Book review: Boy Number 26 – Tommy Rhattigan’s harrowing tale of a child in “care”

- Written by Ray King

- Last updated 6 years ago

- Books, Culture

If you think the worst thing that could happen to a seven-year-old boy was to be lured into a house by Myra Hindley on the promise of a slice of bread and jam, think again.

For little Tommy Rhattigan, it did get worse. A whole lot worse.

While Tommy was able to escape the clutches of Hindley and her co-monster in crime Ian Brady through a window in her grandmother’s house in Gorton, escaping the tormentors working in the state’s so-called care system was another thing altogether. In fact it was impossible.

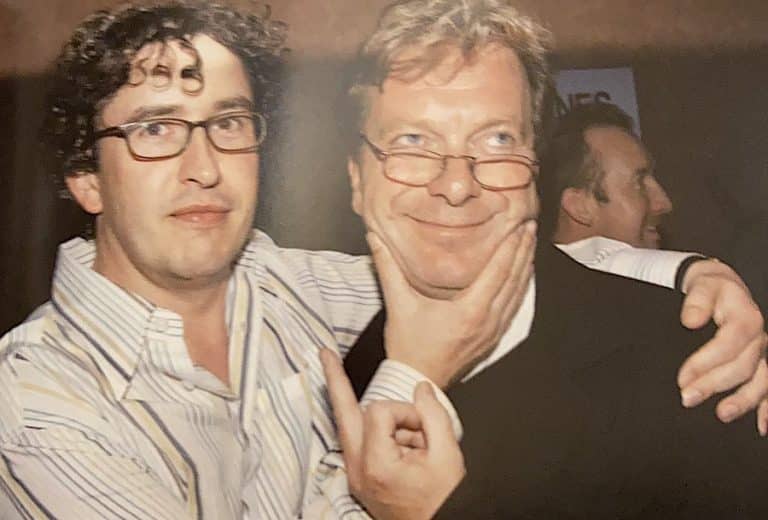

When I interviewed Tommy after 1963: A Slice of Bread and Jam – his first book describing his life as a child in a Hulme slum with an alcoholic and abusive father and negligent mother – he said it had been the happiest time of his life.

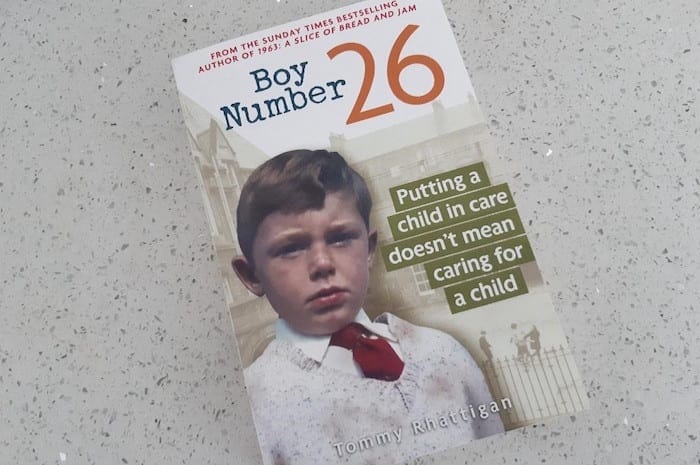

By contrast, the years that followed, the subject of his just-published sequel Boy Number 26 (Mirror Books, £7.99) proved to be the worst of times.

A persistent truant, he was placed in the care of the local authority ay the age of eight and spent time in children’s homes and later in approved schools.

“They put me in a care home because I refused to go to school. I wanted the freedom of roaming the streets. It was all I knew.”

Falling foul of paedophiles in the care system, he said: “I was abused for years. It was the worst period of my life – absolutely horrendous. They took my soul. When you mature into a man – that’s when the events of childhood have their biggest effects.

“I suffered with mental health issues because of the guilt you carry. You blame yourself for what has happened to you. It doesn’t just make you a lesser man but a lesser human being.”

He was moved from a children’s home in Manchester to the notorious St Vincent’s Approved School in Formby, Liverpool, where he was subjected to a regime of almost daily horrific abuse.

As with the first book, readers have, of necessity, to afford Tommy a considerable degree of author’s licence, for the detail with he recounts the episodes of relentless cruelty to the extent of recalling conversations – in quotes – is quite remarkable for someone who was under ten years old at the time.

Yet memoirs of abuse, victimhood and misery have, down the years, proved to be a much more successful literary genre than books about tiptoeing happily through the tulips, and Tommy lays it on with a very big trowel.

In fact, were in not for his remarkable ability to inject some humour into his narrative, it might be all too easy for readers to suffer sympathy fatigue.

But in the end, Tommy survives – and is given the opportunity to effect at least a modicum of justice following the arrival “out of the blue” of a letter from the Chief Constable of Merseyside inviting him to assist the police with their inquiries into allegations surrounding St Vincent’s.

He describes agonising for weeks before finally picking up the telephone, then: “At the precise moment I placed the receiver back down I felt a heavy burden fall from my shoulders…

“I knew my new life was about to begin.”

- This article was last updated 6 years ago.

- It was first published on 18 March 2019 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Hilton Manchester Deansgate’s superstar chefs shine on the world stage

Stalybridge to get multi-million pound makeover of public spaces

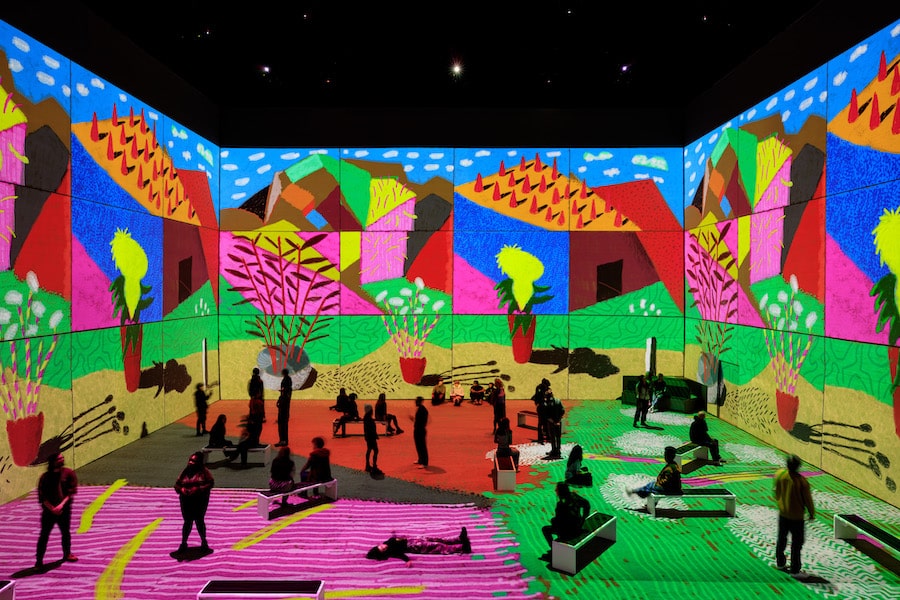

Review: The Engagement Party at Queen Elizabeth Hall ‘is full of immersive fun’

Piehard: where to get the best pies in and around Manchester