Did Alan Turing really commit suicide – or was he killed?

- Written by Ray King

- Last updated 10 months ago

- City of Manchester, History

Today (23 June 2023) is the 75th anniversary of the birth of the world’s first stored program digital computer, which was designed and built at The University of Manchester.

On June 21, 1948, shortly after 11am, the Small Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM) – nicknamed The Baby – executed its first program.

But the fate of the mathematics genius who inspired Sir Freddie Williams, Tom Kilburn, Geoff Toothill and the team that built it is still being called into question.

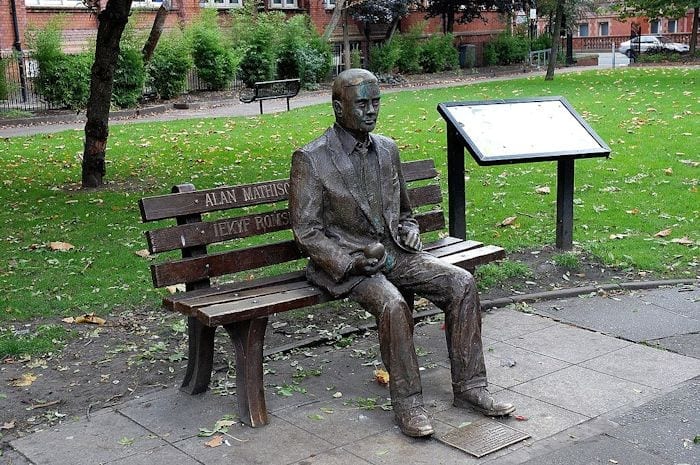

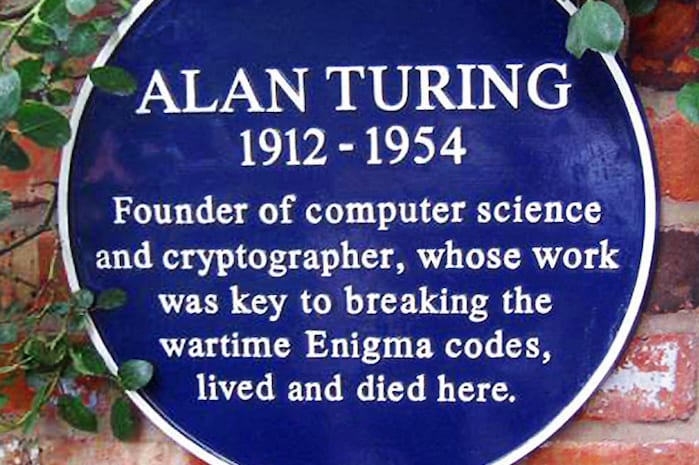

Alan Turing, later hailed for making the biggest single contribution to the Allied victory over Nazi Germany with his code-breaking computing machine, joined the team that same year, his wartime achievements still top secret.

But within six years of the birth of Baby, so called despite its huge dimensions – 17ft long, over 7ft tall and weighing over a ton – Turing was dead, apparently by his own hand, at the age of 48.

Ever since his body was discovered in his Wilmslow home in 1954, questions have been raised about how Turing – a gay man who received scant acknowledgement in his lifetime for his colossal scientific genius – had died with a half-eaten apple by his side.

In 1952, Turing had been prosecuted for gross indecency with a 19-year-old Manchester man after letters were found by police investigating a burglary at his home.

The official coroner’s verdict was suicide. But was it? The late Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw, who worked as a part-time lecturer at the University of Manchester at the same time as Turing, told me she was convinced that he had been murdered – and that other academics shared her view.

Dame Kathleen, who died aged 101 in 2014, offered no evidence, let alone proof. But the possibility that Turing was not just hounded into taking his own life – he had accepted so-called “chemical castration” as an alternative to a prison sentence – but had been actually killed by the security services with an apple poisoned with cyanide, is at least plausible.

Dame Kathleen, who lived in Didsbury, was not alone in believing that Turing was murdered. The gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell demanded in 2013 that a new inquiry into his death should be opened.

In a statement demanding an inquiry, he wrote: “Though there is no evidence that Turing was murdered by state agents, the fact that this possibility has never been investigated is a major failing. The original inquest into his death was inadequate. Although it is said that he died from eating an apple laced with cyanide, the allegedly fatal apple was never tested for cyanide. A new inquiry is long overdue, even if only to dispel any doubts about the true cause of his death.

“Turing was regarded as a high security risk because of his homosexuality and his expert knowledge of code-breaking, advanced mathematics and computer science. At the time of his death, Britain was gripped by a McCarthyite-style anti-homosexual witch-hunt. Gay people were being hounded out of the armed forces and the civil and foreign services.

“In this frenzied homophobic atmosphere, all gay men were regarded as security risks – open to blackmail at a time when homosexuality was illegal and punishable by life imprisonment. Doubts were routinely cast on their loyalty and patriotism. Turing would have fallen under suspicion.”

The author Roger Bristow, founder member of the Bletchley Park Trust and former mayor of nearby Milton Keynes, also cast doubt on the suicide verdict in his book as has Prof Jack Copeland, a New Zealand -based academic and director of the Turing Centre in Zurich.

If Turing’s mind had been in turmoil at the time of his death – though acquaintances maintained he was happy and he left no note – the spooks were in a state of paranoia.

In 1951, senior Foreign Office officials Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess had disappeared, eventually resurfacing in Moscow years later. Burgess was homosexual, at the time an illegal trait that the intelligence services came to regard – not without reason – as being an extreme security risk because of the threat of blackmail.

In 1952, John Vassall had been appointed to the staff of the Naval Attache at the British embassy in Moscow. A homosexual, Vassall fell into a classic honey trap and the Soviets used photographs to blackmail him into working for them as a spy, initially in the Moscow embassy, and later, in June 1956 following his return to London. He worked for the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division providing the Soviets with several thousand classified documents, including information on British radar, torpedoes, and anti-submarine equipment.

Vassall was regarded in intelligence speak as “a low-level functionary” despite the damage he was able to inflict. Turing – though there has never been a scintilla of doubt about his loyalties – would have been seen as an altogether different kettle of fish: a potential blackmail target whose work at Bletchley Park was deemed so vital to national security that it remained secret until well into the 1970s. Was it his knowledge that cost him his life?

The inquest into Turing’s death was perfunctory to say the least. The apple was never tested. It was almost as if the state wanted all the lose ends tied up as speedily as possible. His legacy, however, was just too important and his persecution too harrowing to airbrush from history.

In 2009, then Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official apology on behalf of the government for Turing’s treatment and the Queen later granted him a posthumous pardon. But no-one has offered to delve deeper into the circumstances of Turing’s premature death.

Did we miss something? Let us know: [email protected]

Want to be the first to receive all the latest news stories, what’s on and events from the heart of Manchester? Sign up here.

Manchester is a successful city, but there are many people that suffer. The I Love MCR Foundation helps raise vital funds to help improve the lives and prospects of people and communities across Greater Manchester – and we can’t do it without your help. So please donate or fundraise what you can because investing in your local community to help it thrive can be a massively rewarding experience. Thank you in advance!

Got a story worth sharing?

What’s the story? We are all ears when it comes to positive news and inspiring stories. You can send story ideas to [email protected]

Science and Industry Museum celebrates our brilliant bodies and incredible insides

Manchester Women’s Aid marks 50 years with empowering fundraising appeal

New Aldi and Costa drive-thru is coming to Tameside town

Worker Bee: Meet Katie Zelem, the captain of Manchester United

Worker Bee: Meet Maurizio Cecco, the founder of Salvi’s and Festa Italiana