Review: The Lemon Table is powerful, gripping and beautifully performed

- Written by Glenn Meads

- Last updated 3 years ago

- Theatre

As many of us get used to getting back to seeing live productions face-to-face and online, here is a play which celebrates exactly that from the perspective of a spectator and a performer.

Madonna’s lyrics from the hit song Music rings true when watching this beautifully performed solo piece. “Music makes the people come together.”

And HOME understand that some audience members are not ready to come together, so they have socially distanced performances, too.

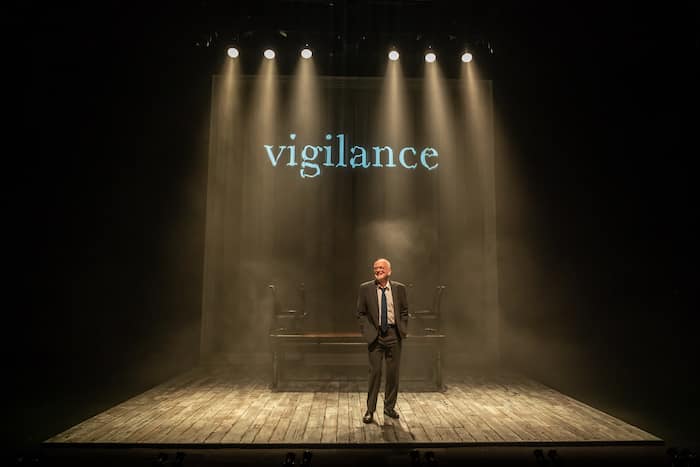

Olivier award winning actor Ian McDiarmid (known for everything from Shakespeare to Star Wars, he played Palpatine in the Sci Fi saga) plays two characters who each bring something different to the piece.

In Vigilance, we meet an audience member who lives for live music.

But where this piece really resonates is the fact that he explores his annoyance with fellow audience members who flick through programmes in the middle of a performance or cough non-stop, and he also shares his disdain for the ‘munch bunch’ who rustle sweet wrappers during moving moments.

This is particularly resonant for many audience members who were keen to return following the pandemic, but who had maybe forgotten about the people in the seats next to them, having spent so much time at home.

Likewise, these noisy individuals forget that there is anyone else is around them.

Beneath this layer lies something far darker and unsaid.

This spectator uses classical concerts as a great escape, as there is an impenetrable silence between him and his partner of 20 years.

Frankie Bradshaw’s vast set, complete with a huge picture frame highlights this emptiness and explains why the spectator is so fixated on the behaviour of others.

The Silence enables McDiarmid to convey the fact that he is a chameleon, he steps inside the mind of a character and has an amazing ability to contort his body and face to become a music composer nearing the end of his life.

In terms of performance, this is an absolute masterclass, and he plays a man addicted. Addicted to music and alcohol, his creative juices are running as dry as the bottle he drinks from.

Following the acidic and biting dialogue in the first half, this story is slower paced and therefore not quite as satisfying.

These two stories, adapted from Julian Barnes’ 2004 collection The Lemon Table, might be more effective the other way round with the musician speaking first, followed by the spectator.

Directors Michael Grandage and Titus Halder manage to keep the audience on their toes, gripped to the proceedings for a combination of reasons.

Paule Constable’s lighting design mean that the set becomes something far bigger than it seems to the eye.

The Lemon Table pulls back the red curtain to reveal the inner self of a performer and an audience member.

McDiarmid has never been better and when he takes his bow at the end, as himself, you realise the power and majesty that you have just witnessed – and why it’s good to be back enjoying live theatre at HOME.

The Lemon Table is at HOME until 20th November. Tickets are available here.

- This article was last updated 3 years ago.

- It was first published on 18 November 2021 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Strictly high-flying: Kelvin Fletcher trades dance moves for dirt jumps at Arenacross

Worker Bee: Meet Peter Hook, legendary New Order and Joy Division bassist

Hilton Manchester Deansgate’s superstar chefs shine on the world stage

How Sounds from the Other City became the UK’s most unforgettable independent festival

Piehard: where to get the best pies in and around Manchester