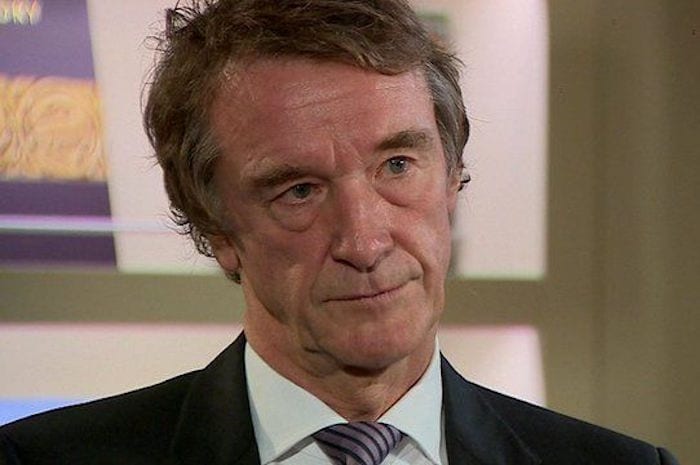

Manchester-born billionaire businessman claims he can cure North-South divide

- Written by Ray King

- Last updated 8 years ago

- Business, Community

Manchester-born billionaire businessman Jim Ratcliffe claims he can “cure” the North-South divide, but for many it will be a bitter pill: fracking.

Ratcliffe, who grew up in a Failsworth council house, is no stranger to controversy. And, by declaring his determination to become the UK’s leading fracker – the method by which natural gas is extracted from deep lying shale rock by pumping down high pressure water – is going to land him in the thick of it.

But the chairman and chief executive of Ineos – one of the world’s leading energy and chemical companies – is adamant that the new source of cheap energy would transform the economic fortunes of the north of England.

Ratcliffe, 64, a billionaire five times over and described as Britain’s most successful post war industrialist, told the Sunday Times magazine recently that he has already set aside £600 million to develop wells and hopes to invest many hundreds of millions more, mainly in the north.

In the he said: “If you go back 20 years, manufacturing in the UK was the same as Germany, about 23-24 per cent of GDP. Germany today is at the same level, but the UK is at 9.2 per cent. We’re at the bottom of the list among major economies. The decline in manufacturing has most severely affected the north of England where I come from….places are not in great shape.”

He argues that acquiring new sources of cheap energy – and there are prospective drilling sites all over Greater Manchester and the north west – would spur investment in manufacturing that the region so badly needs.

Amongst those ranged against Ratcliffe’s ambitions, however are protest groups like Frack Free Manchester, which staged what it claimed was the largest ever anti-fracking gathering in the UK last November.

Bianca Jagger addressed the 2,000 marchers at Castlefield and Andy Burnham, elected Greater Manchester’s executive mayor, declared he could not support fracking anywhere. His stance may prove interesting going forward. Barton Moss has been the scene of confrontations between demonstrators, police and energy company test drillers.

Ratcliffe, however, is dismissive of the environmental concerns voiced by protesters citing America, the most litigious society with the toughest regulations on earth, “where they’ve sunk a million wells and had no really major incidents”.

He told the Sunday Times magazine: “People who are anti-fracking really need to do their homework. They need to be careful they don’t deprive people in the north of England of jobs.”

Fracking in the United States had cut the price of gas by 75 per cent, halved the price of electricity by generating it by burning gas and reduced carbon dioxide emissions my moving away from coal. Energy prices were almost as low as in the Middle East resulting in hundreds of billions of dollars of fresh investment in manufacturing.

The UK had a decent skills base and low corporation taxes, but very expensive energy. Cut the cost and the industries would come.

His vision for post-Brexit Britain – he voted leave – was for the economy to become less fragile, less dependent on services and see less economic power concentrated in the south east.

Ratcliffe, though said to be publicity shy, has been in the headlines recently and is used to getting his way. He fought and won a bitter dispute with the unions at Ineos’s Grangemouth refinery and is determined to build a successor to the no-frills Land Rover Defender.

- This article was last updated 8 years ago.

- It was first published on 19 May 2017 and is subject to be updated from time to time. Please refresh or return to see the latest version.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but many people suffer. I Love Manchester helps raise awareness and funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please support us with what you can so we can continue to spread the love. Thank you in advance!

An email you’ll love. Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news stories delivered direct to your inbox.

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

While we can’t guarantee to publish everything, we will always consider any enquiry or idea that promotes:

- Independent new openings

- Human interest

- Not-for-profit organisations

- Community Interest Companies (CiCs) and projects

- Charities and charitable initiatives

- Affordability and offers saving people over 20%

For anything else, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us about advertorials (from £350+VAT) and advertising opportunities: [email protected]

The very special toy shop where parents don’t pay a penny is open – and busier than ever

Manchester’s oldest homelessness charity celebrates 40 years of supporting the needy

Games, science and history collide at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum this winter

Best bars and pubs to watch the football and live sport in Manchester

How Baguley Hall Primary School is nourishing minds with a morning Magic Breakfast