All the best pictures from Manchester Pride through the years

- Written by Georgina Pellant

- Last updated 5 years ago

- Events, LGBT+

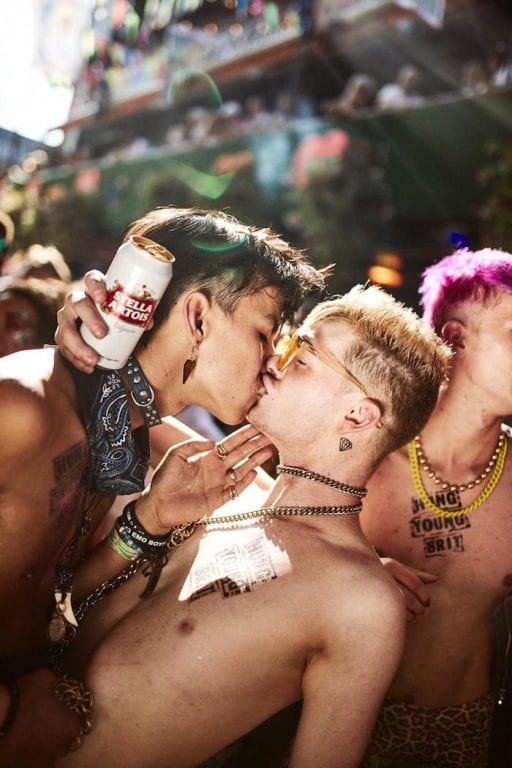

Every August bank holiday weekend Manchester dolls itself up ready for a big Pride weekend.

Rainbow flags line its streets and shopfronts, signs shout “love is love” from every corner and glitter is lacquered on with abundance as the city gets ready for its annual four-day blowout.

Sadly, this year it won’t be taking place due to safety concerns around Covid-19. Events have been moved online, and GMP has announced a ban on drinking in city-centre public spaces this weekend, putting a dampener on any impromptu partying in the park.

But instead of lamenting what can’t be, we thought we’d take a trip down memory lane and look at some of the festival’s best pictures from over the years to cheer ourselves up.

Today the Manchester Pride festival is one of the city’s biggest calendar events of the year, attracting people in their tens of thousands from all over the globe.

Its parade is always one of the weekend’s highlights, filling Manchester’s streets with colour as the city marches and protests for LGBTQ+ equality.

A gorgeous display of style and glamour, it’s also a reminder of the social progress that has been made by campaigners (and that which still needs to come, as exemplified by last year’s ‘march for peace’).

The festival has grown exponentially over the past thirty five years: helping to raise awareness, acceptance and large sums of money for important LGBTQ+ causes as well as cementing Manchester’s reputation as a gay capital.

But when it first began in 1985, it was quite a small affair and organisers had to deal with a lot of hostility from both the police and the public.

Billed as the Manchester Gay Pub and Club Olympics, the first August Bank Holiday celebration in 1985 featured boat racing down the canal, tugs of war and egg and spoon races judged by local drag queens.

At this time, the village was a secretive area which people visited covertly. The community there struggled with a lot of prejudice as well as police raids to stop what was termed ‘licentious dancing.’

Throughout the 80s things slowly began to improve, thanks in part to a new generation of Labour councillors elected in 1984 who put their arms around the gay community and gave it their support.

In a move inspired by Ken Livingstone’s early days on the Greater London Council, they created an Equal Opportunities Committee and appointed Lesbian and Gay officers Maggie Turner and Paul Fairweather.

Councillors also donated £1,700 towards the first pride event (complete with a huge banner on Oxford St), which saw bars get together to fundraise for AIDS organisations in the city – a key concern at the time.

Paul Fairweather, Manchester’s first Gay officer, covered it for Manchester magazine Mancunian Gay:

“Some of the bars got together to raise money for AIDS organisations in the city. There was a lot of support from the gay community and a lot more hostility from people in the city.

“At the time it was a very small event but people really, really put their heart into it. I think underlying it was beginning of the AIDS epidemic – people were concerned about the future.”

