Remembering Manchester pioneers Alcock and Brown 100 years after first non-stop transatlantic flight

- Written by Ray King

- Last updated 6 years ago

- City of Manchester, History

One hundred years ago this weekend, a specially modified First World War Vickers Vimy bomber, an assemblage of wood, canvas and wire, dipped its nose into an Irish bog near Connemara in County Galway.

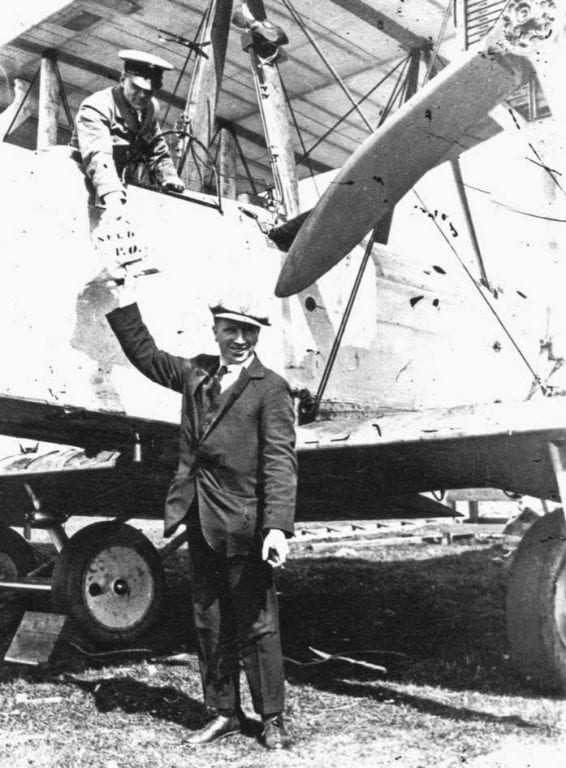

With two pioneering Manchester aviators at the crude controls in the open cockpit, the aircraft had flown almost 2,000 miles – the longest single flight ever at the time, which earned a unique place in history as the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.

Coming a mere 15 years after the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright recorded the first ever powered flight, Alcock and Brown’s heroic achievement was nothing short of astonishing.

The Vickers Vimy, powered by two Rolls-Royce engines – developed after that legendary meeting at Manchester’s Midland Hotel in 1904 – had taken off from St John’s in Newfoundland, Canada.

The pilots, despite their electrically heated clothing (which didn’t work), fur gloves and fur-lined helmets, endured bitter cold, a snowstorm and dense fog, the failure of their radio, and deafening noise from a broken exhaust pipe during their epoch-making 16 hours and 28 minute flight.

The flimsy plane often skimmed the Atlantic’s waves, rising to no more than 12,000 feet, and at times flew blind through banks of fog. Neither pilot was injured when the plane crash landed at 8.40am on 15th June 1919, and they were able to claim the £10,000 prize offered by the Daily Mail in 1913. Competition had been suspended for the duration of the war.

John “Jack” Alcock was born in Seymour Grove, Firswood, Manchester in 1892 and gained his pilot’s licence 20 years later, becoming a regular entrant into aviation competitions. He became a military pilot at the outbreak of war and was taken prisoner in Turkey after his bomber was forced to land through engine failure.

While a prisoner of war, Alcock resolved to attempt the Atlantic crossing.

Arthur Whitten Brown was born in Glasgow in 1886 to American parents who soon afterwards moved to Manchester. An engineer by trade, he was a military flyer in the war and he too was taken prisoner after being shot down over Germany. Afterwards he concentrated on developing his expertise in aerial navigation.

At the end of the war, Alcock approached Vickers with a view to piloting the Atlantic attempt. Soon afterwards, Brown, then unemployed sought a post with the plane makers. His long distance navigational skills made him the ideal candidate to accompany Alcock.

The pair were treated as heroes after their flight and both men were knighted within days by King George V. Alcock and Brown flew to Manchester on 17th July 1919 and were given a civic reception by the Lord Mayor.

But tragedy was to strike within months.

Sir John Alcock was killed on 18th December 1919, aged just 27, when his Vickers Viking crashed in fog near Rouen en route to the first post-war Paris air show. His grave in Manchester’s Southern Cemetery is marked by an elaborate memorial.

Sir Arthur Brown died in 1948 and is buried in Buckinghamshire.

Such was their achievement that three memorials were raised in Newfoundland near the flight’s starting point and two mark the landing place in County Galway.

The monument to Alcock and Brown hung for many years above the concourse of Terminal 1 at Manchester Airport is now cited in the atrium by the airport’s railway station. A spokesman for the airport said they were working on ideas to mark the centenary of the conquest of the North Atlantic.

Their Vickers Vimy aircraft was rebuilt and is now on display in the Science Museum in South Kensington, London.

A century after their historic and gruelling flight (legend has it that Brown crawled along the wings to de-ice the engines) transatlantic flight is routine.

There are literally dozens of flights a week from Manchester to major cities in the United States including Virgin Atlantic’s routes to Atlanta, Orlando, Los Angeles and New York; American Airlines’ flights to Philadelphia; United’s to Newark, and Thomas Cook routes to New York and Las Vegas.

There are also flights from Manchester to Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, Chicago, Houston and Miami.

Pioneers Alcock and Brown really started something. And the story of their momentous flight is retold in a new illustrated book Yesterday We Were in America (The History Press, £18.99).

The book’s Irish author, Brendan Lynch, said: “The people of Manchester should be out in the street celebrating this anniversary. These were amazing people – two very brave men.

“I am considering a book launch in Manchester and I’m going to make it my business to get in touch with the people in France where Sir John Alcock was killed to see is some kind of memorial can be raised there to mark his death.”

He added: “Over time, when I think about what they did I shiver. They were very brave men but also so capable. Brown was a first class navigator and Alcock was a most reliable man.

“They made the perfect pair.”

- This article was last updated 6 years ago.

- It was first published on 14 June 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Fast, fierce and unmissable: Manchester Thunder are bringing Netball like you’ve never seen it before!

Review: Girl on the Train at LOWRY is a’ tour de force in psychological drama’

Where the Michelin Guide recommends to eat in Manchester