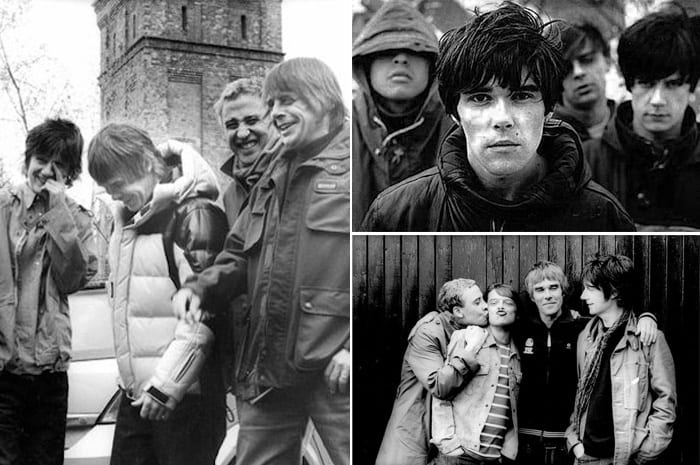

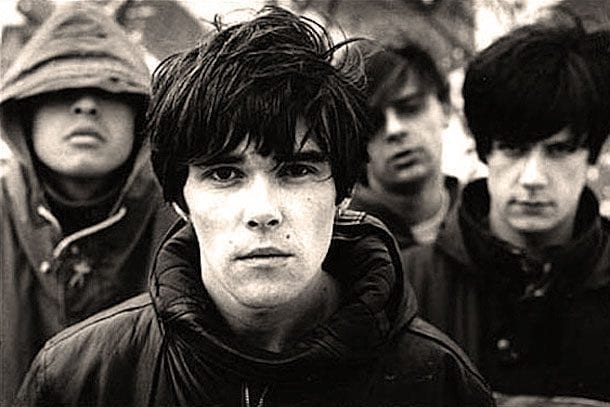

Happy 30th birthday to the Stone Roses album that changed things forever

- Written by Terry Christian

- Last updated 6 years ago

- Culture, Music

May 2nd 2019 is the 30th anniversary of The Stone Roses’ debut album.

On the day it came out, I was interviewing and recording a session for my Key 103 show with The Pixies. They’d just been doing the rounds of the record shops that Monday morning in Manchester to press the flesh and see how the sales of their top ten album Doolittle were faring.

“Who are this band The Stone Roses?” Frank Black and Kim Deal asked me.

It seemed that in every record shop in Manchester all the kids were buying The Stone Roses debut album.

It was released the same week as The Cure’s Disintegration and Simple Minds’ The Street Fighting Years and outsold them both put together by three to one in Manchester.

Not bad for a band who were almost scorned out of existence and crept along as outsiders for the best part of four years before anyone took any real notice.

In many ways, The Stone Roses were the ultimate Manchester band and exuded the cool of a peoples’ band. An “everybody hates us and we don’t care” attitude that the overnight success of The Smiths, the Tony Wilson-groomed Joy Division and uber-hipness of Buzzcocks never had to suffer.

Nobody helped The Stone Roses and they barely helped themselves. But they were the band every Mancunian had been waiting for. And front man Ian Brown was a genuine rock star.

Manchester is a city with a certain moral looseness. Loyalty to your own has always been a legacy of its immigrant past. A city with no old money. You’re admired for excelling at what you do rather than what your parents did.

Manchester bands had ruled the singles charts in the 1960s. In 1965, Herman’s Hermits outsold the Beatles and Freddie and The Dreamers, Wayne Fontana and The Mindbenders and Herman’s Hermits topped the USA Billboard charts for six consecutive weeks. Those particular bands were placed at numbers 1,2 and 3 in the US Billboard charts in the last week of April 1965. Then came the Hollies.

In the late 70’s, punk rock sowed its seeds on fertile and radical ground. Manchester virtually invented independent music with labels like New Hormones, Rabid, and Factory. As Thatcher’s economic policies emptied the city’s factories of jobs, that do-it-yourself punk ethic reigned supreme.

The Smiths broke big: true outsiders tasting mainstream success. A slew of bands white and black did their own thing. Experimental dance outfits like Biting Tongues, Broken Glass, Quango Quango, Dislocation Dance and more labels, Playhard, Playtime, Bop, Ugly Man, In-Tape. All of them successful in that indie sphere, whether putting out jangly guitar tunes or dance tunes.

Every year there was another band tipped for the top that fell by the wayside: James, 52nd Street, The Railway Children, Easterhouse, The Chameleons and Yargo.

In the wings were The Happy Mondays, The Inspiral Carpets, who just seemed to power through with an edgy determination, and some great hip hop including MC Buzz B, the so-called Morrissey of rap, The Ruthless Rap Assassins, A Guy called Gerald, and MC Tunes – all championed by Radio One DJ John Peel and all given their start along with 808 State by local DJ and producer Johnny Jay, a figure as important and influential in so many ways to the Manchester music scene as the late Tony Wilson.

