This national treasure on your doorstep gives a fascinating insight into Manchester’s history

- Written by Louise Rhind-Tutt

- Last updated 8 years ago

- City of Manchester, Culture

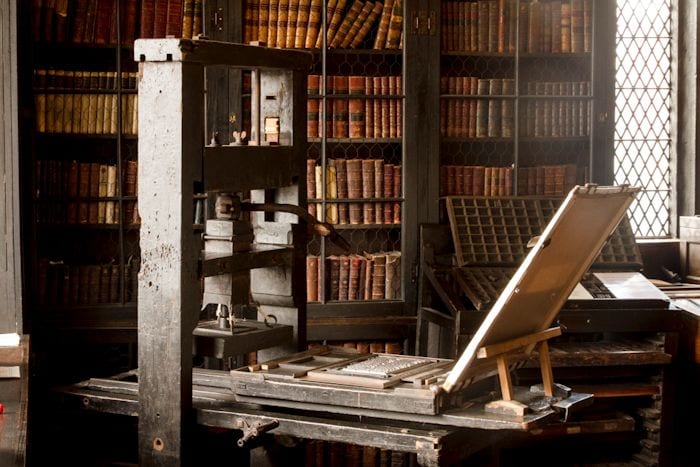

Britain’s oldest surviving public library, Chetham’s, was founded in 1653 and has been in continuous use as a free public library for over 350 years.

The beautiful sandstone building dating from 1421 was built to accommodate the priests of Manchester’s Collegiate Church and is part of the oldest complete structure in the city.

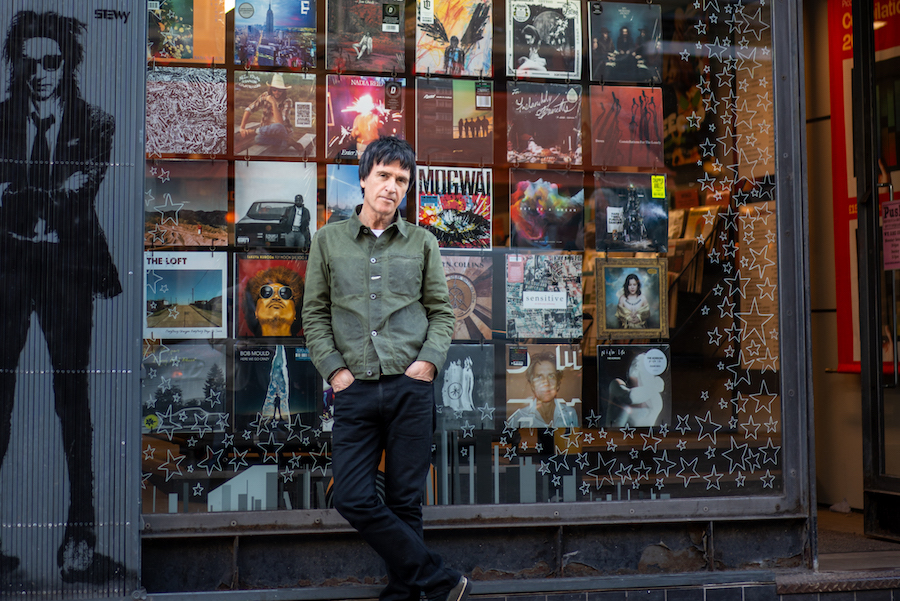

You could easily walk past this national treasure, tucked away next to the famous School of Music in the shadow of the National Football Museum and Manchester Cathedral, but the library is open to the public and is well worth a visit.

GESTURED, a new installation of artworks based on notes and scribbled drawings by Elizabethan alchemist John Dee, celebrates the past and future of the historic building, incorporating digital 3D scanning and printing alongside traditional scientific and hot blown glass.

John Dee (1527–1609) was an alchemist, polymath and advisor to Elizabeth I. As warden of the Manchester Collegiate Church, Dee lived in Chetham’s School but was forced to leave the city in disgrace in 1603 for allegedly summoning the devil.

A table bearing a circular burn mark allegedly made by Satan’s hoof still exists in the library’s Audit Room.

