The unsung activist who transformed LGBTQ+ rights in the UK

- Written by Thom Bamford

- Last updated 8 months ago

- City of Manchester, Featured, History, LGBT+

The history of LGBTQ+ rights in the United Kingdom is marked by the courageous efforts of individuals who dared to challenge the status quo.

Among these pioneers, one name stands out for its lasting impact on the legal and social landscape of the country: Alan Horsfall.

Working from Greater Manchester, he was a key figure in the campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in England.

It could be argued that Alan Horsfall’s contributions laid the foundation for the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement.

His life was defined by a relentless pursuit of equality, even when faced with significant personal and political risks.

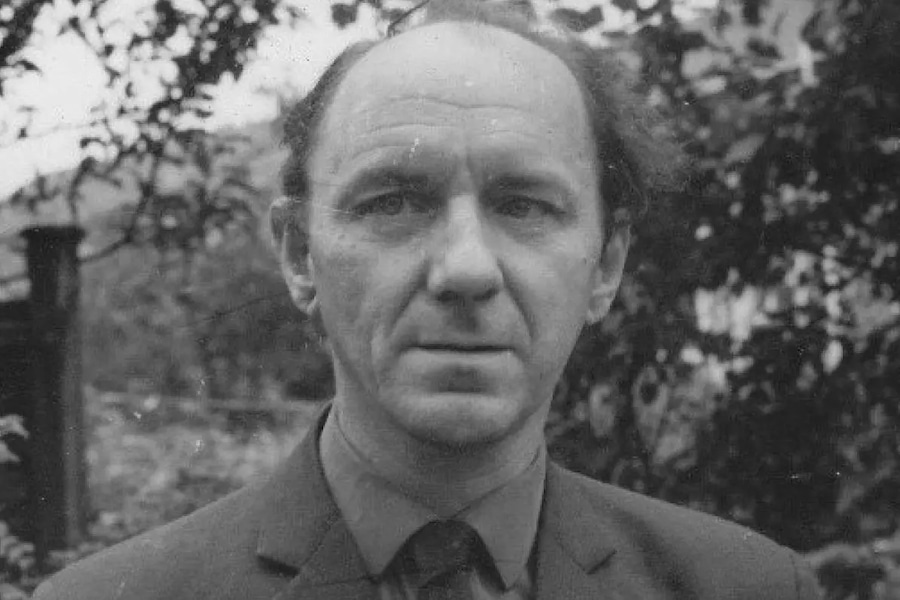

Alan Horsfall

Early life

Born in 1927 in the small Lancashire village of Laneshaw Bridge, Alan Horsfall was raised by his grandparents in a traditional, conservative household.

His early years were spent in the heart of rural England, on the edge of the Yorkshire Moors, far removed from the diverse cities where LGBTQ+ subcultures were beginning to take shape.

This conservative upbringing, however, did not define Horsfall’s views.

Instead, it was his experiences during his service in the Royal Air Force (RAF) after World War II that began to shape his understanding of his own identity and the challenges faced by gay men in Britain.

During his three years in the RAF, Horsfall met other gay men, including his life partner, Harold Pollard, a primary school teacher.

This relationship became a central part of Horsfall’s life, providing him with the emotional support needed to undertake the challenges ahead.

After leaving the RAF, Horsfall returned to Lancashire rather than seeking the anonymity of a city.

He found work as a clerk for the National Coal Board, but his life in a small-town mining community was marked by the secretive and often repressive atmosphere surrounding homosexuality at the time.

He later worked for the Salford education committee.

The Fight for Legal Reform

Horsfall’s political awakening came during the Suez Crisis in 1956, an event that radicalised many of his generation.

He joined the Labour Party and soon became an active member, driven by a desire to address social injustices, including those faced by homosexuals.

However, within the Labour Party, Horsfall encountered significant resistance. Many members believed that homosexuality was not an issue for the working class, reflecting the broader societal prejudice of the time.

Despite these challenges, Horsfall became involved with the London-based Homosexual Law Reform Society in 1958, a group dedicated to advocating for the implementation of the recommendations of the Wolfenden Report.

Published in 1957, the report was a groundbreaking document that recommended the decriminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults in private.

However, turning these recommendations into law was far from straightforward.

Horsfall found himself increasingly frustrated with the London-centric focus of the Homosexual Law Reform Society and the lack of involvement from supporters outside the capital.

The North West Committee for Homosexual Law Reform

Undeterred, Horsfall took matters into his own hands. In 1964, he co-founded the North West Committee for Homosexual Law Reform, based out of his miner’s cottage in Atherton, Greater Manchester.