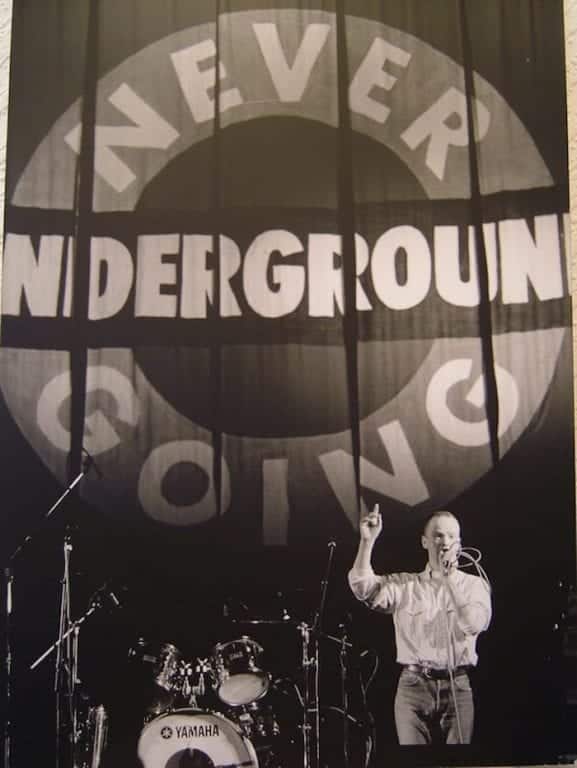

Protests against Thatcher’s Section 28 laws – legislation introduced to explicitly discriminate against gay people – in the late eighties was another turning point.

Just as the LGBT community had started to find its voice, suddenly it feared being pushed underground again. Confronted with the complete unfairness that you wouldn’t be ablt to tell your teacher or social worker if you were gay, protesters both gay and straight flooded to Albert Square in their tens of thousands.

At the time, Manchester was almost alone in opposing the legislation and came under huge pressure both politically and in the media. But ultimately, the rally not only put a stop to Section 28 but also helped bring together different elements of the disparate tribes within the LGBT community.

The early nineties heralded the arrival of the village’s first openly gay bar – a brave move considering that GMP was still raiding its bars as late as 1994.

This period also saw the opening of Nightclub Cruz 101 and the launch of club nights like Electric Chair and Poptastic, culminating with the airing of Queer as Folk – the famous drama series based on Manchester’s gay scene – on Channel 4 in 1999.

Some still called the area Satan’s Square mile and there were still a lot of battles to be won with homophobia still prevalent in the city, but the growing festival really helped put Manchester on the map at a time when gay rights were still under attack.

1991 saw the formation of the Village Charity and the festival was renamed to Manchester Mardi Gras, ‘The Festival of Fun’ raising £15,000 in its first year. By 1997, it had cemented its popularity in the community with people from all different backgrounds. And by the early noughties, it was attracting over 100,000 visitors a year.

1991 saw the formation of the Village Charity and the festival was renamed to Manchester Mardi Gras, ‘The Festival of Fun’ raising £15,000 in its first year. By 1997, it had cemented its popularity in the community with people from all different backgrounds. And by the early noughties, it was attracting over 100,000 visitors a year.

Renamed again from Mardi Gras to Gayfest in 2001, it wasn’t until 2003 the Manchester Pride that we know and love today truly came into fruition with the entire gay village area gated off for the August bank holiday weekend.

What had begun as a few bars fundraising had gradually transformed into a full-on shindig, and it was announced that the event would now be known as Manchester Pride at that year’s final closing ceremony.

In the years that have followed since the event has continued to push the boundaries for LGBTQ+ equality. Manchester’s parade, for example, was the first to include the police, the army and the NHS amongst its floats – a huge step forward when you reflect back on its early (or in fact rather recent) history with GMP.

Yet there is always going to be more to progress to be made – as is proven every year when the question of a straight pride chooses to rear its ugly head. This is just one reason why the community and its allies need to keep coming together, even this year when we cannot stand and march shoulder to shoulder.

Speaking last year chief executive for Manchester Pride Mark Fletcher said: “Every year I am asked do we still need a Pride celebration and every year I say yes we do.”

“We must support every single member of every single LGBTQ+ community and fight until they feel equal and free to be themselves.

“We ask the world to recognise that the fight has only just begun.”

- This article was last updated 5 years ago.

- It was first published on 29 August 2020 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: press@ilovemanchester.com

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to press@ilovemanchester.com

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: advertise@ilovemanchester.com

Manchester BMX club puts the wheels in motion to help a local hero

Celebrating the amazing people taking on Great Manchester Run in 2025

Frankie Lipman steps into Lady Macbeth’s shoes in gutsy new take on Shakespeare

Best bars and pubs to watch the football and live sport in Manchester