“Notes and drawings by 16th century alchemist John Dee, including sketches of apparatus for his experiments, and drawings of gesturing hands, were the starting point for the new pieces of work created for this installation and lead the audience on a very personal itinerary through the library collection,” says Chara Lewis from Brass Art, the group behind GESTURED.

“Chetham’s Library staff have revealed the fascinating books and illustrations in the collection, and shared their expertise on gestures and symbolism.”

Working with experts from Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester University, Edinburgh College of Art and University of Huddersfield, Brass Art have translated gestures found in prints, marginalia and book illustration into new sculptural forms using traditional casting and 3D printing processes.

“The mysterious transformation of materials which fascinated Elizabethan alchemists has also inspired our work, and we hope that people who see the installation will be drawn into the history and atmosphere of the library,” says Lewis.

The library itself gives a fascinating insight into Manchester’s history. After the Reformation, the premises were purchased through the will of local merchant Humphrey Chetham in 1653, whose ambition to overcome poverty by curing ignorance had led to him setting up a charity school to pay for the education of boys from the Manchester region.

Chetham’s governors purchased the medieval College House, and the Library was housed on the first floor to avoid rising damp.

It is interesting to note that the money Chetham left in his will for books was worth twice as much as the building itself – £1000 and £500 respectively – demonstrating the value of knowledge at that time.

In accordance with Humphrey Chetham’s instructions, newly acquired books were chained to the bookcases – a practice abandoned in the mid eighteenth-century and replaced by the gates you see today.

The library soon built a collection to meet the needs of the clergy, lawyers and doctors of Manchester and surrounding towns, and books were arranged on the bookcases according to size rather than any particular order.

The first proper catalogue wasn’t published until 1791, and that was in Latin. These days visitors can search the catalogue online.

As well as early printed books, the collections at Chetham’s range from illuminated manuscripts made for royalty through to documents which record the minutiae of everyday life such as letters, diaries and account books.

Forty-one medieval manuscripts include the thirteenth-century Flores Historiarum of Matthew Paris – a chronicle of world and English history – and a fifteenth-century Aulus Gellius bound for Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary.

The literature collection at the library contains Greek and Latin classics including the first printing of Homer (1488) and Plutarch’s Lives (1517), in addition to rare first editions of key works such as Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) and Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667).

The collections are of international significance, but Chetham’s is also a library specialising in Manchester. They continue to collect books and documents about the city, and the library boasts extensive Belle Vue Collections stretching from the mid-1800s through to its final days in the 1970s as well as a collection of Northern Soul paraphernalia.

In addition to modern titles, you’ll find the oldest history of Manchester – Richard Hollingworth’s 1656 autograph of Mancuniensis – as well as the first ever census of Manchester, compiled in 1773–74.

The Manchester Scrapbook, compiled by the Earl of Ellesmere and donated to the Library in 1838, contains almost 400 items including pen-and-ink sketches of local characters, scenes and customs by Manchester antiquarian and saddle-maker Thomas Barritt and artist Daniel Orme.

Chetham’s Library was also the meeting place of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels when Marx visited Manchester in the summer of 1845, and the desk by the window in the Reading Room – which you can still sit at today – is where they famously began their work on the Communist Manifesto.

Sue McLoughlin, heritage manager at Chetham’s Library, feels that the new artworks perfectly capture the library’s enchanting atmosphere and history.

“Brass Art immediately understood the magic and atmosphere of the library space, and they have responded by producing work with a mysterious, multi-layered quality,” says McLoughlin.

“The artworks will be positioned around the library in unexpected locations and seldom-seen spaces, enticing people to explore and discover different parts of the building, which dates back to the 1400s.”

GESTURED will be on show at Chetham’s Library from 13 October to 8 December 2017. Admission is free.

- This article was last updated 8 years ago.

- It was first published on 28 September 2017 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Review: Tambo & Bones at HOME is ‘ambitious, bold, gutsy…. and terrific’

Review: JB Shorts 26 at 53two is ‘a five-star showcase of northern talent’