They had their first public meeting in Church House, Manchester, on 7 October 1964.

Allan supported the Homosexual Law Reform Society (HLRS) from its inception in 1958, but was frustrated at the lack of involvement of supporters – never members – especially outside London.

After several years spent overcoming deep reluctance within the London organisation, he got the blessing of General Secretary Antony Grey to start what was intended to be a compliant satellite, lobbying Northern MPs.

Allan’s decision to use his personal address and phone number, which in its time was an act of considerable bravery, was deliberate.

There were several Labour MPs in industrial constituencies who opposed decriminalisation because ‘the miners would not stand for it.’

Allan Horsfall proved it was possible to run a Law Reform campaign from within a mining community without the sky falling in.

However, there was some personal cost in the reaction of the local gay community.

He was shunned in the bars by people who feared he would bring the police down on them.

His partner was warned that he should not be seen in public with Allan. They both ignored this.

This act of establishing the committee in a working-class, industrial area was both bold and dangerous.

Horsfall used his own home address as the contact point for the organisation, a decision that exposed him and his partner to potential hostility and persecution.

It was a move that demonstrated Horsfall’s deep commitment to the cause and his belief that gay men and lesbians should not have to conceal their identities to fight for their rights.

Decriminalisation and beyond

The North West Committee for Homosexual Law Reform, evolved into the Campaign for Homosexual Equality in 1971.

At its height, CHE boasted over 130 local groups and more than 5,000 members.

It was the most successful attempt in this country to create a mass-membership democratic LGBT organisation.

If its legislative gains were small, it changed the lives of thousands of individuals through its groups, encouraging self-respect through “coming out”.

The tireless campaigning of Horsfall and others eventually bore fruit with the passing of the Sexual Offences Act in 1967, which decriminalised homosexual acts between consenting adults in private.

This legal reform was a watershed moment in British history, but Horsfall understood that changing the law was just the beginning.

The stigma and social prejudices that surrounded homosexuality were deeply entrenched, and much work remained to be done to achieve true equality.

Following the legal victory, Horsfall played a pivotal role in transforming the North West Committee for Homosexual Law Reform into the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) in 1971.

You can find out more about the organisation by clicking here

CHE became the first successful large-scale, member-driven LGBT organisation in Britain, with over 130 local groups and a membership exceeding 5,000 at its peak.

Under Alan Horsfall’s leadership, CHE not only advocated for further legal reforms but also focused on building a sense of community and solidarity among LGBT individuals across the country.

Esquire Clubs

One of Horsfall’s most innovative ideas was the creation of Esquire Clubs, social spaces modelled on working men’s clubs that would provide LGBTQ+ individuals with a safe environment for socialising and cultural activities.

These clubs were envisioned as member-owned spaces that could foster a sense of belonging and self-respect.

However, the social climate of the time made this vision difficult to realise.

Many feared that joining such a club would effectively “out” them, and in several locations, local authorities refused to grant licences.

Despite these setbacks, the idea of Esquire Clubs highlighted Horsfall’s understanding of the need for both legal and social change.

Legacy and later Yyars

As the 1970s progressed, Horsfall’s health began to decline, following a severe heart attack in 1970.

He gradually stepped back from the front lines of activism, though he remained involved in the movement.

In 1974, he was named President for Life of CHE, a testament to the respect and admiration he had earned within the LGBT community.

Even as he took a less active role, Horsfall continued to influence the direction of the movement through his advice and guidance.

In his later years, Horsfall remained a vocal advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and other social causes.

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

He was an active member of his local Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) group and regularly contributed letters to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent.

Those who knew him during this period describe him as a gentleman, a man of quiet dignity and unwavering principles.

Alan Horsfall’s life was marked by both personal and public challenges, but his contributions to the LGBT rights movement in Britain are immeasurable.

His decision to live openly as a gay man in a small, conservative community, his dedication to legal reform, and his efforts to build a national LGBT organisation have left a lasting legacy.

He is remembered as a man of integrity, courage, and vision—a true pioneer whose work helped to lay the foundations for the freedoms that LGBT individuals enjoy in Britain today.

When Allan Horsfall passed away in 2012 at the age of 84, the LGBT community lost one of its founding fathers.

His story serves as a reminder of the progress that has been made, and of the work that remains to be done.

- This article was last updated 8 months ago.

- It was first published on 12 August 2024 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Now you can own a piece of TV history and support a much loved NHS Charity

The welcoming Manchester community where board games build friendships

Everything you need to know about the St George’s Day Parade 2025

Best bars and pubs to watch the football and live sport in Manchester

Discotheque Royale vs Piccadilly 21s: which was your favourite 90s Manchester club?