Review: new Morrissey biopic England is Mine – a film buff’s view

- Written by Elliot Garlick

- Last updated 8 years ago

- Cinema, City of Manchester

For anyone choosing to watch England is Mine, the unofficial Morrissey biopic released yesterday, one thing will quickly become evident. It’s less like one complete film and more two separate pieces.

Note how I said pieces and not halves. The first hour or so of the film, an undeniably courageous attempt to tell the early story of the Manchester music legend, is technically proficient but drearily written, using overly-clever dialogue to trick the audience into thinking that the character portrayed as Morrissey holds a level of genius unattainable to mere mortals.

While this may be the case in real life, I’ve yet to meet the person, no matter how clever, who is willing to compete in classical spoken poetry battles without also being an insufferable human being – something that the cinematic Morrissey does every few scenes.

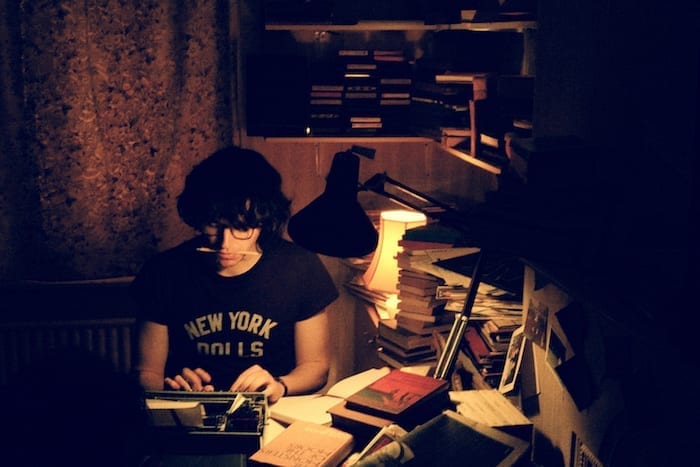

England is Mine also seems to take place in an entirely alternative universe where being a shy, socially inept kid who reads too much is instantly irresistible to women. This character – presented earlier with almost no redeeming characteristics – has no fewer than three female suitors. This is not necessarily a criticism. In fact, I want that universe to be real, because I’d move there immediately.

Director Mark Gill has won a Bafta, was nominated for an Oscar and was a genuinely great guy when I met him recently. His clear skill as a film maker and communicator should make him a very good director, but two-thirds of the opening run time feels like watching an emotionless, heroin-free adaptation of Trainspotting.

It’s well made – despite the Dutch angles appearing too pronounced in some shots – but ultimately feels flat, only saved from being generic by a joke actually landing every once in a while.

After Morrissey’s first attempt to break the industry fails, the second piece of the film falls into place. The tone shifts, the scenes become bleaker, the dialogue develops and we see a believable entrance for the real Morrissey, a bitter, sardonic, angry youth who would one day inspire rebellion in the hearts of teenagers everywhere.

In short, this is the Morrissey audiences were waiting to see. Even the visuals become more engaging, taking risks with colour and texture in a way that the first hour did not, adding water droplets and reflections in a way that is both aesthetic and deeply emotional.

Especially striking is the scene of Morrissey walking along the railroads. The focus on the shale and steel, combined with the blurry figure walking towards us, is fantastically troubling in a way that few scenes are allowed to be.

It’s a shame, then, that it only lasted twenty minutes. As if almost intentional, the character’s upward journey to recovery parallels the films downward trajectory into mediocrity, implying that Gill and co-writer William Thacker are unable to write convincingly unless their characters are trapped in an inescapable downward spiral.

Considering that Morrissey’s career went uphill from there, I doubt we’ll see a sequel.

After watching England is Mine I was unsure if I liked it, and I’m still debating it now. I certainly enjoyed the experience, but it doesn’t feel like something anyone other than die-hard fans of The Smiths would be in a rush to revisit.

The real film is bittersweet and sad, packed inside a protective layer of competent blandness that is sure to fade from memory with time.

- This article was last updated 8 years ago.

- It was first published on 5 August 2017 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

LOWRY’s Quays Theatre gets a plush new look thanks to award

What is the legacy of Manchester’s most controversial (and maybe best) novel?

Big Issue, bigger heart: Manchester comes together for Colin