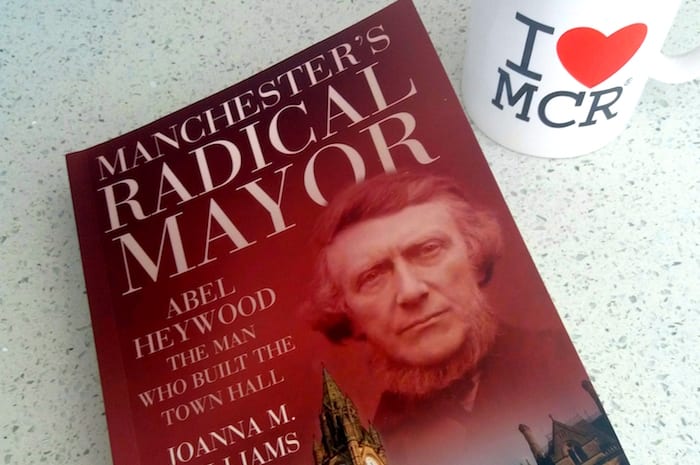

MancBook Review: Manchester’s Radical Mayor by Joanna M Williams

- Written by Ray King

- Last updated 7 years ago

- Books, City of Manchester, People

On 22nd August 1893, the Great Abel bell in Manchester’s new town hall – inaugurated just short of 16 years before – tolled solemnly and the police band in front of the Albert Memorial struck up Handel’s Dead March.

As flags flew at half-mast and the Lord Mayor and worthies lined up in the square, crowds gathered to watch a cortège pass through the working class streets of Ancoats and Bradford. My grandmother, a girl of 15 at the time, might well have been amongst them.

Abel Heywood who, as a radical politician, Chartist, and tireless campaigner for a free press, workers’ rights and universal suffrage – including votes for women – helped shape the very character of Manchester, was buried with his two late wives in Philips Park Cemetery.

It is a fitting resting place, though his grave is modest by late Victorian standards, for he had been a prime mover in the opening of Philips Park and Queen’s Park, Harpurhey – among the first municipal parks in the country – in 1846.

Today Abel Heywood is best known as “the man who built the town hall.” That’s the subtitle of Joanna M Williams’ meticulously researched portrait. It’s not just a biography, but a detailed story of how Manchester came to play such a major role in the huge social and political changes of the 19th Century.

But if Heywood’s political career, from jail cell to Lord Mayor in 30 years – and elevation to his most cherished honour, Freeman of the City towards the end of his life – was remarkable, his personal journey was astonishing. It took him from one of the city’s worst slums to a mansion in Bowdon, Cheshire, and from abject poverty to what would be, in today’s money, millionaire status.

As the population of Manchester surged with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, Heywood’s widowed mother Betty brought her four children from what was then “the pretty village of Prestwich” in the hope of finding work.

The year was 1819 – one of the most significant in Manchester’s history because of the Peterloo Massacre – though Williams observes that Heywood, aged nine at the time, made little of the co-incidence later in life.

They settled in Angel Meadow and shared a back-to-back house in an area where “not a street or passage…was paved or sewered” and was notorious for crime, vice, overcrowding and disease.

Already literate when he arrived in Manchester, Williams speculates that young Heywood attended Bennett Street Sunday School before finding work in a warehouse in High Street and continuing his education from the age of 15 at the newly founded Mechanics Institution.

By 1830 he was writing and publishing self-improvement essays and had been offered the agency of the radical Poor Man’s Guardian. It was a seminal moment in Heywood’s life, for in 1832 – the year of the Great Reform Act – he was jailed for selling the journal for a penny without paying the fourpence newspaper stamp tax. Unable to pay a £48 fine, he spent six months in New Bailey Prison, Salford.

The sentence entrenched his desire for a free press. Later he wrote: “My incarceration failed to convince me that I was not engaged in a glorious work…”

In the 1840s Heywood gained national notoriety, not only as a Chartist leader but also as the biggest wholesaler of radical publications in the north. His dual career as both politician and successful businessman was born, the latter through printing and publishing in what’s now the Northern Quarter.

In 1847 his firm began printing wallpaper and as early as 1850 he began to branch out into other areas of manufacture and take on financial directorships.

As the political and social tide changed, Heywood called himself a “radical Liberal” – liberal enough to join the Corn Law repealers, radical enough to name his second son George Washington.

His political career saw him become Manchester councillor in 1843 and alderman ten years later. Heywood was twice mayor, but his two attempts to enter Parliament as a Liberal MP for Manchester met with defeat. Williams speculates that his radical beliefs and aggressive debating style had made him enemies.

Her conclusion is that the Great Abel bell, inscribed with Tennyson’s words “ring out the false, ring in the true”, would have delighted him.

Though the book’s style is somewhat academic – not surprising given Williams undergraduate and post graduate studies at the University of Manchester and her later teaching career – her first biography offers an absorbing insight into the man and his times.

Manchester’s Radical Mayor: Abel Heywood – The Man who Built the Town Hall by Joanna M Williams is published by the History Press, £14.99

- This article was last updated 7 years ago.

- It was first published on 26 September 2017 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

Love, loss and the last days of humanity – why ‘A Pineapple’ is a must-see play

Remembering the Busby babes we tragically lost in the Munich Air Disaster

Review: Here You Come Again at Palace Theatre ‘is a rhinestone-studded Dolly delight’

Breaking the Silence – the charity addressing mental health in Manchester’s seniors