space in which 300 prisoners could gather together. It was a recipe for disaster that erupted onto the rooftops. The prisoners did everything they could to show that they were at the end of their tether.

Pushing coping stones off the roof, throwing slates at officers, and even attacking prisoners with certain criminal offences. During the siege of the rooftops, the prisoners made themselves comfortable, blasting music (‘I’ve Got The Power’ by Snap was a popular choice) and cooking steak butties until 400 riot-trained officers were briefed to take back control of the prison and its roof. After three weeks, many younger, scared prisoners surrendered, and others got cold and bored. After one of the ringleaders was captured, the rooftops were set on fire.

Copycat riots broke out in other prisons up and down the country.

The most aggressive prisoners had a further ten years added to their sentences as a result of the siege.

As a result of the riot, the Woolf Report led to changes in the prison system. Sloping out ended. A prison ombudsman now hears prisoner complaints.

- This article was last updated 2 months ago.

- It was first published on 2 April 2015 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

£14.5m cultural and creative hub to ‘mark a new chapter’ for Stockport Town Centre

Now you can own a piece of TV history and support a much loved NHS Charity

The welcoming Manchester community where board games build friendships

Best bars and pubs to watch the football and live sport in Manchester

Discotheque Royale vs Piccadilly 21s: which was your favourite 90s Manchester club?