The scene was burgeoning and healthy, black and white. But in 1989, it was still New Order and especially Simply Red who were selling all the records.

The unlikeliest band to succeed, The Stone Roses, had the most devout followers – 15-22 year old Mancunians, forged from the warehouse parties of the mid 80s where any minor could get in with a ticket and drink beer all night.

The Stone Roses had to do the warehouse parties concocted by Steve Adge, their tour manager of 30 years and counting, because they couldn’t get gigs anywhere. They’d tied in with Howard Jones and Lindsay Reade, the ex-wife of Tony Wilson, so were more or less blackballed media-wise and gig-wise in Manchester.

To exacerbate things further, they then went and sprayed graffiti with their band’s name on every monument around Manchester, which pushed them even further out on the fringes.

Their debut single didn’t reflect how good they were live and by the time their second single, Sally Cinnamon, came out almost two years later, it was almost like they’d refused to curl up and die.

Any other band facing what The Stone Roses faced in their home town would have packed it in but, as the old saying goes, when the going gets weird the weird turn pro.

So The Stone Roses accepted the peculiar management style of Gareth Evans and became the resident band at the International 2 in Manchester and the word of mouth and the love of the kids just grew and grew.

By the time Made Of Stone was released as a single in early 1989, it was plain that everyone else was in their wake.

They’d been knocking about since 1984 and had always exuded a fierce ambition and determination on stage. It was like, “they’re good but who do they think they are?”

That arrogance and swagger marked them out and made them relatable to that generation of youth training scheme kids who, like the band themselves, believed they deserved better.

The Stone Roses were permanent outsiders in Manchester. No John Peel sessions, no love-in with the music press.

By the time Tony Wilson realised how good they were courtesy of The Happy Mondays playing him their records, it was too late for Factory.

Like The Smiths six years earlier, they’d missed out on a phenomenon. Factory needed to be seen to be at the centre of this huge Mancunian bubble of talent but had failed again.

In early 1989, Factory had only signed a folk rock band, To Hell With Burgundy, a classical roster and a busker, Rob Grey, to their label and looked out of touch despite the fact that they had The Hacienda club making waves nationally.

It wasn’t long after the fact that most of the Manchester bands were getting free flares and hoodies off Joe Bloggs and their fans were wearing them that Tony Wilson came in and described the phenomenon and the fashion:

“It’s ‘Madchester’ and it’s about kids wearing baggy clothes who like the Happy Mondays and those other bands and go to the Hacienda, it’s an indie-dance crossover thing”.

To me as a local radio presenter who’d won two Sony Awards for best specialist music show playing all the Manchester tunes on my nightly show on Piccadilly/Key 103, Madchester looked like Factory tagging The Happy Mondays onto the Stone Roses coat tails and giving the Hacienda an undeserved prominence at the centre of a scene it was a part of but hardly essential to.

So Madchester became all about white indie bands trying to play their version of pop music whose fans also liked house and dance music and went to the Hacienda rather than the other thirty clubs playing similar music.

The fact that it left Moss Side’s Ruthless Rap Assassins, MC Buzz B, Chapter & The Verse and other artists outside the gang, despite their music being much more likely to be heard at the Hacienda, was ultimately to its detriment.

Despite fantastic sales and sell out tours for Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets, James, 808 State and The Charlatans, it was The Stone Roses who bestrode the whole scene like a colossus.

Every gig was an event. Every sound bite a provocation. A band scorned for the best part of five years because they didn’t quite fit in.

Their eventual success seemed to be shared by their fans. Eccentric management, spattering their record companies offices with paint, arrogance and pointless belligerence reflected a youthful passion and integrity.

Manchester’s music scene from 1988-1990 was fresh and was a time of positivity bursting with bands who would all become overnight successes that were 5,6,and 7 years in the making, with great merchandising and t-shirts.

It’s when Manchester realised that it could exist outside the mainstream – and that mainstream still hates Manchester for the way it has achieved Tony Wilson’s ambition.

30 years after the release of that Stone Roses debut, kids still know their name and worldwide TV audiences see Manchester United step out onto that Old Trafford pitch to the The Stone Roses song This Is The One and hear United fans singing Ole’s At The Wheel to the tune of The Stone Roses’ Waterfall.

Two songs bigger than the band themselves from one album that changed things forever. Happy 30th birthday. This is Manchester. We do what we want.

- This article was last updated 6 years ago.

- It was first published on 26 April 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Manchester BMX club puts the wheels in motion to help a local hero

Celebrating the amazing people taking on Great Manchester Run in 2025

Frankie Lipman steps into Lady Macbeth’s shoes in gutsy new take on Shakespeare

Best bars and pubs to watch the football and live sport in Manchester